Your location: Rideau Canal Home Page > Articles of Interest > Those Who Laboured

THOSE WHO LABOURED

by

Ken W. Watson

Note: This article first appeared in the Fall 2003 edition of Rideau Reflections, the newsletter of the Friends of the Rideau (www.rideaufriends.com).

The Rideau Canal is not only a engineering marvel, it is a tribute to human sweat and toil. The construction involved thousands of labourers who battled difficult working conditions and diseases such as malaria. Many died during the building of the canal. Unfortunately there are few detailed records, so any article about those who laboured to build the canal is an opinion piece. But enough information survives to put together a reasonable picture.

It was decided in 1826 that the Rideau would be constructed by independent contractors. The superintending engineer of the project, Lt. Colonel John By of the Royal Engineers, divided the canal into 23 sections, ranging in length from 3 km to 47 km, each with its own contractor. These included well-established contractors such as John Redpath, Philemon Wright, Thomas McKay, and Robert Drummond. It also included many who were new to the contracting business, taking advantage of the opportunity provided by such a large construction project.

Although Colonel By brought in two companies of Sappers and Miners (soldiers skilled in such crafts as masonry, carpentry and smithing), totalling 162 men, these were primarily used as peacekeepers, guards and overseers. There were skilled jobs involved in the construction, such as stone masons, carpenters, quarriers and blacksmiths. However, the bulk of the work called for men using picks, shovels and axes. Forests had to be cleared, lockworks excavated, canal channels dug. The location of the Rideau, in the middle of the Canadian wilderness, crossing through swamps, dense forests and the rocky terrain of the Canadian Shield, precluded the use the primitive steam powered equipment of the day, so everything had to be done by hand with some limited aid from draft animals. An estimate at the beginning of the project stated that 1,000 craftsmen and 4,000 labourers would be required to complete the project.

Several of the established contractors had ready labour forces in waiting – these were mainly French Canadians who worked in timber camps in the region. These men were used to this type of hard manual labour. Most of the timber camp work was done in the winter, so this labour force was free to work on the canal during the summer. There was also a downturn in the timber trade at this time, and many French Canadians from Lower Canada came seeking work on the Rideau. The other component of the labour force were new immigrants to the country. Most of these were Irish.

In 1827, at the start of the main construction of the canal, there was a surplus of Irish immigrants looking for wage work. The textile industry has collapsed in Ireland, leaving many Irish families destitute. Canada became a destination of choice. One of the few surviving documents of the period is the McCabe list, an 1829 petition, signed by 673 men, mostly Irish, many of whom were working on the canal. It showed that three in five had families with them in Canada and that many were Protestant Irish.

|

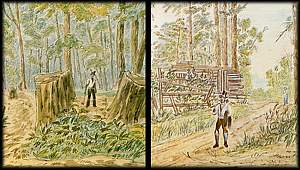

| Left = French Canadian axeman. Right = Irish labourer. Both men are in typical garb, the French Canadian in a toque, shirt, trousers and moccasins – the Irishman in breeches, knee stockings, simple shirt and stovepipe hat. Illustrations are sections from two of J.P. Cockburn’s Rideau watercolours, dated August, 1830 (from Passfield). |

The condition of the Irish immigrants was often quite poor. Colonel By, writing in April of 1827 stated “I therefore expect to collect a great number of persons on the Works by the first May and fear from the wretched condition of most of the emigrants applying to me for work, that it will indispensable necessary to issue bedding to prevent sickness … at present the poor fellows lay with nothing but their rags to cover them, and their numbers are increasing, and the rainy season coming on, I dread the effects of Sickness and feel convinced that the distribution of bedding will be of the greatest importance.”

Dr. David Shanahan, in his fascinating talk at the Friends of the Rideau AGM this past Spring, spoke about the culture of these Irish immigrants in Canada, noting that these were a people in a completely foreign environment. The British North America culture was different, mosquitoes and blackflies were a new (and terrifying) experience and the prevalence of malaria in North America was just one of several deadly diseases that could kill or cripple. In the class structure of the day, the Irish were near the bottom of the totem. So although they have sometimes been classified as an unruly rabble, many of their actions are understandable in the context of trying to survive, and maintain their culture, in a strange new land.

