In the Beginning

Ten thousand years ago, following closely on the heels of the retreating glaciers, a strange looking animal, one that walked on two legs, appeared. Humans had arrived in the Rideau region. Archaeological evidence indicated that humans inhabited the area near present day Perth, on the shores of the ancient Champlain Sea (see Geology) as far back as 9,000 to 8,000 B.C. Evidence of human occupation in the area of Kingston goes back to 7,000 B.C. Although people of that time tended to be pre-occupied with day to day survival, it can be imagined, that, like the present day residents and visitors to the region, they appreciated looking up at the millions of stars visible on a clear Rideau night, hearing the haunting call of the loon, and enjoying the cool evening breezes that blow across the lakes of the region.

Early Humans

These early inhabitants to the region arrived by following the herds of animals that grazed on vegetation that was springing up in the wake of the retreating glaciers. In the sub-arctic climate of the time, these people hunted large mammals such as caribou. Although no evidence has yet been found, it is possible that mastodons roamed this region at that time (they went extinct close to this time period), and these too would have been attractive food sources for early humans. Archaeological evidence for human presence in this area is scant, but two fluted projectile points, dating back to 9,000 to 8,000 B.C., have been found in the Rideau region.

|

Indigenous Dugout Canoe Carving

This has been interpreted to show six people in

a dugout canoe. It was carved onto a fragment

of a slate tool. While it cannot be directly

dated, it was reportedly found with other

archaic period artifacts near Lower Rideau

Lake, making it possibly up to 8,000 years old.

From “Palaeo-Indian and Archaic Occupations

of the Rideau” by Gordon D. Watson, Ontario

Archaeology Vol. 50, 1990. |

Archaeological evidence for the Archaic period (7,000 to 1,000 B.C.) is much more abundant. The people of that time lived near water, which was one of their main means of travel. An archaeological discovery of an image from that time, carved in stone, shows a six-person dug-out canoe.

They hunted a variety of animals, everything from squirrels to moose. They also ate fish and shellfish, and plant food such as lily and cattail roots, wild rice, and a variety of wild berries and fruits. They had a variety of tools to help them in their hunting and food preparation including such things as projectile points, adzes, gouges, knives and hide scrapers.

Their adornments included beads made of copper, stone, and shell. Their proximity to water routes such as Lake Ontario, the St. Lawrence, the Ottawa and the Gatineau rivers, made long distance travel and communication a possibility. The native copper used in beads, spearpoints, fishhooks, awls, axes and other items, most likely came from pit mines on Isle Royal in Lake Superior and the Keweenaw Peninsula in Michigan. Copper was being extracted from this area over 5,000 years ago. The distribution of copper artifacts suggests that the Ottawa River Valley was a major trade route for these materials.

By the start of the Woodland period, about 1,000 B.C., (3,000 years ago), pottery first came into use. The inhabitants located on the shores of the St. Lawrence, Lake Ontario and Georgian Bay still maintained a "hunter-gatherer" lifestyle but were less nomadic than their forebearers. Within the Rideau region however life continued to be nomadic, consisting of seasonal rounds of the region for hunting, fishing and gathering of plant foods.

Native Nations

| |

|

| | Tribal BoundariesThis map shows Algonquin territory in green and Haudenosaunee (then called Iroquois) in red, the boundary on the Rideau at that time (early 1700s) just south of the watershed divide at Newboro.

From: Canada ou Nouvelle France Suivant les Nouvelles Observations by Pieter van der Aa, 1713 (based on an earlier 1703 map by Guillaume De L'Isle) |

Three major native tribal groups made use of the lands of the Rideau region. These were the eastern woodland tribes, the Iroquoian (mostly Onondaga and Mohawk), Algonquian and Mississaugan (Ojibwe). The Algonquian and Mississaugan are part of the Anishinaabe group of culturally related indigenous peoples. The Iroquois, more correctly known as the Haudenosaunee, were a group (confederation) of tribes, not culturally related to the Anishinaabe.

