Rideau Contractors

by

Ken W. Watson

Note: This article first appeared in the Spring/Summer 2021 edition of Rideau Reflections, the newsletter of the Friends of the Rideau (www.rideaufriends.com).

| |

|

| |

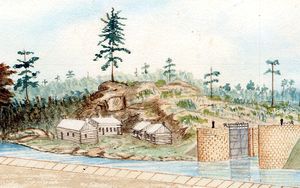

Jones Falls - 1831 and TodayThe painting shows the construction camp for the locks at Jones Falls built by contractor John Redpath to house and feed the tradesmen and labourers. Bottom is that same location today with the 1843 Blacksmith’s Shop on the site. Parks Canada has never done any research or archaeological work here, so we don’t know much about the original camp other than the 1831 painting. “Bason & Upper Lock at Jones' Falls; from the East Upper end of 3rd Lock. Works nearly completed”, by Thomas Burrowes, October 1831. Archives of Ontario, C 1-0-0-0-55.

Photo by: Ken W. Watson |

The Rideau has recently seen significant infrastructure work to rehabilitate many locks and dams on the Rideau Canal that have been allowed to deteriorate over the years. This work has been done by contractors with their work supervised by government engineers. This is how the Rideau was originally built, the work done by contractors supervised by government engineers, British Royal Engineers. The decision to build the Rideau Canal using contractors was made before Lt. Colonel John By was appointed the Superintending Engineer for the project.

In 1825, the Duke of Wellington, who at that time was the Master General of Ordnance, tasked Royal Engineer Major General James Carmichael Smyth with investigating the defense of Canada. Wellington was a strong proponent of the Rideau Canal and Smyth’s report confirmed the Rideau Canal as a critical component of Canada’s military defense. Smyth left three main legacies – his report confirmed the need for a Rideau Canal; he put forward an unrealistic low estimate of £169,000 to build the canal (based on surveyor Samuel Clowes’ estimates), and he recommended the canal be built by contractors. In March 1826 Smyth wrote a memorandum to General Mann (Inspector-General of Fortifications) which read in part, “I am of the opinion that it will be found more economical and more expeditious to execute the greatest part, if not the whole, of the proposed Rideau Canal by contract …”

At that time the Grenville Canal (Ottawa River) was being built by the Royal Staff Corps (a military engineering branch of the British Army) who were directly supervising the hundreds of French-Canadian and Irish labourers who were building that canal. But the Rideau would be different, it would be the contractors responsible for the construction, hiring their own crews and building the locks and dams to the specifications of the Royal Engineers. A number of checks were put in place to mitigate anticipated problems. Colonel By insisted that no contractor be given more work than he was capable of completing in a two year period. So he divided the canal construction into 23 sections, ranging in length from 1 ¾ miles to 29 ¼ miles (3 km to 47 km), each with its own contractor. Royal Engineers were stationed along the line of the canal to directly supervise the work. To avoid potential labour issues, the Commissariat (supply and services division) made it a requirement that workers be paid in cash (silver coins) and that contractors would not be paid unless it was confirmed their labourers had been paid.

The financing of the project, by yearly Parliamentary grants, didn’t work well with a contracted job. You can’t simply start and stop contracted work and so By’s superiors in Ordnance instructed him to do the work needed to build the canal, regardless of the Parliamentary grants. This was to lead to troubles for By and his legacy. By’s lobby for larger locks also caused him problems. Smyth recommended locks 108 feet long by 20 feet wide with a depth of 5 feet. Colonel By, anticipating the military steamboats of the day, lobbied for the locks to be 150 feet long by 50 feet wide by 10 feet deep (he later modified the depth to 5 feet to make his proposal more saleable). In early 1828, a commission was set up under Lt. General Sir James Kempt to investigate the issue. In June 1828 it recommended the locks be 134 feet long by 33 feet wide by 5 feet deep. Existing work on the smaller size locks had to be torn down, re-engineered and rebuilt.

