The Irish Creek Route

The Canal That Wasn't

by

Ken W. Watson

In 1816, a young Royal Engineer by the name of Joshua Jebb did a survey of the Rideau Route. While he mapped the present route of the Rideau Canal his preferred option was to take a shortcut via Irish Creek and Lower Beverley Lake. This is a description of that route and why, by 1826, it was never considered a viable route for the Rideau Canal. This article assumes that you have some familiarity with the present day route of the Rideau Canal

| Note: This page is a web presentation of a PowerPoint talk that I gave to The Delta Mill Society. I've tried to maintain the flow, using text in place of my verbal narrative. My talks are highly visual, I've reproduced most of the slides in smaller format on this page. No Q&A at the end, but feel free to email me any questions. |

Today, the iconic Old Stone Mill in Delta, Ontario, built in 1810-11, sits between two lakes, Upper and Lower Beverley. These lakes were part of the proposed Irish Creek Route.

If the Irish Creek Route had been chosen for the Rideau Canal, this is what we would see there today.

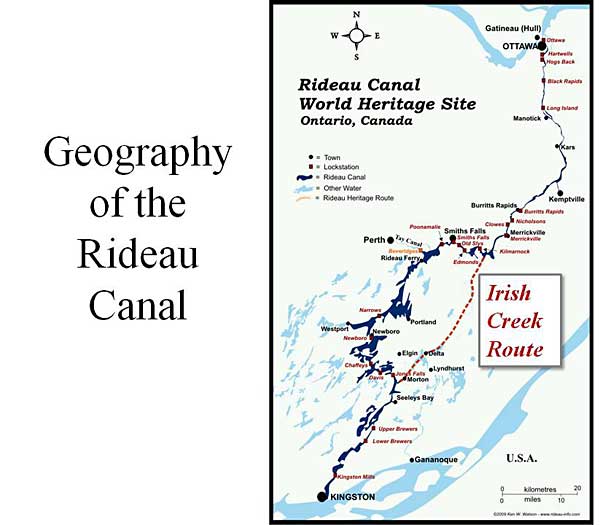

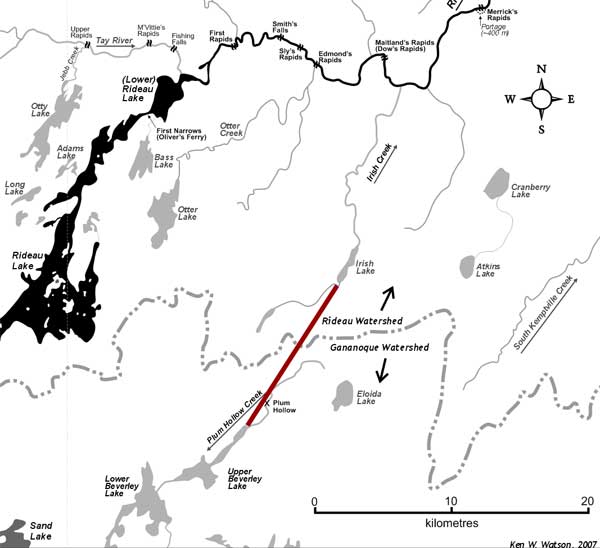

The red dashed line on this present day map of the Rideau Canal shows the plan for the Irish Creek Route. This route was to be a shortcut in the middle of the Rideau Route, bypassing the Rideau lakes. The northern and southern part of canal were to be as they are today (Ottawa to Merrickville and Whitefish Lake to Kingston), the Irish Creek Route would start where Irish Creek joins the Rideau River, near Jasper, just a bit south of Merrickville. It would then continue south to Irish Lake, then overland to Upper Beverley Lake, through Delta, into Lower Beverley Lake, up the White Fish River (today's Morton Creek) and then back into the Rideau Canal as we know it today at Morton Bay.

