PART II OF VI: 'Ottawa was the canal'

|

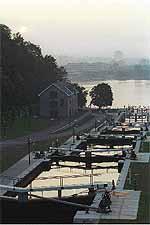

| Sun sets over the Ottawa locks where the Ottawa River flows into the canal. Those with keen eyes will spot Quebec in the backdrop. |

|

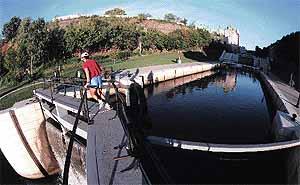

| Canoe enthusiasts James Smith and Andre Nimigan paddle near the Bank St. Bridge. The canal hosts all varieties of boats. |