Bye By

by Ken W. Watson

The Story of Lieutenant-Colonel John By, R.E. and his fall from grace.

It was 6 a.m. on May 25, 1832, when the sound of a cannon shot reverberated through the village of Smiths Falls. The sound roused a few from their beds, but most were already up, waiting anxiously for what that sound represented. They were gathered at Smiths Falls Detached Lock, braving the chill of early morning, in anticipation of the big event.

There was smoke on the horizon and the residents now caught sight of the paddle-wheel boat as it rounded the last corner and headed straight for the lock. It was a small cannon on board that boat that had announced its imminent arrival. Cheers erupted from the crowd as they recognized the unmistakable silhouette of a man standing at the bow of the boat; it was Lieutenant Colonel John By, Royal Engineer, the man in charge of building the Rideau Canal. On a promontory overlooking the village, the roar of an eighteen pound cannon drowned out the cheers of the crowd as a group of enthusiastic villagers fired a return salute to Colonel By.

At the very instant that Colonel By was being given an overwhelming welcome in Smiths Falls, thousands of miles away, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, a clerk was penning the instrument of Colonel By’s demise. He was writing down a minute [official memorandum] resulting from a meeting that morning of the Lord Commissioners of the British Treasury. He was just at the point of writing “they [Lords of the Treasury] cannot delay expressing their opinion to the Master General and Board of Ordnance on the conduct of Colonel By in carrying out this Work [the Rideau Canal].”

In Smiths Falls, the boat that Colonel By was travelling on was now being locked though Detached Lock. It was Robert Drummond’s 80 foot long steamboat, Rideau (aka Pumper) on the inaugural cruise through the Rideau Canal to mark its official opening. Colonel By stepped off the boat to greet the crowd. He was followed by his wife Esther and their daughters, 13 year-old Esther March By and 11 year-old Harriet Martha By. They walked along, chatting with the crowd, as the boat headed to Smiths Falls Combined Locks. As they arrived at Combined, the big gun on the hill fired another salute.

In London, the clerk was close to finishing up the minute. He dipped his pen and with fresh ink wrote, “They [Lords of the Treasury] desire, therefore, that the Master General and Board will take immediate steps for removing Colonel By from any further superintendance over any part of the Works for making Canal Communication in Canada.” The clerk was almost done. The document would be communicated to the Board of Ordnance and it was intended to be put before the House of Commons.

In Smiths Falls, Colonel By couldn’t help but feel a flush of pride as the Rideau was flawlessly locked through. The lock staff were performing their jobs with utmost efficiency. His work here was essentially complete. It seemed like ages ago that he took his first trip through the Rideau Route. That trip, in May 1827, was by birchbark canoe, with voyageurs paddling the craft through the Canadian wilderness, broken only by a few mills, a few settlers. To get from the Ottawa River to Kingston, the canoes had to be pulled up some rapids and portaged around others. Now those rushing waters had been turned into fine sheets of still water. Where there had been rapids, there were now dams and locks. In less than six years, By had succeeded in his mission, to create a navigable waterway suitable for steamboats, extending 202 km (125 miles) between the Ottawa River and Kingston. To achieve navigation, 47 masonry locks and 52 dams had been constructed.

Colonel By thought to the future; a promotion in rank certainly, a knighthood perhaps. He had worked tirelessly over the last six years in this service to the Crown, suffered many setbacks, endured bouts of sickness, but in the end he triumphed. The Rideau Canal, a feat of human creative genius, had been born.

Back in London the clerk was completing the minute, “My Lords further desire that Colonel By may be forthwith ordered to return to this country, that he may be called upon to afford such explanation as My Lords may consider necessary upon this important subject.” The subject at hand was that the expenditures for the building of the Rideau Canal had exceeded the amount allocated by Parliament. It was a time of parliamentary reform in England and of battles for control of the British treasury. Ordnance needed to be taught a lesson, an example had to be made, and the example chosen was Lieutenant Colonel John By.

The Colonel and his family stepped back on board the Rideau as it entered the lower lock at Combined. The water in the lock was lowered, the gates opened and grey billowing smoke spewed from the smokestack of the Rideau, as, with the boiler at full pressure, the 12 hp steam engine strained to turn the twin paddle-wheels. The ship left the lock and headed towards Old Slys. On the hill above town, the gun crew was readying the cannon for a last rousing salute to Colonel By. They crammed in 10 pounds of powder and then tamped sods of earth down the barrel. The cannon was primed and then the shot was fired. The cannon exploded — literally — the end of the barrel blasted apart. Pieces of metal travelled up to 425 feet (130 m) from the shattered cannon. Only four feet of the muzzle remained. Miraculously, no one was hurt in the incident.

