The Blue Edged Bowls

by Thomas McCrea

quoted from "A History of Leeds & Grenville" by Thad. Leavitt, 1879, p.76

When I first read this story in Thadius Leavitt’s 1879 book, it struck me as a fascinating example of the extreme privations experienced by the early settlers. These men and women spent all their time just trying to survive, to build a new life for themselves and their children in the Canadian wilderness. Although they were living in extremely rough conditions, it didn’t mean that they didn’t pine for a few luxuries, in this case, fine china bowls.

Thomas McCrea arrived in the Merrickville area (Montague Township) in about 1794. He was part of a family of United Empire Loyalists, all of whom came to Canada, first settling in Augusta Township. Later, the father, Samuel, and his sons, John, Edward and Thomas, settled in Montague Township. Thomas settled on Lot 3, Con. I of Montague Township. Although Leavitt doesn’t date this story, Glenn Lockwood speculates that it likely took place in 1797 or early 1798. - kww

The Blue Edged Bowls ...

The whole of the inhabitants, for miles around, had gathered to raise a log house ; at that time it took three or four days to complete the undertaking, men being very scarce. On the third day, after the last log had been placed in position, a council was held, and, after due deliberation and much discussion, it was decided that the settlement had so far advanced in civilization that some of the luxuries of life should be procured.

Our grist mill consisted of the primitive stump and pestle, the meal when ground being eaten from wooden bowls with wooden spoons. It was decided by the council that I should take one and a-half bushels of wheat, carry it from the site of Merrickville to Brockville, exchange it for one dozen bowls, one dozen iron spoons, the balance to be expended in groceries.

With the bag on my back I started for Brockville, before the sun was up, the road consisting of a winding path through the woods, with marks on the trees to show the direction. During my journey I was buoyed with the thought of the great surprise which was in store for our good wives, as the matter had been kept a profound secret from them. Never did a minister go out to preach the gospel feeling a greater responsibility than I felt resting upon myself.

I arrived at  Brockville on the evening of the second day, pretty tired, and the next day I exchanged my wheat for a dozen white bowls with a blue edge and one dozen iron spoons bright as silver, half a pound of cheap tea and the balance in fine combs and little things for the children. Early next morning, with a light heart, and carefully guarding my precious load, I started for home. Brockville on the evening of the second day, pretty tired, and the next day I exchanged my wheat for a dozen white bowls with a blue edge and one dozen iron spoons bright as silver, half a pound of cheap tea and the balance in fine combs and little things for the children. Early next morning, with a light heart, and carefully guarding my precious load, I started for home.

I arrived at North Augusta in the evening, and when crossing the stream at that place, on a log, the bark gave away and down I fell, some ten feet on the stones below, and horror of horrors, broke every one of my bowls. Never, never in all my life, did I experience such a feeling of utter desolation. How to go home and meet the expectant people, without the bowls, was an ordeal my soul shrank from, but there was no help for it.

I spent a sleepless night on my bed of hemlock boughs, and in the morning proceeded on my way with a sad heart. I found a few of the neighbors at my shanty waiting for me, and was greatly relieved when I saw that the loss was endured with Christian fortitude.

Pioneers and Millers

European settlement of the Rideau started in the 1780s with hardy pioneers venturing into the forest with the intent of homesteading. Some of these were United Empire Loyalists taking advantage of land grants, others just people looking for a better opportunity in life. The work of setting up a homestead was extremely difficult; on average, a single family could only clear a few acres of land per year. Outside of the desire for luxury goods such as china bowls, a more fundamental need was for mills.

The first demand was for planks to be used for roofing, siding, flooring and furniture – this required a sawmill. As agriculture grew there was the need for grist (flour) mills and later, carding (woollen) mills. The building of these mills called for a different type of person, an entrepreneur with mechanical knowledge and a willingness to take a risk on the Canadian frontier. He had to search out a good location for a mill, obtain the water rights from the government, haul in the needed iron work and then build the mill and associated dam. Since all mills at that time used a water wheel for power, it also meant that only a few locations, those with a drop (a head) of water, were suitable.

An interesting reference in this story is to the settler’s grist mill being a primitive stump and pestle. This was a slow and laborious process, pounding a club (a pestle) into grain placed in the hollowed-out top of a tree stump (forming a bowl to hold the grain). But flour was a fundamental staple and so, if a local mill wasn’t available, you either had to do it yourself or haul the grain to where it could be done for you. Also telling for the amount of work that a stump and pestle required to turn grain into flour, is that Thomas carried a heavy load of unground wheat (90 lbs / 40 kg), not the equivalent in ground flour (63 lbs / 28 kg), on his back, through the woods, all the way to Brockville (about 25 miles / 40 km), to use as barter.