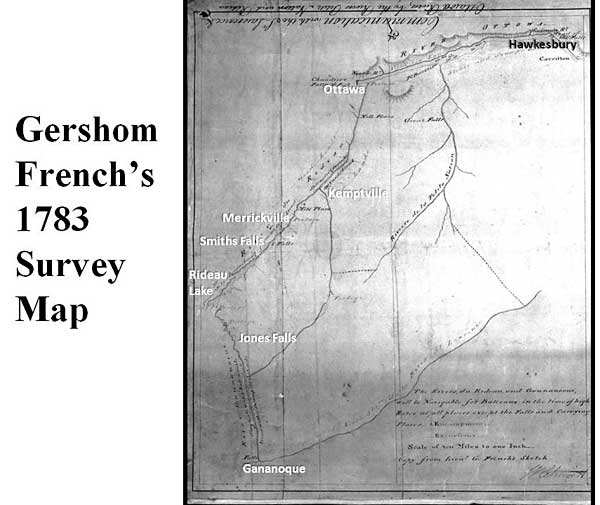

We'll step back now to the first map of a portion of the Rideau Route. This map is from Lt. Gershom French's survey in 1783. He left from Montreal, heading up the Ottawa River to Rideau Falls. He had a native guide to show the way. French wasn't looking for a navigation route, he was looking for land to settle. So, at various points along the route he and his survey party would do traverses inland to assess the character of the land.

The map is very simple, but we can see various present day aspects, including Rideau Lake. The watershed divide is the same as today, at Newboro, once over that he was into the southern Rideau Lakes. A big difference back then, is that water from these lakes flowed into the White Fish River, the head of which was at Jones Falls. It flowed though today's Morton Bay into Lower Beverley Lake and then south to the St. Lawrence River at Gananoque. This is the native paddling route that French followed. At the time there was no water connection between the Rideau Lakes and the Cataraqui River which flowed to Kingston.

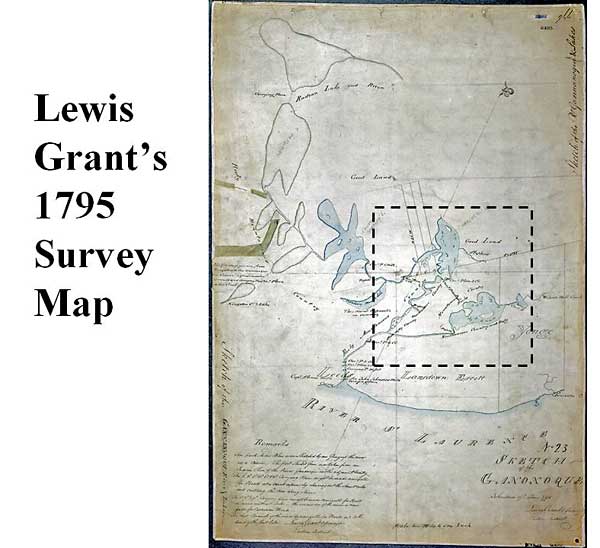

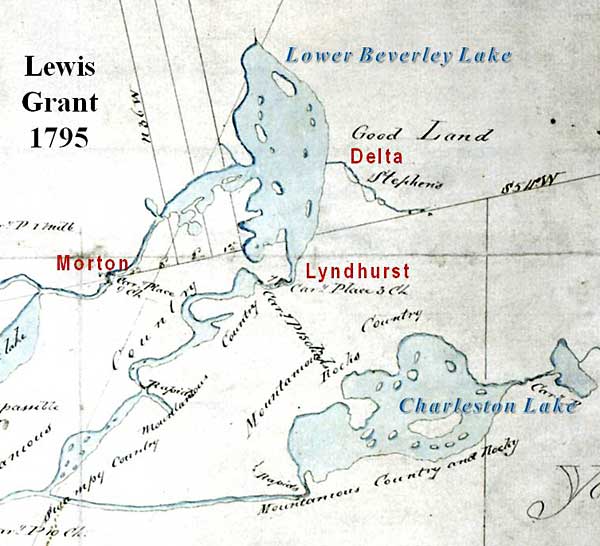

The next good look at part of the route comes of surveyor Lewis Grant's 1795 survey map. He started his survey due to pressure to get the area around the Delta surveyed since Abel Stevens was after the water rights to the rapids between Upper and Lower Beverley lakes and wished to create a settlement in that spot. Stevens applied for those right on November 4, 1794 and was granted them in June of 1796.