Oblivious to the excitement of the exploding cannon, the Rideau steamed sedately towards Old Slys.

Oblivious to what was being written about him in London, Colonel By continued to enjoy his triumphant cruise. He wouldn’t receive the official notice of his recall until August.

A very brief biography of John By.

John By was born in either 1779, 1781 or 1783, the second surviving son of George By and his wife Mary, in Lambeth, across the River Thames from London. It was a middle-class home, his father was a senior officer in the London Customs House. The young By attended the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, graduating in 1799. He received a commission as Second Lieutenant in the Royal Artillery on August 1, 1799, but was transferred to the Royal Engineers on December 20 of that year. His further commissions were dated: Lieutenant, April 18, 1801; Second Captain, March 1, 1805; First Captain, June 24, 1809; Brevet Major June 23, 1814; and Lieutenant Colonel on December 2, 1824.

In 1801, he married Elizabeth Johnson Baines. In 1802, he was posted to Québec City (where one of his projects was constructing a detailed 1:300 scale model of Québec City with the help of draftsman Jean-Baptiste Duberger). In 1811, he was posted to Portugal. In 1812, he was back in England, placed in charge of the Royal Gunpowder Mills. His wife Elizabeth died in 1814 – there were no children from this marriage.

In 1818, John By remarried, to Esther March. In 1819, they bought Shernfold Park, an estate in Frant, southeast of London. Their first daughter, Esther March By, was born that year. In 1821, By (then Major By) was “retired” and placed on half-pay. Their second daughter, Harriet Martha By, was born that same year. On April 21, 1826, By was brought out of retirement and appointed Commanding Engineer for the Rideau Canal project.

|

|

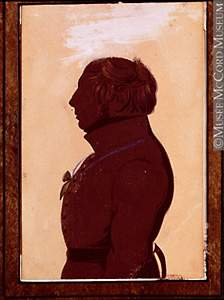

| Which image is the real John By?

The only (believed to be) authentic image of John By is the silhouette on the upper left, presented to John Redpath. It fits William Lett's description of By as being "portly." The image on the right is a face put on that original silhouette by an unknown artist. The two images below are artists renderings, the one of the left, by C.W. Jefferys, looks nothing like Colonel By, the one of the right, an idealized rather than authentic image of By. Upper Left = Colonel John By by unknown, c.1831, McCord Museum, M676. Upper Right = Lieut.-Col. John By, Royal Engineers, Founder of Bytown by unknown, c. 1891, Library and Archives Canada, C-28531. Lower left = Colonel By Watching the Building of the Rideau Canal, 1826 by C.W. Jefferys, c.1930, Library and Archives Canada, C-073703. Lower right = Colonel John By, Royal Engineers; 1830 by 'C.K.', n.d., Library and Archives Canada. |

The Problems with the cost of the Rideau Canal

By’s recall notice had its roots in a myriad of problems, some dating from before he was appointed Superintending Engineer for the Rideau Canal, before he was even aware of the project. Most of these problems related to how the canal was financed. The general protocol was for the Board of Ordnance (the engineering and fortifications branch of the military) to make annual requests to Parliament for the financing of various projects. A yearly spending authorization for each project was issued to Ordnance by Parliament. Ordnance was supposed to keep its spending within the amount authorized by Parliament each year.

The first problem was the initial cost estimate for the construction of the Rideau Canal, made by civil engineer Samuel Clowes in 1824. Clowes offered estimates for three sizes of canal. For his middle size, locks 80 feet long by 15 feet wide by 5 feet deep, he submitted an estimate of £145,802. When the project was approved in 1826, it was to be for locks 108 feet long by 20 feet wide. To compensate for the extra size, Major General Sir James Carmichael Smyth, an executive officer serving under the Duke of Wellington, simply added £500 per lock to Clowes’ estimate and came up with an estimate of £169,000. That number, which turned out to be unrealistically low, would continue to haunt Colonel By and the Ordnance Department, since it was the officially accepted number on which the decision to go ahead with the Rideau Canal project was made. So people got the mistaken idea that the canal should have cost about £169,000.

