The Rideau Canals that Never Were

by

Ken W. Watson

Note: This article first appeared in the Winter/Spring 2011 edition of Rideau Reflections, the newsletter of the Friends of the Rideau (www.rideaufriends.com).

|

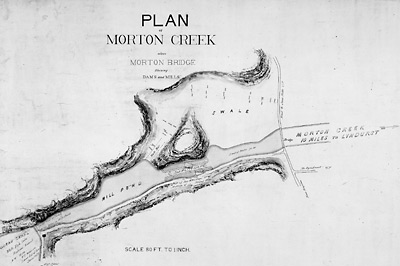

Morton Locks

An engineering drawing for the late 1800s proposal for a Rideau-Gananoque Canal. This diagram shows two locks at Morton (in the location of George Morton’s mills) that would connect the Rideau Canal with the Gananoque River system. From: Plan of Morton Creek above Morton Bridge shewing dams and mills, nd, Library and Archives Canada, 016373.

|

We’re all familiar with the route of the Rideau Canal. The surveys that led to the decision to use the route that the canal follows today has been well documented in the book, The Rideau Route. But what about other canal proposals? These fall into three general categories: seriously studied, passing thoughts and fictional creations. The first two categories will be briefly reviewed in this article and then a couple of examples of the latter category will be examined in more detail.

In the category of serious proposals for alternate or additional canals, the best known is the Irish Creek Route, proposed by Lt. Joshua Jebb in 1816, to take the route of the Rideau up Irish Creek (Jasper), into Lower Beverley Lake, then up Morton Creek to present day Morton Bay (and from there following the present route to Kingston). Lesser known are two late-1800s proposals for connector canals, one leading from the Rideau to Gananoque (it would have connected to the Rideau Canal with two locks at Morton), and a second proposal to connect Devil Lake to the Rideau Canal with several locks at Bedford Mills. There are engineering drawings for both of these proposals.

During the building of the Rideau Canal, in the category of passing thoughts (mostly by John Mactaggart), there was the Dow’s Swamp Canal (to link the Rideau Canal at Dow’s Lake with the upper Ottawa River (above Chaudière Falls) and there was the Richmond Canal (up the Jock River to Richmond). Mactaggart also, in 1827, proposed a canal to Perth, a bit different than the route followed by the 1st Tay Canal in 1834.

In the category of fictional creations is a route that would have led overland from Murphys Bay in Big Rideau Lake to Newboro Lake, and a lock that would connect Hart Lake with Opinicon Lake. We’ll start with this latter tale, since the root of the story is known and is the reason for the name “Deadlock Bay” in Opinicon Lake.

The Dead Lock

|

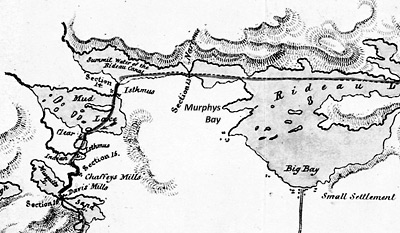

Drummond Mill

This 1833 map shows the location of the Drummond Mill at the outlet of Hart Lake. Shown as 6 on the map (upper centre), the map legend states: “Outlet of Hart Lake into Opinicon Lake. Crown Reserve. Mr. Drummond has built a Mill on this Site.” From: “Diagram of the Townships through which the Rideau Canal passes from the Narrows to Brewers Upper Mill; showing the Lakes which fall into the same” by G. Nicolls, November 11, 1833, National Archives of Canada, NMC 41071.

|

|

The “Dead Lock” on Opinicon Lake

Parks Canada archaeologist Jonathan Moore poses beside the large cut stones that once formed a dam at the outlet of Hart Lake. There were misinterpreted to be abandoned lock stones, leading to the name “Dead Lock.” (Photo by Ken W. Watson)

|

Deadlock Bay is located on the south shore of Opinicon Lake. This is the spot where the outflow from Hart Lake enters Opinicon Lake. The name “Deadlock” came from a tale that this was to be a location for a Rideau lock, connecting Hart Lake to Opinicon Lake, and that work commenced on it but was then abandoned in favour of the route the canal follows today (hence a “dead lock”).

If you go to the head of the bay (either paddling or in very shallow draft boat) you’ll find a short portage that leads to Hart Lake. Walk up that portage and then over to the rapids. Partway down those rapids you’ll see large cut stones on both sides of the channel. It is these stones that led, in the late 1800s, to the fictional tale of a “dead lock” – to those viewing the stones with no historical context, they looked like canal stones – hence the root of a tale of an abandoned lock. The stone are in fact mill dam stones and mill foundation stones, originally put here in 1832/1833 (with some perhaps re-located in 1872 when a canal reservoir dam was built in this location).

