Washed Away

The Story of the Building of the Hogs Back Dam

by Ken W. Watson

"I was standing on top of it [the dam] with forty men, employed in trying to stop the leak, when I felt a motion like an earthquake, and instantly ordered the men to run, the Stones falling from under my feet as I moved off.” [Price p.108]. These are the words of Lieutenant-Colonel John By, describing the third failure of the Hogs Back Dam on April 3, 1829.

The story of the Hogs Back dam starts with the decision to put the entrance of the Rideau Canal in the location it is today (Ottawa Locks). Colonel By was attempting to avoid the hard bedrock excavation that would have been required if they had followed the route proposed by Samuel Clowes in 1823/24, which had the canal’s entrance at Rideau Falls. Colonel By’s final route (which surveyor John MacTaggart worked to figure out – see the story of Christmas 1826) avoided any significant bedrock excavation.

But it did mean that a big dam was needed at Hogs Back, which in the pre-canal era was known as Three Rock Rapids. Although the rapids themselves only had a drop of 1.8 metres / 6 feet (there were no falls here in the pre-canal era – see Jebb’s map in the Burritts family story), the dam had to raise much more water since it had to do two things. It had to flood the Rideau River all the way to Black Rapids in order to put a navigation depth of water over the lower sill of the lock at that location. It also had to put water over the upper sill of the locks at Hogs Back, the entrance to the canal cut to the Ottawa Locks. To do this, it had to raise the water of the river in this location by about 41 feet (12.5 m).

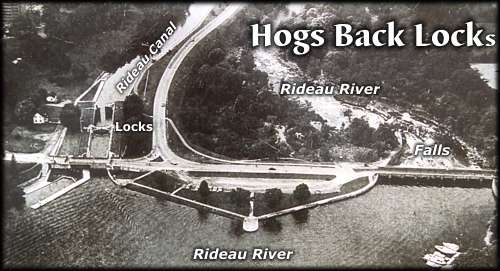

photo by: Parks Canada |

Hogs Back Lockstation (looking North)This is where the artificial channel of the Rideau Canal in Ottawa departs from the natural channel of the Rideau River. The artifical channel leading to the Ottawa locks can be seen on the left. The dam (now under a road and more modern landscaping) is in the middle and the waste water weir is on the right. The dam, located at the head of the original "Three Rock Rapids" raised the water in this location by about 41 feet. The river continues to flow as it always has, to the Rideau Falls and into the Ottawa River.

The top lock at Hogs Back is a "guard lock" - it isn't used for lifting, but rather was put in place as protection, particularly from spring flooding of the main lift lock. Although several were planned, this is the only guard lock built on the Rideau canal.

|

The dam was to be a stone arch dam, similar to the one we can see today at Jones Falls (the dam would be curved with the convex side facing upstream). The contract for the dam and the proposed three locks was awarded to civil engineer Walter Welsh Fenlon of Montezuma, New York (you can see the wording of the contract on the History of Hogs Back page). On May 4, 1827, Colonel By noted that “Mr. Walter Fenlon’s [bid] being much under all others, his tender has been accepted for all the said works [dam and three locks], and he is to complete them in two years from the day of signing the contract.” Philemon Wright and Sons of Hull were awarded the contract to build a cofferdam to allow the stone arch dam to be constructed. Wright partnered with Asha P. Osborne to do this work.

|

Profile of a stone dam. "a" on the left is the apron, "c" is the core clay puddle and "b" (on the right) is the stonework. Illustration from "Rideau Dams", by Lieutenant W. Denison, in "Papers on Subjects Connected with the Duties of the Corps of Royal Engineers", London, vol. 2, 1838

|

The type of dam they were to construct was different than dams built today. A stone dam consists of three main components: the “keywork,” the stones that form the near vertical back (downstream side) of the dam (usually about a 1:10 slope); the “core” of the dam, a watertight section in front of the keywork, generally made using “clay puddle”; and the “apron”, the sloping front of the dam which protects the watertight layer (clay) from erosion. It was an empirical design that worked as long as the watertight layer stayed watertight.

Clay puddle (or puddled clay) is clay mixed with coarse sand or fine gravel, wetted and then chopped, beaten and kneaded into a consolidated mass, about two-thirds of its original volume. If kept in an area where it would remain wet (i.e. below the water table) it would stay completely watertight. In some areas such as Jones Falls, there was an insufficient quantity of clay suitable for puddling, and “grouted broken stone” (small stones cemented under pressure) was substituted for clay puddle.