Colonel By himself never agreed to or supported the £169,000 estimate. An 1831 report from a Parliamentary Committee set up to investigate the expenditures noted “... on the 13th August [1826] and on the 6th December 1826, Colonel By, then in Canada, reported on the probable insufficiency of the sum proposed. ... Your Committee cannot refrain from expressing some surprize, that after such communications had been received, an Estimate of £169,000 for this Work should have been laid before The House in May 1827.” On November 1, 1827, Colonel By sent his first detailed cost estimate, which was for £474,844. While still low, it was a much more realistic starting number, based on the information available at the time, than £169,000.

A second problem also stemmed from Major General Sir James Carmichael Smyth, who appears to have been one of the first to recommend that the project be done by contract, rather than being done directly by the Board of Ordnance. It was actually a good decision from a logistics point of view and it improved the efficiency, speed and cost of construction. However, it created a large problem with the annual grant system in use by Parliament. The contracts were “per job,” (i.e. building a dam or lock), you couldn’t easily turn on and off the contracts based on the availability of annual Parliamentary grants.

A third problem was the distance between London and the Rideau. A decision made in London would take weeks to arrive on the Rideau. To get information from the Rideau to London, have a decision made, and then get that information sent back, often took months. For instance, Colonel By was ordered in 1828 not to release or extend any more contracts until the report from the Kempt Committee was finalized. But by the time Colonel By received this order in Bytown, he had already let and extended several contracts.

A fourth problem was the eventual cost of land acquisition. Early estimates for the canal didn’t take into account the cost of land. The project was rushed ahead so fast that there wasn’t time to quietly (cheaply) acquire the land needed for the canal. Plus the entire Rideau Route had already been land granted, so except for Crown and church reserves, it was all privately held. The Rideau Canal Act was passed in 1827, allowing land to be expropriated, with settlement to be made by arbitration after the canal was completed. That simply made it easier to acquire land, it didn’t make it any cheaper. By’s slackwater design meant drowning many acres of private land, all of which had to be paid for. Colonel By created an innovative lease-back system to mitigate the costs, but, in the end, the expense of land acquisition added greatly to the cost of the canal.

A fifth problem was the technical reality of building a canal at this location in Canada in that time period. Unlike an engineering project today, where everything can be figured out (and costed) to the last detail before the first ground is broken on a project, with the Rideau, they had to figure it out as they went along. Engineering the works had to be adapted to the conditions that they found. By’s reports are full of “deviations from the original plan” indicating that he found it “indispensably necessary” to make this or that change. Examples of these include the increase in the size of the locks and the change from overflow dams to non-overflow dams which necessitated the addition of waste water weirs. The realities of spring floods in the Rideau area made this latter change indispensably necessary, but this wasn’t known when the project was started. Clearly the members of Parliament had no idea of the conditions and technical challenges that Colonel By was facing to build a navigable waterway in this part of Canada.

Another significant problem was the perceived chain of command. Ordnance was a branch of the military services to the Crown (Army, Navy, Ordnance, Commissary). By, as a military officer, was tasked with the job of building a navigable military waterway between the Ottawa River and Kingston. He took orders from and reported to his superiors in Ordnance. The Ordnance Department dealt with Parliament for funding grants for various projects, such as the Rideau. Colonel By was ordered by Ordnance to push ahead with that project regardless of Parliamentary grants. That order was never rescinded. Somehow, in the end, Colonel By got blamed for defying Parliament rather than, as should have been the case, By’s superiors in Ordnance.

Colonel By also created some of his own problems when he sent in his first estimate for the construction costs to the Board of Ordnance. After fully reviewing the route, he submitted an estimate of £474,844 for the planned size of locks. At the same time he submitted a much more ambitious plan which included locks 150 feet long by 50 feet wide by 10 feet deep, suitable for steamboat navigation. Colonel By eventually reduced his proposed 10 foot depth of navigation to 5 feet and provided an estimate of £527,844 to build the canal on that scale. But his plan was still radical; he intended to build high dams to flood the rapids, creating a full slackwater system.

Colonel By compounded his problems by omitting to mention in his report that Clowes’ figures were far too low. To the Board of Ordnance, including the Duke of Wellington, it appeared that Colonel By was ignoring Clowes’ more traditional lower cost canal design in favour of his own radical, far higher cost steamboat/slackwater design. Colonel By had in fact rejected Clowes’ plan based on its costs, not simply on its traditional design. Digging canal cuts through hard Canadian bedrock, such as Clowes’ proposed, would be much slower and more expensive than By’s slackwater design. But Colonel By failed to communicate that information to the Board of Ordnance.