Grant started off by going up the Gananoque River and then mistakenly into Charleston Lake. He realized his error and then continued up into Lower Beverley Lake and eventually up the White Fish River and into Sand Lake. The blue on the map represent what he actually mapped.

Looking at the area around Delta in detail, you can see that Grant has "Stephen's" labeled in the pre-Upper Beverley Lake area (then two smaller lakes)

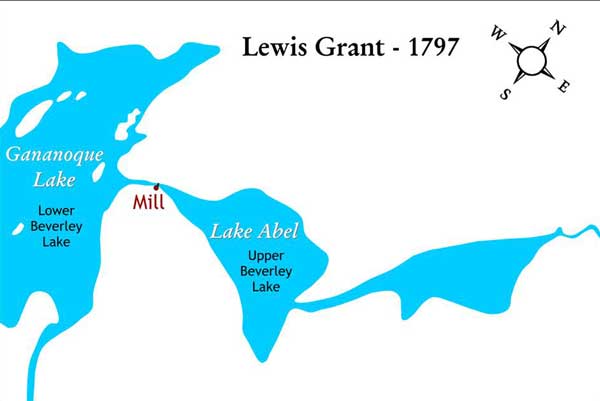

This is a trace of the outline of the lakes from Lewis Grant's 1797 lot and concession survey map. Abel Stevens already has his mill set up (eventually two wooden mills, a grist mill and a sawmill) and may have placed a dam between the two sections of Upper Beverley Lake (to impound more water)

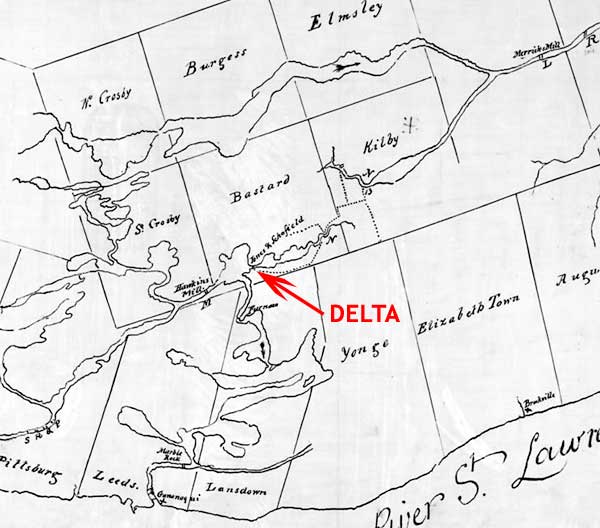

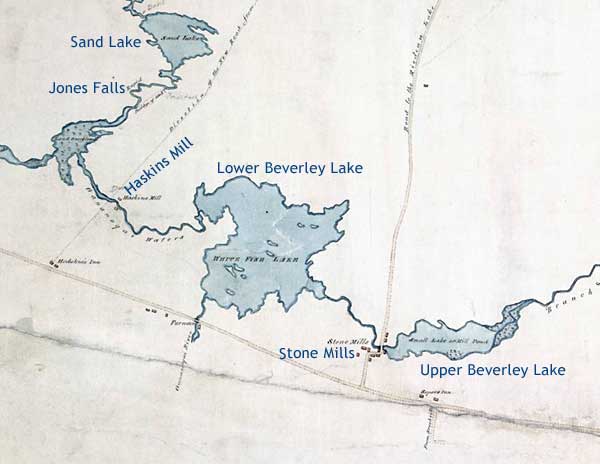

We now jump to 1815, a year before Joshua Jebb was to do his survey of the Rideau Route. This map shows "Jones and Schofield" at the location of Delta. It was William Jones and Ira Schofield who built the Old Stone Mill in 1810-11. The small community that grew up around the mill became known as Stone Mills.