A problem with building a slackwater canal system (a system where dams transform the flow of a river into still water), is that the dams have to be built across the width of the river. What do you do with the river water while building the dam? At the time of the building of the Rideau Canal, there were essentially three choices. If the dam was small enough, you could build a by-wash (a water bypass) and then just build the dam in the river, letting the river water flow through the by-wash. This was difficult to do with larger dams and higher water flows. These necessitated either building sluiceways in the dam itself (this technique was used for the dam at Jones Falls) or using a cofferdam (a temporary dam upstream from the work area) to divert water around the construction of the dam in the initial phases, and then using the cofferdam to divert the water into the by-wash while you complete the dam. This cofferdam method was used at Hogs Back.

Another construction issue at the time was the height of the dam based on its intended use. By’s original thoughts were to follow European convention and construct overflow dams. That is, if you wanted to raise the water 10 feet (3 m), you built a 10 foot high dam and let the water flow over it. The original design for Hogs Back was for an overflow dam, over forty feet in height. After By’s first experience with the Rideau River in spring flood, he realized that the massive amount of floodwater, flowing over a dam, had the potential to erode the bedrock foundation at the base of the keywork, destroying the dam. So he quickly changed his plans, raising the height of many of his dams so that they were no longer overflow dams, and incorporating a waste water channel with a weir (water control mechanism).

In about June 1827, after his contract for the work had been signed, Fenlon started the stone dam construction on the east bank of the river and opened a quarry in this location. A cofferdam was built upstream to divert the water of the Rideau River to the west side. This essentially cut the width of the river in half, allowing Fenlon to construct half the dam in the now relatively dry east side. The cofferdam was made up in part of a jetty extending from the east bank, consisting of stones,

|

Profile view of a simple timber mill dam. The sloping side faces upstream. Illustration from "Rideau Dams", by Lieutenant W. Denison, in "Papers on Subjects Connected with the Duties of the Corps of Royal Engineers", London, vol. 2, 1838

|

earth and “rubbish”, and a timber dam, using the design of a mill log dam. This was made by building a sloping crib of large timber. The slope faced upstream, the pressure of the water actually helping to lock the timber in place. It was a simple, yet effective way to built a dam.

After completing the preparatory work, Fenlon started to build the stone dam. Work progressed so well that by the fall of 1827, Fenlon thought he was ready to close up his dam. To do this, he excavated a waste water channel (a by-wash) in the east bank, where the water of the Rideau River was to flow once his dam was raised. The bottom of his by-wash was about 27 feet (8 m) above the bed of the Rideau River. Once the river was raised to that height, it would flow through the by-wash.

The main portion of his dam had been raised to 37 feet (11 m) and work was progressing well on closing up the area between the completed portion of the dam and the west bank. But in February 1828, a sudden unexpected rise of water washed the west half away, essentially returning it to the state it had been in early fall 1827. Only the east portion of the dam remained.

Learning from experience, a slightly modified plan was executed. The concept of turning the water into the by-wash was sound if it could be effectively accomplished. The by-wash was excavated down another four feet and was made forty feet (12 m) wide. The largest timber that could be found, pine and hemlock, fifty to sixty feet long, were used in the timber dam portion of the cofferdam. Even with those lengths, the cofferdam could only be raised two feet above the bottom level of the newly excavated by-wash.

The Rideau River proved more than a match for these engineering efforts. On April 1, 1828, spring floodwater topped the cofferdam and eroded out the bank of the river. These floodwaters in turn severely damaged the stone dam.

Work began again on repairing the dam. However, Fenlon was a bit fed-up and begged to be released from his contract. He wrote a letter to Colonel By on June 18, 1828, in which he stated: “I find that I cannot possibly continue the Work at the prices that I am at present getting according to my Contract and I am the loser to a great amount on what I have already done. My humble prayer at this time, is, that Government would take the job and release me from all claims on the Contract. I trust I shall be allowed an estimate on what I have done in preparation for carrying on the work, and my losses I submit to the Consideration and discretion of the Commanding Officer.”

It appears that it was not until the fall of 1828 that Fenlon was released from his contract. It was noted by Colonel By and the on-site overseer, Capt. J.C. Victor of the Royal Engineers, that Mr. P. Wright and Sons had taken over part of Fenlon’s contract, a new contract being awarded to Wright on November 1, 1828, and in addition, that masons of the Royal Sappers and Miners were employed in building the keywork of the dam. Colonel By noted that “it will require great exertion during the whole of this winter to raise the arch Key work to a sufficient height to resist the spring floods;…”

The dam stood about 22 feet (6.7 m) high when Fenlon was released from his contract in November 1828. The Sappers and Miners and a crew of upwards of 300 labourers took over the job of completing the dam. Wright’s crews worked on the cofferdam.

