Women at the Rideau Worksites

by

Ken W. Watson

Note: This article first appeared in the Spring/Summer 2015 edition of Rideau Reflections, the newsletter of the Friends of the Rideau (www.rideaufriends.com).

One of the great untold stories of the Rideau Canal is the life of women and children at the worksites during the building of the canal. We tend to think of the worksites as male only, labourers and craftsmen building the mammoth works of the Rideau Canal. But that's not an accurate picture. Many of the men were married and had their families with them at the worksites. But how many women were at each site and their exact roles remain frustratingly vague.

|

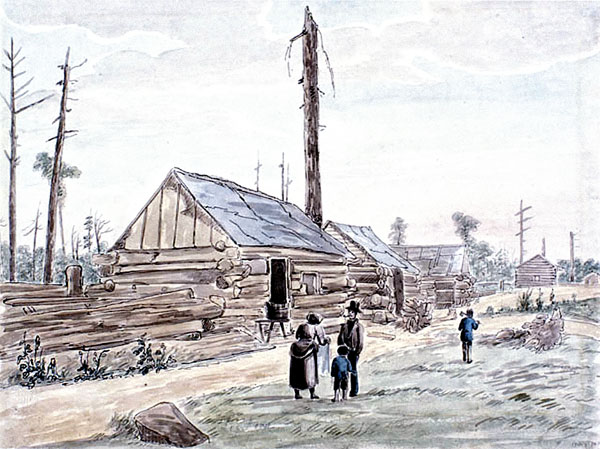

Family at Long Island, 1830

This painting shows an Irish family and a group of log cabins at Long Island. The men were part of the workforce building the locks, dam and weir at Long Island. “Settlement on Long Island on the Rideau River, Upper Canada” by James Pattison Cockburn, August 17, 1830, Library and Archives Canada, C-040048

|

The problem is the inherent bias in the historical records. The bulk of the Rideau Canal documentation are basic bureaucratic material such as progress and accounting reports. These reports don't mention the daily life of the worksite, they detail issues directly related to the building of the canal. However we do have a few reports concerning sickness and death which provide some insights about the presence of women at the worksites.

A.J. Christie's 1827 medical reports for the Rideau worksites show that 17 men died (10 from disease, 7 from accidents) as well as 6 women and 38 children. He also recorded 54 births. So we clearly have many families at the worksites. With the first outbreaks of malaria in 1828, Colonel By began to compile sick reports. For instance, at Jones Falls in 1828, 2 men died but no women or children died, whereas in 1830 at Kingston Mills, 8 men died along with 4 women and 4 children. That's a clue regarding where many families were located. Jones Falls had a labour force taken from Quebec (mostly Montreal), primarily French-Canadian and Scot. Most of their families would have been left back home. Kingston Mills, on the other hand, had many recently immigrated Irish workers and their families living on the worksite. A November 1830 census at Kingston Mills shows 101 buildings located on the site, including a schoolhouse.

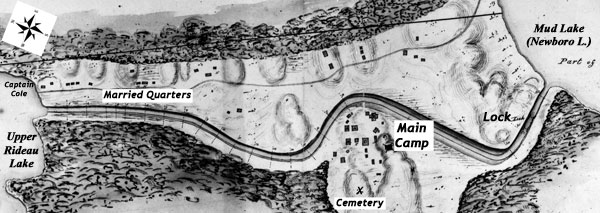

Many of the Royal Sappers and Miners were married. In 1831 for example, there were 51 men of the 7th Company located on the Isthmus (Newboro) together with 27 women and 46 children. An 1830 map of Newboro shows the single men's barracks and the civilian barracks located in the main camp and houses for married sappers and clerks in a separate area (see map on page 2). In 1829 at Hartwells, records show the employment of 25 military personnel, 482 civilian labourers and 83 boys. There is also a reference to gangs of boys hauling water at Hogs Back. The presence of boys indicates families living near the site. The 1830 painting by James Cockburn (above) shows a number of cabins at Long Island with families living in them. We also know that several of the contractors and craftsmen had their families with them.

So these are some of the indications that women were present at many worksites, but what role did they play? With no actual documentation we can only assume that they played the typical domestic role of that era centred around raising a family. There is much written about how tough the men had it, but it was also very tough on the women. They were in a rough frontier, trying to raise a family with limited support. The women were responsible for managing the household and their ever growing family of young children. Their days were spent caring for their children, preparing meals, cleaning and doing laundry, making and mending clothes, and tending to the sick. They had to make do with what they had, which was very little. Unlike settlers (who also had it tough) they had no land. The husband was working for wages in the hopes of saving enough for a better future for their children.

Christie in his 1827 medical reports noted that many of the women and children, as well as many men, were suffering from digestive problems (bowel complaints). He surmised, likely correctly, that it was due in part to the severe change in diet from a vegetable-based diet to a meat-based diet. It was also likely due to a lack of understanding of sanitation – e-coli and other bugs would have been present in some of the meat, vegetables and water. While some of the workers did start little garden plots by their cabins at the worksite, they were very reliant on supplies obtained by the contractor. Those supplies included flour, potatoes, bread, corn, bran, and peas. For meat the main staple was salt pork with some beef and pickled fish. Diet improved when local settlers started supplying the camps with fresh meat and produce. Workers’ families also gained local knowledge of plants that could be used to make teas and flavour stews.

The women would have relied on each other, particularly in the event of sickness and childbirth. Death and injury were facts of life, not only for the husband but also for the children. Many children died, buried in the local burying grounds, the wooden markers on their graves long ago rotted away. We do however know the names of two children who died in 1829 and are buried at McGuigan Cemetery near Merrickville; Francis Ivers Frayne, the 18 month old son of Master Mason Richard Frayne, and Margaret Davidson, the two year old daughter of the contractor at Clowes, who died from "a contusion in the head."

One thing we can assume is that many of the women would have put on a brave face and coped with conditions as best they could. One of my ancestors, Mary Quaife, who arrived in Canada in 1832 with husband James and 4 children (ages 6 months to 6 years) wrote: "I am quite at home in my little cottage, as I have a good bed and a seat to sit on which is as much as I expected to have in this land." Contrast her description of a "little cottage" with the reality of a small one room log cabin for a family of 6 (7 by the next year) on the edge of the woods in the Cornwall area, rented to them by a local farmer. They had no money and her husband was working for shares (a portion of the harvested crop).

The experiences of women at the worksites is a very difficult story to tell due to the dearth of information. Perhaps in the future someone will take this on as research project and do proper justice to the topic.

-Ken W. Watson

|

The Construction Site at Newboro in 1830

This annotated map shows the many buildings at the Newboro lock and cut construction site. The married Sappers and Miners and workers’ families lived in cabins on the east side of the cut. The cabins above the words Married Quarters are those shown in the legend as “House[s] for married sappers and clerks.” Also note the large swath of forest cut down on Colonel By’s orders to promote fresh air and blow away the bad air that caused (so they incorrectly thought) malaria. “Plan of the Isthmus Between Rideau and Mud-Lakes” by P. Cole & John By, 1830, Library and Archives Canada, NMC 12892 54/80.

|

|