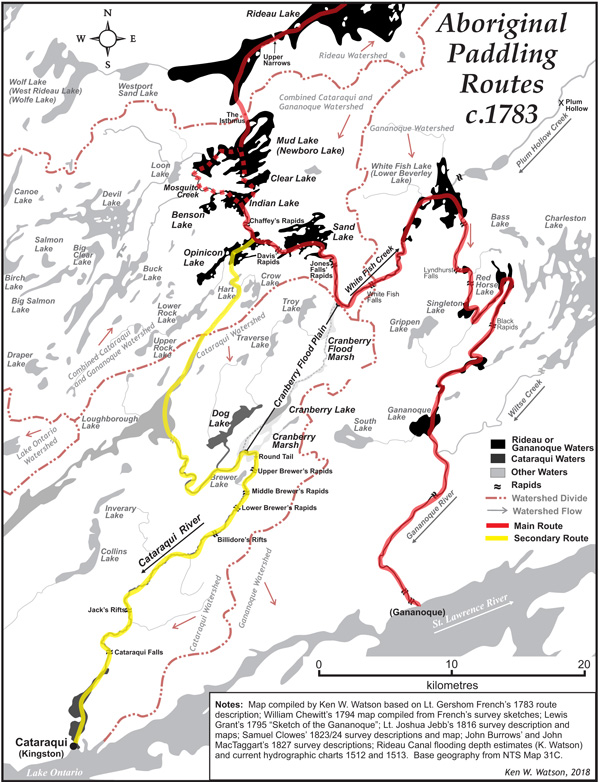

There were no permanent settlements in the Rideau Corridor, indigenous usage was as a travel corridor for trade, the Rideau route connecting the St. Lawrence River with the Ottawa River and as a seasonal hunting and gathering area. The main trade corridor was along the Rideau River to the Rideau Lakes and then down through the Ganananoque system. This was mostly travelled by the Algonquin and Haudenosaunee indigenous groups. The Algonquin, who generally lived on the Upper Ottawa valley region, travelled up the Rideau River into the central lakes area for summer hunting and fishing camps. To the south, the Cataraqui River was used primarily by the Mississisauga peoples to access the inner lakes for fishing and hunting.

By about 1,000 A.D., those living along the shores of the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario achieved a distinct culture, building large palisaded villages and longhouses. They moved to an agricultural lifestyle, growing corn, beans, squash, sunflowers and tobacco. This similarity of culture became known as the Iroquois. Sometime in the 15th century, shortly before Europeans arrived on the scene, villages banded together to form five tribes; the Seneca, Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga, and Mohawk. These tribes joined together in the 16th century to form the League of the Iroquois (or Iroquois Confederacy), also known as the League of Five Nations (later Six Nations when the Tuscarora tribe joined in 1722). Today this group is more correctly known as the Haudenosaunee, meaning "people who build a house" (or "people who lived in a longhouse"), a commonality that links these separate tribes.

It is estimated that at the time of the arrival of the first Europeans, the indigenous population in Ontario was about 60,000 people. It is (unreliably) estimated that the eastern Algonquin population (Ontario and Québec) was in the order of 15,000 and the northern Iroquois population (Ontario, Québec and northern U.S.) was about 80,000. The arrival of the Europeans in the early 1500s brought about huge changes in the native way of life.

Several things happened in the first century after European contact. Many native populations were decimated by European diseases. Old world diseases such as the common cold, measles, influenza, and smallpox became deadly epidemics in native communities. Native populations had no immunity against these diseases, never having been exposed to them before. Fur trapping was introduced and became an economic foundation for the tribes. In order to acquire coveted European-made items (e.g. flintlock muskets, iron axes and knives, brass kettles), native groups started large scale trapping, in conjunction with European trappers, to provide the European market with the furs it wanted.

Trapping led the natives to form allegiances with the major European players of the day, the French and the British. The Algonquin allied themselves with the French, and the Iroquois with the British. It was inevitable that this would lead to conflict, and in the early 1600s a series of hostilities, known as the "Iroquois Wars", broke out. The Iroquois League of Five Nations attacked other native groups and the French. In the 1630s, the Mohawk were raiding Algonquin villages in the Ottawa River Valley, and by 1640 they were attacking French and Algonquin settlements in the St. Lawrence Valley.