So the Board of Ordnance, thinking that Colonel By was simply trying to promote his own (very expensive) canal design, appointed the Bryce Commission, a group of senior officers of the Royal Engineers, to look into the matter. They were tasked with looking at By’s new design and cost estimates and comparing them to Clowes’ design and costs. They submitted their report to Ordnance on January 23, 1828. In that report they fully agreed with Colonel By – Clowes’ plan would be much more expensive than originally stated and By’s plan was the more practical and cost efficient design for the Rideau Route.

The issue of lock size was still up in the air, so Ordnance created the Kempt Committee, under Lieutenant General Sir James Kempt, to look into By’s proposed larger lock size. They arrived at Kingston on June 15, 1828, where they were met by Colonel By. By this time, Colonel By was increasing his cost estimates to include military buildings and the cost of land acquisition, items not considered in the original estimates. Colonel By estimated that these would add an additional £60,000 to the costs.

The Kempt Committee completed its report on June 28, 1828. Similar to the Bryce Commission, they agreed with By’s design plans for the canal. However, on the question of lock size, they reduced By’s requested 150 by 50 foot locks down to locks 134 feet long by 33 feet wide. This was considered sufficient to accommodate the military steamboats of the day, which were 108 feet long by 30 feet wide. The 134 foot long locks, with the room required for the upper breastwork and the inward swing of the lower gates, allowed a boat up to 111 feet long to be locked through. Colonel By then submitted a revised estimate of £576,757 for this size of lock. That estimate included the additional £60,000 for buildings and land acquisition.

Back in England, the Board of Ordnance requested £105,000 from Parliament for 1828. Colonel By was ordered to go slow in keeping with that number (this was the order he received late, after already letting several contracts). Colonel By did what he could: he let go many men hired directly by the Royal Engineers (mainly tradesmen tasked with ensuring that the exact engineering designs of the locks and dams were complied with by the contractors); and he requested that the contractors slow down their rate of work, offering to extend some contracts to compensate for the slow down. This was difficult for the contractors, whose profits depended in large part on the speedy completion of their contracts. So in the end, their work didn’t slow down, with the exception of having to wait for the larger lock size to be approved.

Colonel By submitted another estimate on March 30, 1830, which included an extra £83,714 to cover the cost of waste water weirs at all sites. The dams had originally been designed as overflow dams, but the realities of the Rideau and Cataraqui rivers in full spring flood precluded the full use of overflow dams and Colonel By now considered weirs to be “indispensably necessary.” In addition, difficulties, such as the failures of the Hogs Back dam, caused cost overruns on the 1828 estimate to the tune of about £30,000. Contractors were also quitting, due to construction difficulties including seasonal malaria at the southern lockstations, and the re-contracting of these jobs had to be done at higher rates.

Throughout the construction period, Colonel By was submitting reports to his superiors in Ordnance, detailing changes that had to be made to the original plan and the extra costs involved in those changes. Colonel By was being completely transparent with the costs, Ordnance was fully aware of the actual costs of construction and why those costs were being incurred. Colonel By had submitted a revised estimate of £762,679 which included defensive structures recommended by the Kempt Committee. Ordnance decided to delay the defence works, and submitted an estimate of £693,448 to Treasury. This number was approved by Parliament. Up until the fall of 1830 there don’t seem to have been that many issues with costs other than technical issues (i.e. Bryce Commission, Kempt Committee). Colonel By was faithfully reporting all costs and changes to the cost estimates to his superiors in Ordnance. Parliament had been approving those cost increases. Then the government of Britain changed.

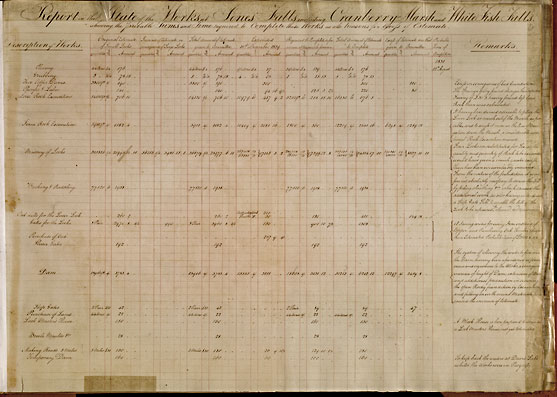

|

| Detailed Estimates

By detailed all his estimates, including all the changes from previous estimates and the reasons why, in reports sent regularly to his superiors in the Ordnance Department. Report of the State of the Works at Jones Falls including Cranberry Marsh and White Fish Falls shewing the probable Sums and Times required to complete these Works as also Reasons for Excess of Estimates by John By, c.1830, Library and Archives Canada, R11309-31-4-E |