With the experience of two dam failures behind them, they widened the by-wash channel to 60 feet (18 m), in order to provide lots of capacity (so they thought) to divert spring floodwaters. According to Colonel By, the dam had been raised 60 feet by late March 1829 (50 feet according to Lt. Denison, one of the other Royal Engineers). A height of 60 feet was 15 feet (4.5 m) above the required height of 45 feet (13.7 m), but Colonel By wanted the dam bigger and stronger. The base (keywork, core, apron) was over 200 feet (61 m) thick. The water had been raised the intended 41 feet (12.5 m), there was now flat water all the way to Black Rapids.

By March 28, 1829, the Rideau River was in full flood, with the water rapidly rising in front of the dam. According to Colonel By it was on that day that the dam started to leak and efforts began to try to stem the leakage (Lt. Denison says the leak started on April 2 and efforts to stem the leak started on that day).

On April 2, large scale slumping occurred in the lower part of the centre section of the dam. On April 3 the dam failed, the floodwaters washing much of it away. The quote from Colonel By at the beginning of this tale describes what happened when the entire dam failed.

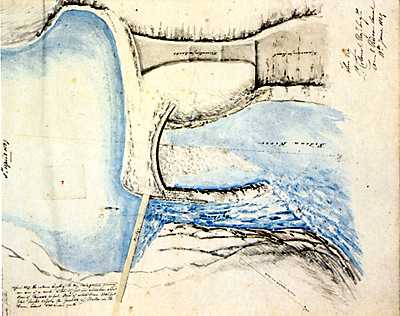

Hogs Back Dam - April 1, 1829 (looking west)

Hogs Back Dam - April 3, 1829 (looking west) |

In the upper image, the stone dam is complete, the water has been raised and is flowing through the bywash. The lower image shows that the dam has been completely breached. Plans No. 7 and No. 8 by John By, June 18, 1829, Library and Archives Canada, NMC 12892 24/80 and 25/80

|

The failure was due in part to inexperience with cold weather engineering. By the time the Royal Engineers fully took over the project in November 1828, all the earthen material placed on the apron above the existing waterline had frozen in place. It ended up being in essence one large lump of frozen earth sitting on top of unfrozen (below the waterline) earth. In fact it was noted that the ground froze so hard that winter that they had to use gunpowder to blast out earth to use for the apron.

The slumping that occurred on April 2 was the unfrozen portion settling down below the frozen earth, allowing water, now under extreme hydraulic pressure, to penetrate to the clay puddle and start washing it away. The dam had sprung a leak.

When this was noticed, attempts were immediately made to stem the leak by throwing everything they could find (brush, timber, clay, earth) into the source of the leak. The idea was that this material would temporarily stem the flow, allowing an effective repair to be made (it was a technique successfully used at Smiths Falls a couple of weeks later when a dam there had the same problem). They also had men clearing out debris from the by-wash channel, trying to increase this bypass flow of water.

But these efforts were far too late. The “earthquake” Colonel By described was the leak fully breaching the keywork of the dam. Now the entire flow of the Rideau River was going through the dam.

The reason there were no lives lost or even injuries, is that the frozen mass of earth held for some time, creating an arch above the rushing torrent. Lt. Denison reported that the arch of frozen earth stood for five minutes before the rushing water won out, and the arch collapsed into the void. Colonel By stated that “The force of the water was such that stones of two or three tons weight were tossed about as if they had been blocks of wood, and that the frozen earth was carried over the Rideau Falls, a distance of between five and six miles.”

By’s superiors obviously chastised him for the failure of the dam. Colonel By, in a letter replying to Sir James Kempt, wrote: “I feel much obliged by your Excellency’s calling my attention to the necessity of constructing the Dams perfectly impervious to water, and I beg to state on that principle I have acted from the commencement of the work.”

Colonel By was to make two changes to his construction plans for the dam. Wright’s cribbed cofferdam had suffered very little damage. So Colonel By planned to use this technique to construct a “temporary” dam made of cribbed timber filled with stone. The second change was the necessity of doing this when the water flow allowed and the temperatures were above freezing – so this new dam could only be worked on from the beginning of July to the end of November. In his April 23, 1829, report on the failure of the dam, he still appeared optimistic that a stone dam could be raised “at a future period.”

Lt. Denison says that any plans for a stone dam were abandoned as work progressed on the timber crib dam. Part of the original keywork dam still stood on the east side, but the entire west side of the river was open. To facilitate the transport of the large quantity of stone needed from the quarry, the Royal Engineers had a 1,160 foot (354 m) long “rail road” constructed in the spring of 1829 from the quarry to the dam.