To the left of Jones and Schofield we see Haskins Mill in the location of today's Morton. Lemuel Haskins built a dam and mill in this location in about 1805. It was Haskins' dam that raised the level of the White Fish River to a point where it started to flow south to the Cataraqui River. This was a huge change to the watershed and very significant in that it made this section navigable by boat for the first time. Jebb would take advantage of this in his survey, paddling his canoe through drowned forests on this way to the Cataraqui River.

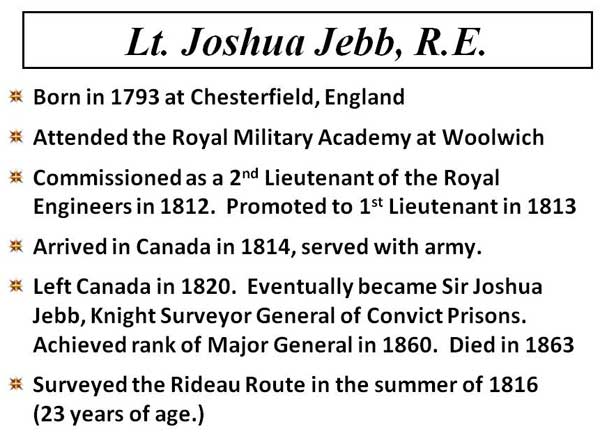

We now introduce the main player in this story, Lieutenant Joshua Jebb, Royal Engineer. During the War of 1812 between Canada and the U.S., the British military realized how vulnerable the critical naval harbour at Kingston was to being re-supplied. The St. Lawrence River, which bordered the U.S., was too dangerous, they needed a safe supply route from Montreal to Kingston. That safe route was the Ottawa River and the Rideau Route.

In 1816, a young Royal Engineer, Joshua Jebb was tasked with doing a detailed survey of the Rideau Route from the Ottawa River to Kingston. He was looking for a navigable waterway for a batteau, a type of small barge in common use at the time, draughting less than 3 feet.

He set out with a survey party in July 1816 to fully map the route.

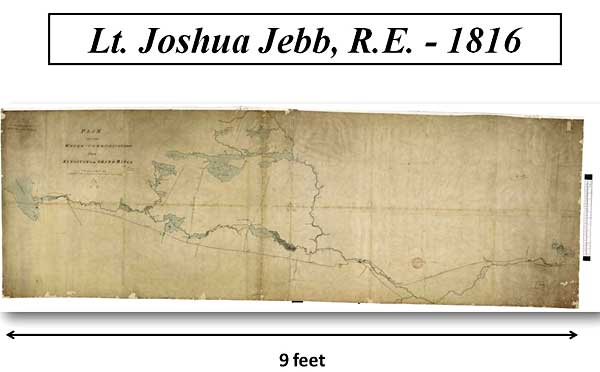

This is the map he produced, a stunning work given the time period and short duration of his survey.

This is the centre portion of his map which illustrates his two choices of route. One is the upper route, via the Rideau Lakes (Smiths Falls to Jones Falls) and the second, the topic of this talk, is the lower route, the Irish Creek Route which extends from Jasper to Morton. Jebb saw this as a short cut that could save several miles of navigation. We can see an immediate shortcoming with that route, no water in the middle (Plum Hollow area) - but that didn't deter Jebb, he had an innovative plan for that part of the route.

Let's have a look at the route in detail.

This shows Irish Creek from its headwater in Irish Lake to its outflow into the Rideau River. It was a small meandering creek with part of it flooded due to a mill dam. Jebb saw this as easy to make navigable through dams and locks.

You can paddle parts of Irish Creek today. If you do, you'll encounter a problem Jebb likely faced, beaver dams. A change from Jebb's day is that much of the forest has been cut down and the lower part of the creek has been flooded by the raised water levels of the Rideau River (from the dam at Merrickville).