In the Rideau region, the natives who ventured north from the St. Lawrence after about 1,000 A.D. were likely the St. Lawrence Iroquois. This group of people had disappeared by about 1580, likely due to a combination of European diseases and war with the Huron. The Five Nations had little influence in the Rideau until about 1660, when they built a series of settlements along the north shore of Lake Ontario. These settlements lasted until the early 1700s when they were taken over by the Ojibwa (Mississauga) invading into this area from the north.

The Iroquois Wars continued throughout the 1600s. These were finally brought to a halt in 1701 when the Iroquois ratified a treaty that committed them to neutrality in the wars between the British and the French. In 1756 the Seven Years War started between the French and the British. After the fall of New France (Québec) to the British in 1760, many Algonquin and Iroquois peoples allied themselves with the British.

During the American Revolution, Iroquois loyalties were split, and many of those in New York state, who sided with the British, later moved to Canada along with the United Empire Loyalists, and settled on land given to them by the British, in Southern Ontario.

As the Indian Reserve system took hold in the late 1700s, many indigenous peoples moved to these communities. Since the Rideau had no traditional permanent native habitation, reserves were never established in this region (many of the new reserves were established along the north shore of Lake Ontario.) The days of the traditional "hunter-gatherer" were drawing to a close.

European Settlement

Ontario, a word which is believed to be derived from the Iroquois word "Skanadario", which means "beautiful water" was first settled by Europeans in the 1600s. The first European to see Ontario may have been Etienne Brulé, who was sent in 1611 by Samuel de Champlain, the great French explorer and cartographer, to live with the Algonquin and Huron Indians and learn about the land they lived in. In 1613, Champlain himself made a journey up the Ottawa River and into the Ottawa River valley. In 1632, Champlain published the first map of Canada showing the Great Lakes.

The first European community in Ontario was Sainte-Marie-aux-Hurons (Ste Marie Among the Hurons), a Jesuit mission, built in 1639, near present-day Midland. In the Rideau region, the first community was Kingston, then known as Cataraqui, established by Count Frontenac in 1673 as a fur trading post and fort (Ft. Cataraqui). Kingston's strategic location eventually turned it into a military garrison, and the more elaborate Fort Frontenac was established. This fort was captured by the British in 1758. However, the area was not settled by the British, that wasn't to happen until 1783.

In 1783, with the need to settle United Empire Loyalists, Frederick Haldimand, governor of Québec (at the time today's Ontario and Québec), initiated the purchase of land from indigenous peoples. A British settlement was established at the former Fort Cataraqui, becoming known as King's Town. In October 1783, the Crawford Purchases were made by Captain William Redford Crawford, encompassing what is now the southern Rideau (to about 50 km north of Lake Ontario) and much of eastern Ontario (rest of the Rideau Corridor). It was a purchase, not a treaty, from the Mississisauga (southern Rideau area) and Onondaga (central & northern Rideau area). Due to the overlapping pattern of indigenous usage, much of this land was also being used by the Algonquin at the time, but they were not included.

Also in the fall of 1783, the Rideau River, Rideau Lakes and the White Fish River and Gananoque Rivers, a traditional indigenous travel route, was surveyed by the British Government (Lieutenant Gershom French) to determine its potential for settlement. The reports from Rideau River and Rideau lakes section were favourable and so it was that in 1784 the first land grants were given to the United Empire Loyalists in the county of Leeds (central Rideau region). Many of these land grants were in the form of certificates of ownership for lots of 100 and 200 acres. Although many Loyalists did settle in the area, the region was so remote and inaccessible at the time, that many others never took up residence on their land. The loyalists who did not occupy the lands given to them hindered settlement for a number of years, since the land ownership were still in their names.

An example is Smiths Falls, located on land originally granted in 1786 to Major Thomas Smyth, a Loyalist, and named after him. Major Smyth did nothing with the land, not even visiting it, and in 1810, mortgaged it to a man in Boston. However payment was apparently never made, and assuming he still owned the land, Smyth, in 1823, over 35 years after the land had been given to him, built a small dam and sawmill at the falls.

