Indigenous Use of the Rideau Waterway

by

Ken W. Watson

Note: This article first appeared in the Spring/Summer 2018 edition of Rideau Reflections, the newsletter of the Friends of the Rideau (www.rideaufriends.com).

| |

|

| |

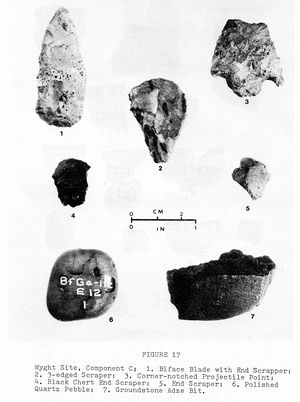

Artefacts from the Wyght Archaeological Site

From “The Wyght Site: A Multicomponent Woodland Site on

the Lower Rideau Lake, Leeds County, Ontario” by Gordon D.

Watson, Master’s Thesis, Department of Anthropology, Trent

University, 1980.

|

People arrived in the Rideau area at some time after the retreat of the glaciers that used to cover this area. By 13,000 years ago the glaciers were gone, replaced in the northern Rideau (Ottawa to Big Rideau Lake) by the Champlain Sea. The landscape had been depressed by the ice to below sea level, allowing Atlantic ocean waters to flow in. However, the land was rebounding (rising) and by 11,000 years ago the Rideau region had risen above sea level, the sea was gone. We have no direct evidence of people dating to the Champlain Sea era, but they most likely were here, as people would have followed wildlife now occupying the new ice free regions. A fluted point, characteristic of paleo-native people, dating to between 10,000 to 11,000 years ago, was found near Lower Rideau Lake. These people were nomadic hunter-gatherers, often following large game animals such as caribou. Conditions were still sub-arctic in this area and the number of people very low.

We have much more evidence from the archaic period (10,000 to 2,800 years ago). The climate was warming, the type of wildlife and vegetation that we see today becoming more common, and at this point people were travelling along the waterways in dug-out canoes. Trade with people in other regions is evident with the discovery of artefacts, such as copper beads, not local to this region. Perhaps the most famous archaeological site in this area is the Wyght archaeological site on Lower Rideau Lake which saw use, as a seasonal occupation site, from about 6,000 BC to 1,100 AD. It was in an ideal location, the junction of several waterways, the Rideau lakes, Tay River and Rideau River.

The archaic people hunted a variety of animals, everything from squirrels to moose. They also ate fish and shellfish; plants such as lily roots, cattail roots, and wild rice; and a variety of nuts and wild berries. They had a number of different tools to help them in their hunting and food preparation including projectile points, adzes, gouges, knives and hide scrapers. In about 1,000 BC, pottery started to be used, shard remainders can be found all along the Rideau. White tailed deer, by then the most common large game animal in this region, became the favourite of native hunters.

The Rideau corridor, in addition to being a seasonal hunting, fishing and gathering area, was also used as a travel way between the Ottawa Valley and the St. Lawrence River/Lake Ontario. The main route led from Ottawa to Gananoque, since the part of the Rideau today occupied by Whitefish and Cranberry lakes was not navigable by canoe at that time. That canoe route went from the Rideau River to the Rideau lakes to the White Fish River (Jones Falls to Lower Beverley Lake) and down the Gananoque River. The Cataraqui River was used as a secondary southern route to the Rideau, going from Lake Ontario, up the river to its headwaters in Loughborough Lake and from there to Hart Lake and then to Opinicon Lake.

We know the general location of the original long portages along the Rideau such those at Newboro, Chaffeys and Jones Falls (each over a kilometre in length). Used for thousands of years, two hundred years of disuse and cultural disturbance have obscured most of these. The route at Newboro is obscured by cultural disturbance, although archaeological evidence of a campsite at the Newboro lockstation, dating to the Point Peninsula cultural period (early AD), has been found. The route past Chaffeys was abandoned after dams were established for mills at Davis and Chaffeys, c.1820, and a new, shorter portage was established. Although the trail isn’t evident, portions of the original portage can be followed today based on topography. The portage route at Jones Falls is still partially evident today since the original native route saw continued use during the building of the canal. None of these portages have ever been archaeologically investigated, so much more remains to be discovered.

During the building of the Rideau Canal, native people and those building the Rideau Canal can be best described as two solitudes – each group doing their own thing – one group continuing with traditional hunting and gathering, the other building a canal. The official reports are silent on the topic of native people, but we have a couple of very brief first hand accounts.

John McTaggart noted that a survey party he was on got lost in the drowned lands north of Upper Brewers. At that time (1827), mill dams (Morton & Round Tail) had flooded the forested areas of the Cataraqui Flood Plain. They were travelling through acres of dead trees. They got lost and had to overnight on the shore. While trying to find a way out the next morning “… we heard the report of a musket at a distance. We bore away to the place whence the sound proceeded, heard another shot let off, and even saw the smoke. It was an Indian shooting wild ducks. We all felt rejoiced to see him, divided the drop of brandy, engaged him as a guide, and he brought us out at the famous Round Tail mouth of the Cataraque ...” (from Three Years in Canada by John McTaggart).

We also have an account, written by Hugh Macgregor, who travelled with Colonel By on the first steamboat trip along the Rideau in 1832. He stated (on about May 23, 1832) “It was with great pleasure that on passing through Indian Lake, after leaving Chaffey's Mills, we beheld a party of Indians drawn up rank and file on the beach in front of their encampment, having two Chiefs, and Union flags floating among the dark green foliage of the clustering pines. On our approach, they saluted the boat with a feu de joie in most regular order, and in a style that would not discredit a regularly organized corps. We immediately returned the compliment by firing a cannon several times and making a sheer out of the direct course, passed in front of the encampment, when Col. By received them on board to the number of about 40 men, women and children, who went on to the Isthmus with us, their boats and canoes towed astern of the steamer, ten in number - here we were again received with shouts of applause, from a numerous body of people, ready on the rock to receive us, Captain Cole and lady of the number, several firing guns, which we returned by firing the cannon, and a feu de joie, fired by the Indians who stationed themselves on the wings of the boat.” (Kingston Chronicle, June 9, 1832)

Native use declined over the years as land along the Rideau Canal became developed and native hunting and gathering opportunities diminished. The early canal records show many instances of “passing Indian canoes” but these dwindle over time until the era of native hunting and gathering in this area ended.

|

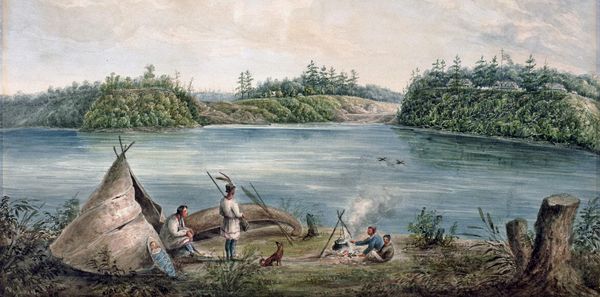

Native Camp on the Ottawa River in 1833

across from the new Rideau Canal

This camp was located near where the Canadian Museum of History sits today. Entrance valley

and Barrack Hill (now Parliament Hill) are visible across the river (right side of painting). "Entrance

of the Rideau Canal, Ottawa River, Canada" by Henry Pooley, 1833. National Gallery of Canada. Note: the artist of this piece, Henry Pooley, was one of the Royal Engineers that served during the building of the Rideau Canal.

|

-Ken W. Watson

|