Skeletons Under the Floor

The Story of Oliver’s Ferry

as adapted by Ken Watson from various sources

There is a legend told at Rideau Ferry of murder most foul, of travellers disappearing, of human bones found.

In the early 1800s, a Mr. Oliver set up a ferry business at today’s Rideau Ferry. His ferry, a rough hewn raft, linked roads leading from Brockville and Perth. Mr. Oliver had one unusual quirk. He would refuse to take travellers across to the far side after dark, preferring to put them up in his house overnight and send them on their way at first light in the morning.

His neighbours seldom saw the travellers in the morning. When asked about them, Mr. Oliver would simply say "They went on their way at first light. You must have been asleep". One strange thing kept happening though. Many of the travellers who had stayed overnight at Oliver’s house did not arrive at their destination... victims perhaps, the neighbours thought, of murderous highway robbers.

Years later, long after Mr. Oliver has passed away, a bridge was to be constructed to replace the ferry service. When the outbuildings on the Oliver property were dismantled to make way for the bridge, human bones were found under the floors and in the walls. The travellers had never left.

[the above version of the tale was adapted from Parks Canada's Rideau Canal Edukit]

|

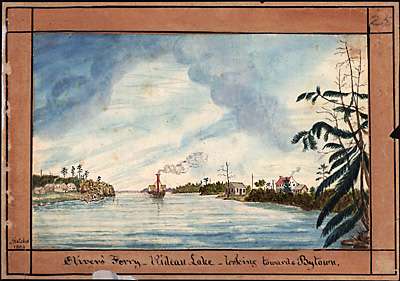

| Oliver's Ferry in 1830

Oliver's Ferry, August 20, 1830, by James Pattison Cockburn, Library and Archives Canada, 1989-259-1

|

The truth behind the legend is perhaps even more interesting than the legend itself.

In 1816, John Oliver, a Scottish pioneer, set up a ferry business on the south shore of “First Narrows” of Rideau Lake (on Lot 21, Con. V of South Elmsley Township), the location of today’s community of Rideau Ferry. This was a narrow (about 130 m / 425 ft wide) section of the lake, and the ferry linked a rough trail that led from Koyle’s Bridge (near the head of Irish Lake – connecting with the road to Brockville) to the newly formed community of Perth. The trail in the area of Oliver’s Ferry was described as “an avenue cut through extensive forest where the traveller had to pass over rocks, and wade through swamps and to surmount all the inequalities of the ground in its natural condition.”

When Reverend William Bell passed this way on route to Perth in 1817, he noted “At the ferry house, Mr. and Mrs. Oliver showed me every attention and sent their son [William] with me to the house of Andrew Donaldson, Esq. [a next door neighbour of the Olivers], where I remained the night.” John Oliver appears to have had a somewhat unstable personality, which culminated in his death by suicide (shooting himself) in about 1821. Reverend Bell noted that Oliver had forsaken all professions of religion and succumbed to his lunacy. His neighbour, Donaldson, didn’t fare much better. Originally a devout Presbyterian, he seems to have degraded over time. Bell noted that Donaldson had “a most outrageous temper” and a “malicious disposition.” Donaldson died in 1826.

Personality issues were passed on to John Oliver’s son William, who took up the reins of the ferry business. William was almost universally disliked. He had many disagreements with his neighbours, which often turned violent. He made “attempts” on the wife of William McLean from across the river.

On July 19, 1842, his violent nature caught up with him when cattle from a neighbour, the Toomys, trespassed onto Oliver’s property. Oliver confronted the two Toomy brothers in a rage and struck one of them. The Perth Courier in its July 26, 1842 edition reported that the Toomys retreated to their home and that Oliver followed them there. One of the Toomys grabbed a loaded gun and told Oliver to get back. As Oliver tried to wrestle the gun from Toomy, the gun discharged, shooting Oliver through the heart. He was killed instantly.

Reverend William Bell of Perth noted “The tragical death of William Oliver, at the Rideau Ferry on the 19th, creating at this time a universal thrill of horror. It was dreadful to think of a man so profanely wicked as he was, being sent into eternity in a moment.” Word spread fast, on July 20, Peter Sweeney, the lockmaster at Jones Falls, wrote in his diary “heard that Mr. Oliver was shot by a neighbour at Oliver’s Ferry.” The Toomys were jailed and later convicted of manslaughter.

William’s death wasn’t the end of the story. As related at the beginning of this tale, stories grew over time that some travellers, arriving late at night, stayed at Oliver’s house. But they were never seen making the ferry crossing the next morning. These stories developed into the legend that William killed these pour souls, took their possessions, dismembered their bodies and hid those remains. The legend says that when his buildings were torn down to make way for the new bridge across the narrows in 1874, human bones were apparently found in the walls and under the floors.

Reporter Rob Tripp of the Kingston Whig-Standard looked into the truth behind the legend in 2007. The papers of the era never actually reported bones being discovered when the buildings were torn down to make way for the bridge. However, the Perth Courier, in 1873, the year when bids were being assembled for the construction of the bridge, did run a story reporting the “discovery of a human skeleton under the platform of a house near the wharf that was undergoing repairs.” Dr. Deslonges of Perth was asked to examine the bones which he reported to have lain in the ground for as much as 25 to 30 years. Hence the kernel of a legend: a human skeleton, the right time period, a “profanely wicked” man – the legend of lost travellers at Oliver’s Ferry grew over time.

In the Kingston Whig-Standard article, Tripp points out a problem with the legend. The discovery of a human skeleton actually took place in Petawawa, hundreds of miles away. Dr. Deslonges of Perth just happened to be visiting at the time and was asked to examine the bones, hence the report in the Perth Courier.

No human bones have (as yet) been found in or under the buildings at Oliver’s Ferry.

Sources:

Kennedy, James R., South Elmsley in the Making 1783-1983, Township of South Elmsley, 1984.

Parks Canada, Heritage Trails, Exploring the Rideau Canal – Edukit, Parks Canada, n.d. (c.1999).

Tripp, Rob, “Profanely Wicked” in Unlocking the Rideau, The Kingston Whig-Standard Special insert, June 30, 2007, pp 17-18.

Skelton, Isabel, A Man Austere, William Bell, Parson and Pioneer, The Ryerson Press, Toronto, 1947.

Watson, Ken W. (ed), The Sweeney Diary: The 1839 to 1850 Journal of Rideau Lockmaster Perter Sweeney, Friends of the Rideau, Smiths Falls, Ontario, 2008.

|

| Oliver's Ferry in 1834

Oliver's Ferry [looking North], Rideau Lake by Thomas Burrowes, Archives of Ontario, C 1-0-0-0-25

|

|