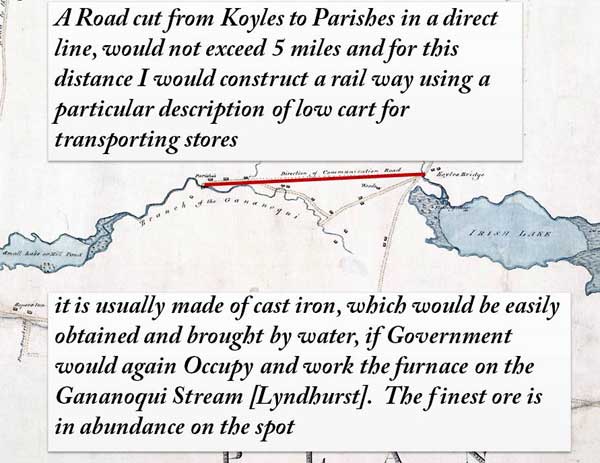

This shows the overland portion of Jebb's Irish Creek route, a 5 mile (8 km) section from Irish Lake to Upper Beverley Lake which Jebb has labeled as a "Small Lake or Mill Pond."

This schematic map (at a different orientation that Jebb's map above) shows the 5 mile overland section. It climbs over the watershed divide between the Rideau River watershed and the Gananoque River watershed.

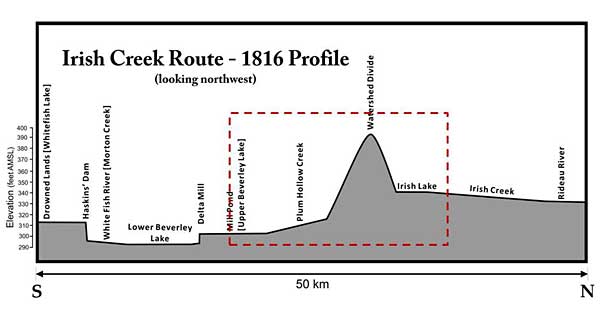

This is a cross-section with the vertical scale exaggerated, the dashed red outline is the overland area of the route where it climbs over the watershed divide.

This images includes quotes from Jebb's report explaining how he planned to span the no-water gap. He was going to build a rail road from Irish Lake to Upper Beverley Lake. Cargo from boats would be offloaded and put into iron carts that would run along the rail way. He notes that the carts could be locally built if the iron foundry at Lyndhurst (which burned down in 1810) was rebuilt.

This is the last section of the Irish Creek Route, from Upper Beverley Lake to Morton Bay (near when Haskins' Mill is located). White Fish Lake (centre) is today's Lower Beverley Lake and Stone Mills is today's Delta. To the far left is a small lake labeled "Land Overflowed" - this is the location of today's Whitefish Lake (part of the main Rideau Canal). Once into this location, Jebb's plan would follow the present day course of the Rideau Canal to Kingston.

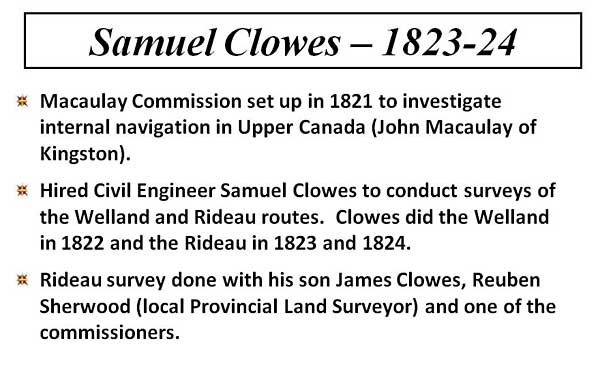

The next surveyor of the Rideau Route and the one that killed the idea of the Irish Creek Route, was civil surveyor Samuel Clowes. He was hired to do a full survey of the Rideau Route and in particular investigate the viability of the Irish Creek Route. His survey spanned 2 years, 1823 and 1824, and it was the first survey to run levels (elevations) of the route.

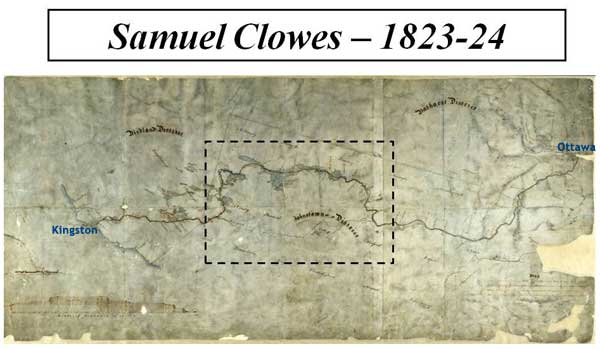

This is the map the Clowes produced. While not quite as pretty as Jebb's map, it is in fact more accurate. Telling in this particular copy of Clowes' map is that the Irish Creek Route is only pencilled in, not inked and coloured.

