PART VI OF VI: ...TO KINGSTON

|

| Don Warren, "the Defender of the Rideau" has worked tirelessly for 30 years to preserve the canal's rural and historical character. |

|

| The spectacular view from Jones Falls is a prime attraction in this four-lock landmark. It is the second-busiest station in the canal system - after Ottawa. |

|

| A series of boats are jammed into the head lock at Jones Falls for the last run of the day. The entire four-lock descent can take a long as two hours. |

|

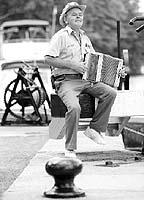

| Canalman Raymond Laforest strikes up a tune at Jones Falls locks. He and his magic accordion are legend among boaters the length of the canal. |