The new timber dam construction was a model of simplicity. Timber cribs were laid on the bedrock of the river. As the first course of timber was laid, it was filled with large broken stones to resist the flow of the river. Once this base was secure, they laid courses of timber on top, creating an open timber framework through which the river flowed. The timber crib work was raised to the required height of the dam.

|

| Denison's profile view of the Timber Crib Dam showing the large broken stone piled on the back of it. Illustration from "Rideau Dams", by Lieutenant W. Denison, in "Papers on Subjects Connected with the Duties of the Corps of Royal Engineers", London, vol. 2, 1838. |

A roadway was built on top of the timber cribs and the cribs were filled with stone, starting from the flanks and working towards the centre. At the same time, earth, stone and rubbish was used to build out an apron in front of the cribs. This apron was huge, extending out almost 300 feet (91 m). Great quantities of large broken stone were piled onto the back (downstream) side of the timber cribs to help stabilize them.

photo by: Ken W. Watson |

| The broken stone placed on the back of the dam can still be seen today. |

While this work was going on, having now learned from three dam failures, they widened the by-wash channel to over 160 feet (49 m) in order to provide lots of capacity for spring floodwaters. Lt. Denison noted “The waste channel was widened nearly one hundred feet, by clearing away the earth down to the rock, a rough wall built to throw the water from the flank of the dam, rough stone steps laid behind the wooden framework of the waste-weir, to prevent the action of water upon the rock to which the sills were bolted ; in fact, every expedient which the skill of the officer in charge of the work could devise, or the means at his disposal enable him to execute, was put in practice to guarantee the work against accidents or failures.”

By November 30, 1829, the dam had been completed to the point where water was running through the by-wash. Although some minor slumping was noted, there was no failure of the huge mass of earth, timber and stone. It wasn’t as elegant as a stone arch dam, but it worked.

The failures of the Hogs Back dam weighed heavily on By’s mind. In a letter written on December 31, 1829, to his superior, General Mann, Colonel By stated “… I have the honour to report, that the dam at the Hog’s Back is nearly completed, and answers the desired object in every respect, having raised the Rideau River to the required height of forty-five feet, and thrown back six feet depth of water into the lock at Black Rapids, which proves my original levels at this place to be correct, and also the practicability of my project, which, when the dam gave way last April, was doubted by many, and to this annoyance I attribute the serious illness with which I was afflicted in April last.”

When the new dam and weir survived the spring floods of 1830 we can be sure that Colonel By and his men all let out a great sigh of relief.

|

| Hogs Back 1832 (looking north)This map shows the final configuiration of Hogs Back, from left; the two locks (one lift lock, one guard lock) leading into the channel to Hartwells and then Ottawa; the timber/earthen dam; the wooden waste water weir; and the waste water overflow channel. Illustration by Edward C. Frome in "Account of the Causes which led to the Construction of the Rideau Canal, connecting the Waters of Lake Ontario and the Ottawa; the Nature of the Communication prior to 1827; and a Description of the Works by means of which it is converted into a Steam-boat Navigation", by Lieutenant Edward C. Frome, in "Papers on Subjects Connected with the Duties of the Corps of Royal Engineers", London, vol. 1, 1837. |

|

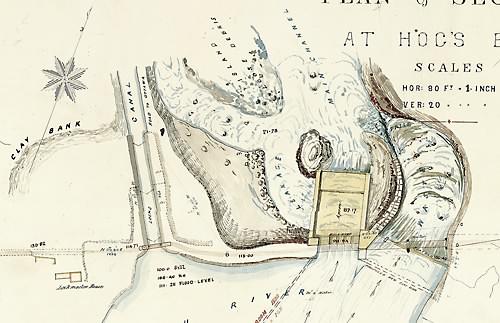

| Hogs Back - mid-1800s (looking north)This undated map, likely from the mid-1800s (or perhaps after the reconstruction of the weir in 1862), shows the configuration described in Frome's map (above). The site had continued problems with spring floods, the dam had to be repaired and the weir had to be reconstructed several times. Today a single, very large cement weir, controls the water flow. "Rideau Canal, Plan and sections at Hog's Back" by unk., n.d., Libary and Archives Canada, NMC 31191. |

Sources:

"Rideau Dams", by Lieutenant W. Denison, in "Papers on Subjects Connected with the Duties of the Corps of Royal Engineers", London, vol. 2, 1838, pp. 114-121.

"Account of the Causes which led to the Construction of the Rideau Canal, connecting the Waters of Lake Ontario and the Ottawa; the Nature of the Communication prior to 1827; and a Description of the Works by means of which it is converted into a Steam-boat Navigation", by Lieutenant Edward C. Frome, in "Papers on Subjects Connected with the Duties of the Corps of Royal Engineers", London, vol. 1, 1837, pp. 73-102.

"Construction History of the Rideau Canal," by Karen Price, Manuscript Report 193, Parks Canada, Ottawa, 1976.

|