PART I OF VI: THE CANAL

|

| The Chateau Laurier reflected in the Rideau Canal from the Ottawa locks. It's the most-visited station along the 202-km route. |

|

| "Captain Jack" Hearn, a self-professed old coot, has been the harbormaster at Westport for the past 20 years. Many a boater has shared a beer and a tall tale with one of the waterway's most colorful characters. |

|

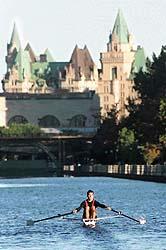

| Sculler John Muir gracefully parts the Rideau Canal along Colonel By Drive heading for downtown and the Laurier Ave. bridge. |

|

| A canalman stands between parting locks at Hog's Back, named for a spine of rocks protruding from the rapids. |