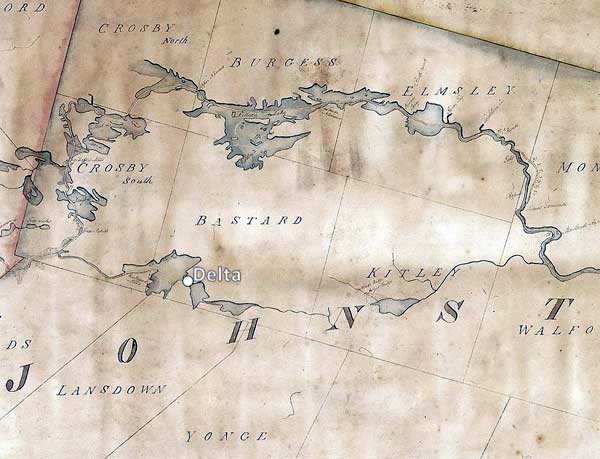

This is the centre section of a cleaner copy of Clowes' map. As with the centre of Jebb's map, the difference between taking the route through the Rideau Lakes versus taking by way of Irish Creek is clearly visible. The Irish Creek Route is shorter, but it has no water in the middle. The top of the Rideau Lakes route is Rideau Lake, a very large body of water. By this time, the route was being investigated for larger size boats, Clowes was tasked with coming up with the plans for a route that would have 4 feet, 5 feet or 7 feet of water depth (he costed out the canal for those 3 depths) along the entire route, a continuous waterway.

Clowes discounted the Irish Creek Route for a number of reasons, as shown below.

The first thing that Clowes discounted was an assumption that the Irish Creek Route had a lower summit elevation than a route through the Rideau Lakes. It turns out that Clowes was both right and wrong, we'll look at that in a little bit.

To make a continuous waterway Clowes needed water. To get water to the top of the Irish Creek Route, Clowes noted that a feeder canal would be needed from Rideau Lake. Since the Rideau Lakes route already had water, it was the less expensive (and much more logical) option.

Previously I mentioned that Clowes was right and wrong. He was wrong that summit elevation of Rideau Lake was lower than that of the Irish Creek route - the latter is in fact about 6 feet lower than the 1820s level of Rideau Lake. However, he is correct in that two summits were present and we'll shortly have a look at the total elevation difference (which equates to the number of locks required).

Finally, Clowes addressed the issue that the Irish Creek Route was shorter than the Rideau Lakes Route. He agreed with Jebb that the route was longer, but the advantages of going by way of the Rideau Lakes more than outweighed the added length.

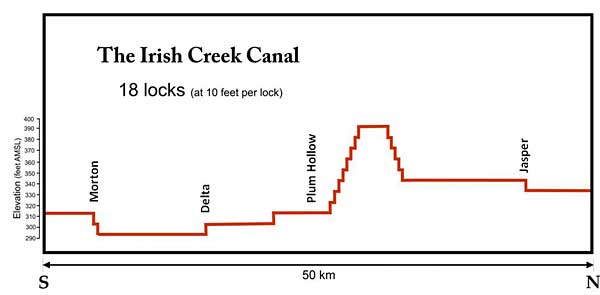

If the Irish Creek Route had been chosen, it would have required about 18 locks to overcome 185 feet in elevation change.

Was Clowes correct. Yes he was for the reasons shown above. The Rideau Lakes route actually has less elevation change than the Irish Creek Route and its summit is a body of water - perfect for a canal.

By the time Lt. Colonel John By, the architect of the Rideau Canal, arrived on the scene in 1826, the route by way of the Rideau Lakes was firmly established. He never considered the Irish Creek Route.

|