A reason that there was no local memory of this mill is that Opinicon Lake was very sparsely populated until after 1872 when John Chaffey built his mill and established the community of Chaffeys Locks (until that time it was just home to the lock staff). All we know today about the mill at the outlet of Hart Lake is that it was built by a Mr. Drummond and that it was in existence in 1833 (see the adjacent map). It may have been built by Robert Drummond after he completed his contract work on the locks (including the nearby Davis Lock). Drummond died in 1834, and perhaps the mill was abandoned at that time. What was left was a number of large cut stones, similar in size (although not in composition or quality) to those used in the locks.

There may also have been an aboriginal memory that this was part of the canoe route from Kingston to Opinicon Lake prior to the early 1800s, when mill dams made the section between the southern Rideau lakes and the Cataraqui River navigable. Prior to that time, if you wanted to go from Kingston to Ottawa by canoe, you travelled up the Cataraqui River to its headwaters in Loughborough Lake, then through Hart Lake to Opinicon Lake. Perhaps it was both the story that this was a navigation route and the sight of large cut stones that led someone to conclude that this was the start of a Rideau lock.

Another possibility is that this tale started in 1872 when a canal dam was erected in this spot (to make Hart Lake a reservoir lake for the Rideau Canal). Some of the original (long abandoned) cut stones were likely used for this second dam, and perhaps the workers building this second dam speculated that these might have been stones originally cut for a lock. That reservoir dam was torn down by local farmers sometime prior to 1910 (to reduce the amount of flooding of Hart Lake).

Today, most people don’t know about these stones (they are off the beaten path) – but it is an interesting place to visit and get an appreciation for how the story of a “dead lock” could have started.

Murphys Bay Route

|

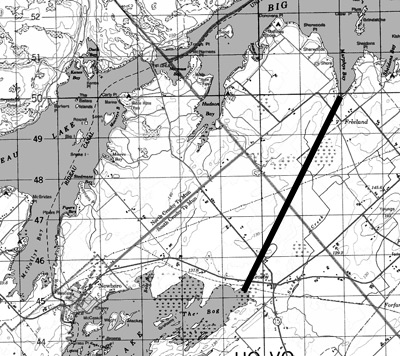

Murphys Bay Canal

The thick line (6 km long) connecting Murphys Bay of Big Rideau Lake with Newboro Lake at Crosby is a general representation of the tale of an alternate Rideau Canal route. Section from NTS Map 31C/9, 1994.

|

|

The Route of the Rideau Canal, 1830

This 1830 map shows the originally proposed and final route (one and the same) of the Rideau Canal through Narrows and then across the Isthmus to Newboro Lake (then known as Mud Lake). The words “Murphys Bay” have been added to the map for clarity. From: "Plan of the Line of the Rideau Canal Showing the Section of Each Work" by Lt. Colonel John By, July 8, 1830. Library and Archives Canada, NMC 43041.

|

The second fictional Rideau Canal route is one that would have led from Murphys Bay in Big Rideau Lake to Newboro Lake. There is a story that says that a warehouse and wharf were constructed here at that time in anticipation of the canal coming through. Some versions of the story say that the fledgling village of Portland was prepared to re-locate to Murphys Bay in anticipation of the business created by the canal.

Now, while the story that a warehouse and wharf were constructed may well be true, it likely wasn’t for the Rideau Canal passing through this spot. There were never any official plans to take the canal by way of Murphys Bay, which would have required a 6 km canal cut to link it with Newboro Lake (as opposed to the 1.5 km cut through the Isthmus). The only kernel of truth that I can think of, is that when difficulties were encountered in the Isthmus excavation (hard and leaky bedrock), alternative routes were investigated, perhaps including a route from Murphys Bay to Newboro Lake – but I’ve never seen any documentation of this. In the end, Colonel By solved the excavation problem by adding a lock at Narrows (to raise the level of Upper Rideau Lake and reduce the amount of excavation required through the Isthmus at Newboro).

Murphys Bay does have an interesting history in its own right. While it is named for David Murphy, who had a farm here, there was an earlier settler in this spot, an “old man Lindsay.” Lindsay had a role in the settlement of Perth in 1816. He owned a scow and this was used to transport settlers to the Tay River in May 1816 (prior to John Oliver setting up his ferry service in the fall of 1816 at today’s Rideau Ferry). They boarded the scow at the location of today’s Portland. One can imagine the trepidation of these settlers as they headed out onto the waters of Big Rideau Lake to make a life for themselves in the newly established community of Perth.

The stories of the Rideau, whether true or not, are part of the rich heritage fabric that makes the Rideau such an interesting place.

- Ken Watson

|