Why Parliament Blamed By

In November 1830, a Reform government was voted in, a government that was opposed to large scale spending for the defence of the colonies, including Canada. If this government had been in power in 1826, the Rideau Canal would never have been constructed.

In March 1831, when the issue of the Rideau Canal was put before Parliament, a committee was set up to investigate the matter. They held two days of hearings on March 21 and 24. They called several witnesses, including Lt. Col. Edward Fanshaw of the Royal Engineers, who had served on the Kempt Committee, and Major General Sir Alexander Bryce. A wide range of topics was covered, from why the Rideau Canal was needed in the first place, to detailed analyses of the various cost increases. The Rt. Hon. Robert Wilmot Horton, Under Secretary of State, detailed the issue of authority, including the recommendation to proceed with the project without waiting for the Parliamentary grants, and the impossibility of working within the confines of annual Parliamentary grants using the contract system. He noted that “Colonel By is a servant of the Ordnance Department” and that the responsibility for the cost estimates rested with the Board of Ordnance. Somehow those facts appear to have been lost on Treasury and Parliament.

Another incident was now taking place in Bytown that would further cloud Colonel By’s reputation. A clerk in the Royal Engineer’s office, Henry Howard Burgess, dismissed in March 1830, for “negligence of duty,” now formally accused Colonel By of inappropriate use of public funds [see the section “The Henry Howard Burgess Affair” for full details]. Burgess, who had problems with alcohol and an erratic temperament, demanded that he be paid to the end of his contract period (August 1831). It was some months after he was turned down on that request that he threatened to go public with allegations that Colonel By has misspent public funds, and when he was turned down again, he made good on that threat. Eventually a court of inquiry was held, under Colonel Gustavus Nicolls, in which all of Burgess’ charges were reviewed in detail. The court fully exonerated Colonel By, but the whole affair added to the “taint” that Colonel By was acquiring.

Returning to the main issue of the expenditures for construction of the Rideau Canal relative to the amount of grants authorized by Parliament, in July 1831, as a result of recommendations from this committee, Parliament passed regulations that limited Ordnance spending to the amount of the annual Parliamentary grants. This included rules that all estimates be submitted for Parliamentary approval prior to the start of construction and that the total of all contracts must stay within the limit of the Parliamentary grant. This was the first time that these rules had been clearly defined. However, Ordnance failed to convey information about these new regulations to Colonel By, who was still proceeding with his orders to complete the canal with all speed and economy.

On February 23, 1832, Colonel By submitted his final estimate for the construction of the Rideau Canal. It totalled £803,774, which was made up of £715,408 spent to December 31, 1831, £46,615 required to complete canal construction, £14,000 for the purchase of additional required land, £7,750 for blockhouses and £20,000 as an estimate of compensation for land expropriated under the Rideau Canal Act. The recall notice drafted by Treasury on May 25, 1832, was based on these figures.

There was obviously a lot of political manoeuvring going on and somehow the Board of Ordnance was able to sidestep the blame for exceeding the Parliamentary grants. The Treasury Minute doesn’t blame Ordnance, it specifically blames John By. In fact they used By’s own detailed cost estimates, which he had sent to Ordnance, against him. Colonel By didn’t wilfully defy Parliament, but that’s what the Minute alleges.

Colonel By received his actual recall from Ordnance on August 11, 1832. He didn’t know at that time that it was Parliament that had asked for his removal and recall, as he was never shown the Treasury Minute. When he arrived back in England in late November 1832, he submitted the final costs of the Rideau Canal to August 31, 1832, a total of £777,146. He also included his estimate of £20,000 for expropriated land. As stipulated by the Rideau Canal Act, settlement for expropriated land was to be made after the canal was completed. This took until January 1834 to complete, and these land settlements increased the costs to the final number of £822,804.