Smyth's ownership of the land was contested, and in 1824, Smyth lost a court case held in York (now Toronto). The land was sold at a sheriff's sale in Brockville in 1825 to Charles Jones (who also owned the land near present day Jones Falls lockstation), who in turn sold it (for a tidy profit) to Abel Russell Ward. So, it was Abel Ward in 1826 who was the first to move to the area and actively start to build a settlement. The building of the Rideau Canal greatly expanded the settlement His settlement was first called Wardsville, later changed to Smyths Falls, and then to Smiths Falls. Smiths Falls was incorporated in 1882.

Pre-Canal

As we have seen, Kingston was the first major community in the region. By the late 1700s, several small settlements had sprung up in the Rideau region. Many of these settlements centered around rapids and falls on the Rideau where a water powered mill could be set up and used for the sawing of timber or the grinding of grain. Some of these early settlements became thriving communities, others faded into obscurity.

In 1784, the first mills, a sawmill and a grist mill, were built at Kingston Mills. Built by the government, the "King's Mills" were to serve settlers in the area. The establishment of these mills led to the first settlement along the southern Cataraqui River.

In 1790, Roger Stevens, the first settler on the Rideau River, built a cabin and cleared land on Lot 1 of Montague Township and the adjoining Lot 30 of Marlborough Township on the north shore of the Rideau River. Stevens built the first sawmill in the area at the location of the "Great Falls", what was later to become Merrickville.

In 1793, three Loyalist Burritt brothers, led by Stephen Burritt, established themselves in Marlborough Township and founded the settlement of Burritts Rapids. The first bridge across the Rideau was built here in 1824.

In 1793, Roger Stevens died (drowned) and William Mirick, a millwright from Massachusetts, took over his mill. Mirick moved his family to the area in 1802/03 and in 1804 received title to the land in the area and founded what is today the thriving community of Merrickville.

In 1800, Philemon Wright of Massachusetts, with his brother Thomas and several friends, secured land grants in Hull Township and founded Wright's Town. By the time of the building of the Rideau Canal in the late 1820s, Wright's Town was a thriving community, boasting many impressive stone houses, several mills, a foundry, a 3 storey store-house, a hotel and St. James Anglican church. It was much later, in 1875, that it was incorporated and renamed Hull, after a city in Yorkshire, England.

Perth was originally laid out as a military settlement in 1816 to help protect the inland water route connecting Lake Ontario with the Ottawa River, and to act as an administrative centre for settlers in the region. Its name derived from the source of many of its early settlers, Perth, Scotland. Many of these were military officers on half pay pensions.

The next settlement to be founded was Richmond, which was established as a townsite in 1818 when 400 men from the 99th Regiment of Foot and their families settled down in the region. A few dozen settled in Richmond itself, with the others clearing land and setting up farms in the surrounding region.

When Colonel By arrived in the region to start the construction of the Rideau Canal the first thing he needed was a headquarters and a place to station his men and the contractors' workers. Accordingly, in 1826, By laid out the plans for upper and lower Bytown, located north and south of the proposed route of the Rideau Canal. A thriving community took hold. In 1842 it became the administration centre for the District of Dalhousie (now Carleton County). It was incorporated as a town in 1850; changed its name to Ottawa in 1855 and was formally incorporated as the City of Ottawa; and in 1859 it was chosen by Queen Victoria as the site of Canada's national capital.

Indigenous use of the Rideau Corridor continued through the early settlement period, with hunting, fishing and trapping taking place at traditional harvesting areas, although with lower usage than in the pre-settlement period. Much of the corridor was land granted, but remained mostly unsettled. In 1826, at the start of canal construction, it was a sparsely settled frontier, with scattered settlers and only a few small settlements. As the map below illustrates, outside of the communities mentioned previously, only a few small mills such those at Long Island, Merrickville, Smiths Falls, Chaffey's Rapids, Davis' Rapids, Morton, Upper and Lower Brewer's Rapids, and Cataraqui Falls (Kingston Mills) existed in the region.