The most complete description of a “typical” canal work camp during the construction of the Rideau is perhaps that at Newboro. William Hartwell was contracted in July of 1827 to “To Excavate and form part of the Rideau Canal between Rideau Lake and Mud Lake …” This would turn out to be one of the most difficult sections of the canal. Hartwell’s contract terminated in about November 1828 when he was forced to abandon the site due to excessive costs. At this time there was an assessment of the buildings on the worksite. They included a large barn, a long stable, a mill house, a carpenter’s house, a smithy, a store and six large shanties. These shanties were 20 feet by 20 feet in size. This is where the workers lived and slept.

An exact description of these particular buildings is not available, but it is assumed that the shanties were similar to lumber shanties of the day – a log building, with a peaked roof, a hearth in the centre of the floor with an opening directly above it, a door at one or both ends, no windows, and bunk beds running along the sides. There were few provisions made for families – many families lived in “shanty towns” in the growing communities of Bytown and Kingston, with a few living near the construction sites in home-built shanties (a log cabin, higher in the front than the back providing for a single sloping roof). In some camps, women were employed for domestic tasks and boys were employed in jobs such as the carrying of provisions.

The work was brutally hard. During the summer work went on for fourteen hours a day, six days a week. Although the Irish took well to pick and shovel work, the chopping of trees involved a long and very painful learning curve. Many excavations were cleared with the aid of wheelbarrows, the labourers pushing them uphill along “barrow runs.” In areas where rock excavation required the use of explosives, several workmen died working with the unstable “merchant powder” (nitre, sulphur and charcoal). Given the nature of the work, there were also accidents involving rock falls and drownings. But the single biggest killer was disease, primarily malaria, the temperate form (Plasmodium Vivax) that existed in North America at that time.

Malaria was indiscriminate - men, women and children all died from it. Some of the contractors, local residents, and several of the Sappers and Miners were struck down by this disease. Even Colonel By came very close to dying from it. But the brunt was taken by the largest component of the work force, the labourers. The close working and living conditions of the men made for ideal transmission of the disease.

It is uncertain how many men died building the Rideau. The records are incomplete, we will never know for sure. The memorial to the workers in Kingston states that “an estimated one thousand” died, and this is as good a number as any. Previous estimates have pegged a number of about 500 deaths from malaria alone – the remainder would have died from other diseases and work related accidents.

We don’t even know what percentage of the workforce this was, since we don’t know the size of the workforce. It is estimated that on an annual basis from 2,500 to 4,000 people worked on the canal, but the estimates of the total over the period 1826-1832, taking into account death and employee turnover, vary from 4,000 up to about 10,000.

The exact numbers are not relevant – it should simply be remembered that a great deal of human sweat, toil and death went into the construction of this amazing canal. Their efforts and sacrifice should not be forgotten.

- Ken Watson

|

Remembering the Workers

On November 23, 2002, a Celtic Cross, located in Douglas R. Fluhrer Park in Kingston, was unveiled and blessed during an interdenominational service. The inscription on the cross states “In memory of an estimated one thousand Irish labourers and their co-workers who died of malaria and by accidents in terrible working conditions while building the Rideau Canal, 1826-1832.” On November 23, 2002, a Celtic Cross, located in Douglas R. Fluhrer Park in Kingston, was unveiled and blessed during an interdenominational service. The inscription on the cross states “In memory of an estimated one thousand Irish labourers and their co-workers who died of malaria and by accidents in terrible working conditions while building the Rideau Canal, 1826-1832.”

The cross project was initiated to remember the many labourers who died building the canal. Definitive records do not exist, but the 1000 estimate is a reasonable guess. Approximately half to two-thirds of the labour force that built the Rideau Canal were immigrant Irish. Most of the deaths were a result of disease, principally malaria that ravaged the southern working areas during the years 1827 to 1831. There were also workplace deaths, a result of such things as black powder blasting accidents, rock falls and drownings.

A second cross was unveiled in Ottawa in 2004. For a view of all the various memorials along the Rideau Canal see the Memorials and Markers Page.

|

Back to Rideau Articles Page Go to Top of This Page

Comments: send me email: Ken Watson

©1996- Ken W. Watson

|