Colonel By never got the chance to stand before Parliament to defend himself. On June 15, 1832, while Colonel By was still in Canada, a Parliamentary committee in London heard testimony from several individuals including Colonel Durnford, Commanding Engineer of the Royal Engineers in Canada, and William Sargent, Superintendent of the Commissary Department. That seems to have been the last official hearing into the matter.

Colonel By handed command of the Rideau Canal over to Captain Bolton on September 1, 1832, and later that month, together with his family, voyaged from Bytown to Québec City. He set sail from Québec City aboard the troopship Brothers on October 21 and arrived in Chatham, England on November 25, 1832.

Back in England

By’s military career ended when he set foot back on English soil. He seems to have essentially been abandoned; everything was left up in the air. The Board of Ordnance hadn’t fully defended By, since to do so would have put the blame for exceeding Parliamentary grants on their shoulders. The various Parliamentary hearings and internal reviews by Ordnance had fully exonerated Colonel By – he had done his job properly and had been completely transparent with the costs, continually submitting detailed estimates to Ordnance. But he had become a pariah, the Treasury Minute had been published in the papers, and his public image was tarnished.

The Reform government now in power opposed the Rideau project and it had singled out Colonel By as a example of the problems with the previous government. To them, Colonel By was a representation of the problem of power vested with the Crown rather than with the people. It really had little to do with the actual project – it was politics. If a full inquiry had been held on By’s return, he would have been publicly exonerated and the Board of Ordnance would, correctly, have been assigned the blame for defying the wishes of Parliament. But such an inquiry was never held.

Colonel By was clearly puzzled by what had happened. He hadn’t done any wrong, he’d pursued his duty with indefatigable zeal. Overcoming incredible obstacles he’d succeeded in creating one of the greatest engineering triumphs in the British Empire. But no one was coming out to support him. The accolades and rewards, which should have been his, didn’t appear. He quietly retired to his estate in Frant, Sussex, England.

He stayed busy, both with local affairs in Frant and with the Rideau Canal. He continued correspondence with the Board of Ordnance and the Royal Engineers, mostly on technical subjects dealing with the Rideau Canal. Colonel By was still the expert when it came to the canal and his advice on many matters was being solicited.

He also wrote letters to various people trying to get his name cleared. On January 23, 1833, he wrote a letter to his old boss, Colonel Durnford of the Royal Engineers. In it he explained his problems. Firstly, that the Treasury Minute [see pg. 82] which specifically named By, had only been seen by Colonel By in Canadian newspapers which had been sent to him. He goes on to say that “[I] feel extremely ill-used that the said minute was not sent officially to me, that I might have the opportunity of defending my character” and that “The present government appears to throw blame on me for not waiting for Parliamentary grants; forgetting that it was ordered by his grace the Master-General and Board [of Ordnance], that I was not to wait for Parliamentary grants, but to proceed with all dispatch consistent with economy, and the contracts were formed by the commissary-general at Montreal accordingly: by which the Engineer Department was bound to pay for the works as they progressed, which precluded the possibility of stopping the works without laying the government open to pay heavy damages [lawsuits] for so doing.”

Durnford did write a letter to General Pilkington – then Inspector General of Fortifications, on February 28, 1833, with a somewhat rambling defence of By. In it he stated that “The principle source of Lieut. Col. By’s present discomfort arises from the apprehension that, without some certificate or testimony, equally public, is afforded him, that the censure of the committee of the House of Commons [will remain].” Durnford goes on to note that anyone seeing the Rideau Canal, and the state of the country through which it was built, would conclude that “the outlay of money would not be wondered at, or given unwillingly, as a record of British ability and munificence.” Durnford also correctly notes that much of the extra costs were for land acquisition, not for the actual construction of the canal, and that these costs could not have been foreseen. As far as we know, Pilkington didn’t do anything in support of Colonel By – Pilkington was to die on July 6, 1834.

What did Colonel By expect in terms of recognition? Clearly the first thing he wanted was to have his named cleared in public. On a personal level, he certainly thought that he should have received some military honour. In a letter written on February 26, 1833, he noted his desire to be made “a King’s A.D.C., for the sake of the rank.” The King had the power to appoint aides-de-camp and, in the military, it would have conveyed the rank of full Colonel on Lieutenant Colonel By.

On July 22, 1833, he wrote to Major General Pilkington, Inspector General of Fortifications, with a request that “I may be honored with some public distinction as will show that my character as a soldier is without stain, and that I have not lost the confidence or good opinion of my Government.”