|

| Davis Lock, 1840 - watercolour by Thomas Burrowes |

Some of these original mills had to be torn down to make way for the Canal. An example is Davis Mill, a saw mill established by an American settler, William Davis Jr. in about 1820. Mr. Davis' land and mill were bought out by Colonel By in 1829 for the sum of £700 (approx $850,000 today) to allow the installation of the dam and lock. When completed, one of the stone masons who worked on building the lock and dam, John Purcell, became the first Lockmaster. In 1842, in reaction to the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837-38, a small stone fort, which later became the Lockmaster's house was built (known today as a "defensible lockmaster's house"). In 1871, Alfred Forster took over as Lockmaster, and for some time the lock was known as "Foster's Lock". No community ever grew up around Davis Lock and it stands today, a solitary lock, looking much as it did when first opened in 1832.

In other areas, thriving communities did establish themselves. In 1802, the land on which the town of Elgin now sits was granted to Ebenezer Halladay, a United Empire Loyalist. The building of the Rideau Canal greatly improved commerce in the area, and by the 1830s a village known as Halladay's Corners had built up. A sandstone quarry just outside the fledgling village was used to quarry the stones for the locks and dams at Chaffeys, Davis and Jones Falls. One of the most momentous events in Elgin's history was when Mormon missionaries arrived in the region in the 1830s and recruited many families. In 1834, one hundred and thirty five covered wagons left Halladay's Corners for Mormon settlements in the United States. It must have been quite a sight. For a brief time Elgin took on the Mormon name Nauvoo, meaning "beautiful". The present name of Elgin (pronounced Elg in, NOT El gin) is in honour of James Bruce, Lord Elgin, one time Governor-General of Canada.

Post-Canal

Settlement of the region dramatically increased after the building of the Canal. The Rideau Waterway, intended for military use, instead became vibrant commercial waterway, linking the communities in the region to outside markets. Prior to the locks on the St. Lawrence being built, it was the commercial lifeline for the port of Montreal, with thousands of tons of heavy materials (wood, minerals, grain, etc.), transported by boat from Canada's hinterland, via the Rideau Canal and the Ottawa River to Montreal. Also, in its first years, thousands of immigrants destined for Upper Canada travelled by boat via the Rideau Canal. The 19th century saw continued commercial use of the canal in transporting products from local sources: farming, lumbering, mining, milling of various types (grist, lumber, carding), cheese factories, distilleries, and other small businesses that were operating in the region.

Some of the distinctive architectural style of the region was created by the many skilled stonemasons who settled in the area on land granted to them after the completion of the Canal. It is in the Rideau region that you will see some of the finest examples of stone masonry in North America. The government even played a role in local architecture. After 1811, buildings were taxed based on the number of storeys and the type of material used in construction. To minimize taxes, settlers built one and half storey round log (squared on two sides) cabins, with one fireplace (if a fireplace was used for cooking it was not taxed).

For instance, in the 1851 census for North Gower, which at the time had a population of 1,777, it shows 3 stone houses, 21 frame houses, 162 log houses, and 91 shanty houses. By contrast, the richer community of Bytown boasted 121 stone houses, 6 brick houses, 556 frame houses, 430 log house and 12 shanty houses.

The years from the building of the Canal to the present day are briefly described in the History of the Rideau Canal section of this Internet site. The region today has undergone a revival of sorts. Buoyed by a thriving tourist and summer resident market, communities such as Westport and Merrickville are undergoing a makeover, catering to the transient visitor trade. However it still maintains its proud rural roots and old Ontario country charm.

The Ebbs and Tides

Although vibrant Rideau region communities such as Merrickville, Perth, Elgin, Westport, Smiths Fall, Newboro, Seeleys Bay and Kemptville are testimony to the vigour of the people who live in these areas, not all communities have survived the transition to the modern era. The ebb and tide of history have flowed through the region, changes have happened and will continue to happen.

Crosby, now a gas stop and a few residences, was, in 1850, a thriving community of 100 people. It was then known as Singleton's Corners. In 1888 the B & W Railroad (Brockville & Westport Railroad) passed through the community, and a train station, named Crosby was built. However, with the passing of the railroad, so too did Crosby fade.