The first mill on what is today the Rideau Canal was built by the government at Cataraqui Falls, just upstream of Kingston, in 1784. In fact they built two mills, a grist mill (built under the supervision of Robert Clark) and a sawmill (built by John Collins, likely supervised by Robert Clark). These were known as the King’s Mills.

The first mill built by an entrepreneur was that of Roger Stevens, who, in about 1790/91 erected a saw mill at the Great Falls, the location of today’s Merrickville. William Mirick took over that mill after Stevens drowned in 1793. Although some histories have Mirick adding a grist mill shortly after he took over Stevens’ saw mill, it appears that he didn’t add the grist mill until the early 1800s. A late 1790s petition from local settlers noted their great “inconvenience for the want of a good grain mill upon said River [Rideau], having been obliged for several years to go to the settlement [Brockville] upon the River St. Lawrence to get their grain ground.”

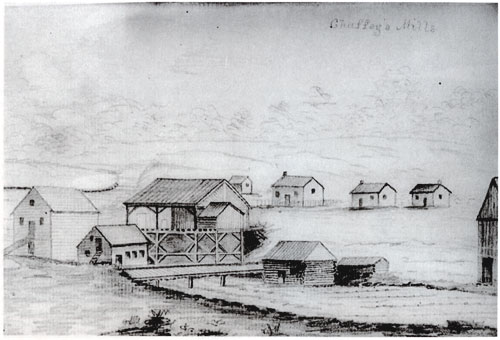

By the time of the building of the Rideau Canal in 1826, many of the rapids along the route sported mills. Some of these were simple saw mills, such as that of Walter Davis Jr. at Davis’ Rapids between Opinicon and Sand lakes. Some, such as the operations run by William Mirick at Merrickville and Samuel Chaffey at Chaffey’s Rapids, were extensive complexes incorporating a saw mill, a grist mill, a carding mill and often a distillery. These mills greatly assisted the settlers, allowing communities to grow and agriculture to flourish.

|

| Samuel Chaffey's Mills, 1827The milling complex set up by Samuel Chaffey, first established in about 1820. On the left is the grist mill, next to it is the carding mill. Across the rapids, the big building on the left is the sawmill and the log building beside the bridge is the distillery. Just visible on the right is Chaffey's barn and the buildings in the background are dwellings. "Chaffey's Mills, August 1827" by Thomas Burrowes, Baird Papers, Archives of Ontario |

|

| William Mirick's Mills, 1827This rough 1827 sketch shows the mills at Merrickville. The vantage point is from the position of the upper lock today. Although a little unclear in the descriptions, the buildings on the left are the carding mill and the saw mill. The bigger (two chimney) building is the grist mill. Sketch from the survey diary of John Burrows, May 1827, City of Ottawa Archives |

When the canal was built, the location of many of these mills (on rapids) was also the location needed to build the locks and dams. If he could, Colonel By by-passed the mills, doing so successfully at places such as Merrickville. In other places there was no other option but to buy out the mill owner. None complained since the payouts were fair and in some cases, such as with John Brewer, the mill owner was offered the contract to build the lock and dam at that location. Once the canal was completed, some mills, such as at Smiths Falls, were quickly re-established, using the canal dams for their head of water.

Today, you’ll find two fine examples of mills in the Rideau Corridor – both are open to the public. At the northern end is Watson’s Mill located in Manotick. Built in 1860, it has a fascinating history as recounted in the tale “The Ghost of Watson’s Mill.” It used a Rideau Canal water control dam (constructed in 1858) for its head of water and incorporated water turbines, the cutting edge of mill power technology for the day.

At the southern end is the Old Stone Mill in Delta, built in 1810, and today designated as a National Historic Site of Canada. The stone mill replaced an earlier wooden mill built by Abel Stevens (brother to the previously noted Roger Stevens). It was initially powered by a water wheel, but when turbine technology came along, a turbine shed was added as an extension to the mill.

Both mills have been partially restored to operating condition; Watson’s Mill uses some of its water turbines to power millstones and the Old Stone Mill has a working water wheel and millstones.

Sources:

Leavitt, Thad. W.H., History of Leeds and Grenville, Mika Silk Screening Ltd, 1972 (reprint of original 1879 book).

Lockwood, Glenn J, Montague, A Social History of an Irish Ontario Township: 1783 – 1980, Mastercraft Printing and Graphics, Kingston, 1980.

Murphy, William J., Tables for Weights and Measurement: Crops, University of Missouri Extension, 2008.

|