He never got that or any other honour before his death on February 1, 1836. He suffered his first stroke in October 1834, but it was a major stroke on January 29, 1836, that did him in. He died three days later. He was buried in the cemetery of St. Alban’s Church in Frant.

A memorial, erected by his wife Esther in St. Alban’s Church, reads:

Sacred to the memory of

Lieutenant Colonel John By, Royal Engineers

of Shernfold Park in this parish.

Zealous and distinguished in his profession,

tender and affectionate as a husband and a father,

and lamented by the poor, he resigned his soul to his Maker,

in a full reliance on the merits of his blessed Redeemer,

on 1st. February 1836, aged 53 years,

after a long and painful illness,

brought on by his indefatigable zeal and devotion in the service

of his King and Country, in Upper Canada

His wife Esther (b.1797), died in February 1838. His youngest daughter, Harriet Martha (b.1821), died in 1842. His eldest daughter, Esther March (b.1819), married Percy Ashburnham in August 1838 and died 10 years later in February 1848. They had two daughters, who both died as young children. John By’s older brother, George, died without issue in 1840. His younger brother, Henry, married and had two children. Henry died in 1852, pre-deceased by his sons who had both died, without issue, by 1847. So by the mid-1800s, there were no family members left to remember and promote the incredible achievement of John By.

By’s Vindication

It took a long time for Colonel By to be fully vindicated. It really only happened in the 20th century, as historians and researchers pored over the mountains of documents relating to the construction of the Rideau Canal. As they looked at the actual evidence, it became very clear what a monumental task the building of the Rideau Canal was, and what a significant role was played by Lieutenant Colonel John By, both in designing the works and in managing this huge project. High quality research by eminent historians such as Dr. Robert Legget and Robert Passfield led to the inevitable conclusion that Colonel By was poorly done by, and the records and physical evidence clearly show that Colonel By did a phenomenal job in service both to Britain and to Canada.

This same research also proves that Colonel By did build the Rideau Canal with economy. He didn’t waste government money, he did everything in his power to construct the Rideau Canal as economically as possible, while still meeting full engineering requirements. He followed the orders of his superiors in Ordnance faithfully and did not wilfully defy Parliament.

Passfield points out that the cost overruns for the Rideau were modest compared to other projects of the day. The Rideau cost 42.6% more than By’s June 1828 estimate (when the final lock size was determined), and only 18.6% higher than his March 1830 estimate which was accepted by Parliament. By contrast, the Ottawa (Grenville) canals took 15 years to build with a cost overrun of 60%. The Welland Canal took 10 years with a cost overrun of 55%. The Caledonian Canal in Scotland (which the Rideau is twinned with), took 19 years to build with a cost overrun of 87.6%. If Colonel By had kept within the yearly Parliamentary grants, the Rideau would have taken longer to complete and would have had far higher cost overruns.

Although this story isn’t an academic dissertation about the issue, for the sake of balance it should be noted that one historian isn’t a fan of Colonel By. George Raudzens argues in his 1979 book “The British Ordnance Department and Canada’s Canals 1815-1855” (based on his 1970 thesis at Yale), that Colonel By was the wrong man for the job.

According to Raudzens “Colonel By finished the Rideau Canal between June 1828 and May 1832 with money which he extracted from the British taxpayer’s pocket despite the House of Commons.” Presumably the right man for the job would have been someone who built the canal to the original small lock specifications, within the original £169,000 budget. A detailed look at the required engineering of the Rideau and actual expenses show that, even following the original design and lock specifications, it couldn’t have been built for anywhere close to £169,000. The Grenville Canal is a good example of a project that followed such “proper protocol” – it took a very long time to build (1819-1833), went way over budget (by 60%) and ended up costing almost £200,000 for a 9.6 km (6 mi.) canal cut and 7 locks.

Raudzens says that Colonel By had too much autonomy, noting what “a minor imperial proconsul could do by exploiting a defective system of colonial administration.” It is true that By, as a Royal Engineer, had his own vision of how to do the job right and proceeded with the project along those lines. Not in “wilful defiance of Parliament” but certainly taking advantage of his situation to build a quality canal. Whether you agree with this or not depends partly on your point of view.

From a Canadian point of view, Colonel By clearly did the right thing. From its conception as a tool for the military defence of Canada, to its aid in the development of Eastern Ontario, to its use today as a recreational waterway, decisions that Colonel By made, such as the larger locks and the use of a slackwater system, were and are of very great benefit to Canada.