Some communities have fallen almost completely into the dust. Bedford Mills, located at the west end of Newboro Lake (actually on Loon Lake), was, in 1831, the site of a mill, built by the Chaffey brothers at Buttermilk Falls. Benjamin Tett, the owner of the land, re-acquired it from the Chaffeys in 1834. In 1835, the government built a post office, naming it Bedford Mills (after the Duke of Bedford). Through the 1800s, lumbering provided employment and the town thrived. At the turn of the century, mica mining supported the community. In addition, a grist mill and a cheese factory had been established. But the mines played out, and by the 1920s, most of the town stood vacant. Much of the town has now fallen to dust, although the grist mill has been converted into a private residence.

A similar story to that of Bedford Mills can be told of the former community of Lake Opinicon. It sprang up in the mid-1800s at the western end of Opinicon Lake. Supported first by the timber industry, and then a phosphate mine, it became quite a busy port facility for the shipment of these and other products to market. But these products eventually played out, and the regions poor rocky soils couldn't support commercial farming, and so the community was eventually abandoned.

Not all communities that fell on hard times have fallen into the dust. Burritts Rapids, one of the earliest communities on the Rideau, stood to prosper as a thriving centre of commerce, and in fact it did so in the early years of the Canal. But the railways did not come to Burritts Rapids, the businesses left and homes were left vacant for many years. But now, with its beautiful location and proximity to Ottawa, it has become a community again, with many of the buildings restored to former glory by their current occupants.

Today and Tomorrow

Travelling the Rideau, it is easy to appreciate the history of the region. Travellers entering through the City of Kingston, with its marvelous stone architecture, are instantly transported to an earlier era. In much of the "old city" it is easy to visualize horse drawn carriages clattering down the street, with a host of pedestrians, the women in long dresses, the men dressed neatly in long jackets, all sporting hats.

The locks themselves are living history. The cranks (hand winches known as "crabs") that open the locks, turn today, opening the wooden gates, just as they when first opened in 1832. As your boat passes through the locks, it follows in the wake of a host of vessels from by-gone eras, canoes, skiffs, motor launches, sleek mahogany cruisers, steam yachts all the way to today's shiny smooth curved fiberglass boats.

In addition to towns and villages, the Rideau region for the last century has seen a settlement pattern of a different sort, becoming home to many who enjoy the pleasures of a fine Rideau summer. By the turn of the last century, many cottages and summer homes were springing up along the shores of the Rideau lakes. Today, as you cruise by cottages and residences along the shore, you will notice how the old and new blend together. Summer homes with wide verandas, quaint cottages, rustic cabins, modern houses with expanses of glass, all co-exist along the shores and islands of the Rideau Lakes. Remarkably, along the Rideau these differences in architecture don't clash, but blend together in a celebration of old and new. For many boating visitors, house watching is a fun pastime all on its own.

The first European settlers, arriving here over 200 years ago, would be amazed at the changes that have taken place along the Rideau. However, they would also recognize the roots that they put down so many years ago. The Rideau region has maintained its rural charm and tradition while at the same time providing all the modern amenities we are accustomed to today.

|

| Lower Bytown, 1845 - watercolour by Thomas Burrowes |

The greatest change in the region has taken place at the far end of the Rideau, in the City of Ottawa. Two hundred years ago, Ottawa was a wilderness with no human habitation. Now, it is a vital, bustling city, Canada's national capital. It has a charm and an ambience rivalled by few other North American cities. The Rideau Canal takes the visitor through the very heart of this beautiful city, with the final flight of 8 locks framed on one side by the architectural beauty of Canada's Parliament Buildings and on the other side by the majestic Chateau Laurier Hotel.

Ottawa is surrounded by a series of green belts, and new suburbs are springing up outside of these areas. The main development is to the south of the main city of Ottawa, and will not encroach too much on the Rideau itself. The Rideau Lakes region will continue to maintain it's rural charm for the foreseeable future to delight many more generations of residents and visitors.

A good regional archaeology site can be found at the Cataraqui Archaeological Research Foundation: Archaeology in Kingston and Eastern Ontario web page (CARF is now defunct, but the website remains as a resource). If you want to see who was living where in the late 1800s, have a look at: 1880 Township Maps for Rideau Area.

|