The contractors themselves had mixed backgrounds. Colonel By noted “the Dam at the Hog’s Back and that at Smith’s Falls were the first commenced; at which time there was not a man in the country that had ever done any key [stone] work, and I had repeatedly to pull down their work until they understood it, but as there are now plenty of men who understand this work I hope all my other Dams will stand the test of ages.” While perhaps true in terms of dam building, he did have a few contractors who were very familiar with stone work. Two of those, John Redpath and Thomas McKay, are well know today since they went on to become businessmen of prominence in Montreal and Ottawa.

| |

|

| |

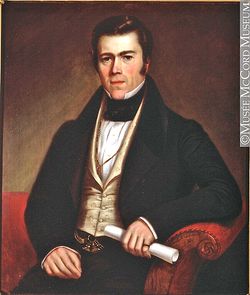

John Redpath in 1836Perhaps most famously known as the founder of Redpath Sugar in Montreal, Redpath was a skilled masonry contractor. In a December 1831 letter, he expressed some regret at having taken the job due to the problems with malaria at the site (he came down with it 3 times). But in 1834, he moved his family to Jones Falls (where his sister was still living) as a healthier place than Montreal due to the cholera outbreak that killed his wife. Painting by Antoine Plamondon, 1836. Gifted to McGill by Miss Jean Bovey and held by the McCord Museum in Montreal.

|

Another two, Andrew White and Thomas Phillips, while lesser known today, were also skilled at masonry. All had prior masonry experience in Montreal. But there were a host of contractors whose names are not familiar to most today, such as Donald McLever (Davis Lock), Edward Thompson (Kilmarnock) and A.C. Stevens (Merrickville and Nicholsons). In fact with the latter, we (I) don’t even know his first name (if someone does please send me an email).

Colonel By fired at least one contractor, James Clowes, who was contracted for Clowes dam and lock. By stated “contracted for by Mr. James Clowes who has cut a large quantity of good stone for the Locks, and commenced the Dam, but in so unworkmanlike a manner, that I broke his contract on the 13th Instant [January 1828], Capt. Savage, Capt. Victor & myself being of the opinion he had not ability to conduct such a work.”

About half the contractors made good money, the other half quit or went bankrupt – in part due to the difficulty of the site they were working on, but mostly due to their skills, or lack thereof, as good project managers and businessmen. William Hartwell at Newboro asked to be released from his contract due to difficulties with the hard bedrock and problems with malaria at that site. Walter Fenlon, who most famously was the contractor for Hogs Back, begged to be released from his contract after the dam he was building there got washed away, twice. On June 18, 1828, he wrote to Colonel By: “I find that I cannot possibly continue the Work at the prices that I am at present getting according to my Contract and I am the looser [sic] to a great amount on what I have already done. My humble prayer at this time, is, that Government would take the job and release me from all claims on the Contract. I trust I shall be allowed an estimate on what I have done in preparation for carrying on the work, and my losses I submit to the Consideration and discretion of the Commanding Officer.”

At least two contractors died on the job. Samuel Clowes (who surveyed the Rideau in 1823 & 24) at Lower Brewers and John Sheriff at Chaffeys both died, reportedly from malaria. A few contractors went bankrupt, such as John Brewer at Upper Brewers who fled to the U.S. in 1831 with, as the story goes, “his creditors at his heels.” Some did better than expected, such as Robert Drummond the contractor for Kingston Mills, who was a very savvy businessman. He took over the job at Lower Brewers in late 1828 after Clowes died, he took over Upper Brewers in 1831 after John Brewer left (at a price 40% higher than what John Brewer had contracted the job for) and he also took over the work at Davis Lock after McLever went bankrupt in 1829, forming a partnership with the remaining contractor at Chaffeys, John G. Haggart (Sheriff’s partner).

The story of the contractors is a complicated one that has never been fully told. For those interested, you will find the names of the contractors, plus transcripts of two Rideau contracts (Fenlon’s contract for Hogs Back and Rykert, Simpson & Adams’ contract for Smiths Falls) in my book “A History of the Rideau Lockstations” published by Friends of the Rideau. It is also available on-line here.

-Ken W. Watson

|