From a British point of view, you can look at what Colonel By did in several ways. From a post-1830 Reform Government view of “don’t waste money on the colonies” – it appeared to be a big waste of money. However, when we look at the original reason for the Rideau Canal, its deterrence role in the military defence of Canada (which Britain was still responsible for), Colonel By did the absolutely correct and responsible thing in building a steamboat canal. Even though the War of 1812 was over, the United States and Britain were still vying for control of North America and tensions remained high. Locally, that culminated in the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837/38 which did involve Americans invading Canada (unsuccessfully).

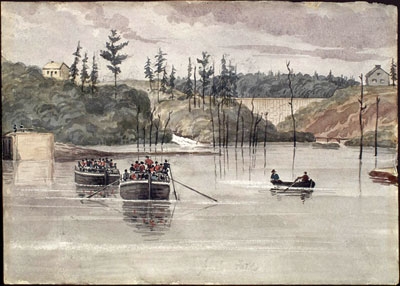

|

Military Transport in 1838

It has been said that the Rideau never served its intended role as a military transport route. That’s technically incorrect – in fact it did. This 1838 painting shows a company of Royal Marines passing through Jones Falls on June 28, 1838, on their way to Kingston. These soldiers took part a few months later in the “Battle of the Windmill” (near Prescott) against American invasion forces. One of these marines was killed and several were injured during the battle. Jones Falls, Rideau Canal, Upper Canada by Philip John Bainbrigge, 1838, Library and Archives Canada, C-011835. |

So, while not every decision that Colonel By made was a good one, on the whole, especially considering the myriad of difficulties he faced, he did a remarkable job and deserves to be recognized for the magnificent achievement of the Rideau Canal.

Sources:

The best sequential detailing of the “money story” (costs of the Rideau Canal) can be found in Robert Passfield’s “Building the Rideau Canal, A Pictorial History” (or much more extensively in his “Engineering the Defence of the Canadas; Lt. Col. John By and the Rideau Canal”). For information about John By himself, Mark Andrews’ “For King and Country, Lieutenant Colonel John By, R.E., Indefatigable Civil-Military Engineer” is a detailed biography of John By. Robert Legget also provides much information about John By, both in his book “Rideau Waterway,” and in his Historical Society of Ottawa publication, “John By; Builder of the Rideau Canal, Founder of Ottawa.”

Andrews, Mark, For King and Country, Lieutenant Colonel John By, R.E., Indefatigable Civil-Military Engineer, Heritage Merrickville Foundation, Merrickville, 1998.

Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online - John By. www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=37404.

Dictionary of National Biography, Supplement Vol. 1. edited by Sidney Lee; publ. London: Smith, Elder & Co., (1901), pages 363-364. [from: www.todayinsci.com/B/By_John/ByJohn-Bio.htm].

Hind, Edith J., Troubles of a Canal-Builder: Lieut-Col. John By and the Burgess Accusations, in “Ontario History” (Journal of the Ontario Historical Society), Vol. LVII, No. 3, pp.141-147, September, 1965.

Legget, Robert, Rideau Waterway, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1955. Second Edition 1986.

Legget, Robert, John By; Builder of the Rideau Canal, Founder of Ottawa, Historical Society of Ottawa, Ottawa, 1982.

Legget, Robert, Ottawa River Canals and the Defence of British North America, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1988.

Lockwood, Glenn J, Smiths Falls, A Social History of the Men and Women in a Rideau Canal Community, 1794-1994, Town of Smiths Falls, Smiths Falls, 1994.

Moon, Robert (Editor), Colonel By’s Friends Stood Up, Crocus House, Ottawa, 1979.

Parliament (British) House of Commons, Accounts and Papers, Session 26 October 1830 - 22 April 1831, Vol. IX.

Parliament (British) House of Commons, Report from the Select Committee Appointed to Take Into Consideration the Accounts and Papers relating to the Rideau Canal, 22 April 1831.

Passfield, Robert W., Engineering the Defence of the Canadas; Lt. Col. John By and the Rideau Canal, Manuscript Report 425, Parks Canada, Ottawa, 1980.

Passfield, Robert W., Building the Rideau Canal: A Pictorial History, Fitzhenry & Whiteside, Don Mills, 1982.

Treasury (British), Copy of Letter from the Secretary of the Ordnance, transmitting Documents respecting the Expenditures upon the Works of the Rideau Canal in Canada; together with a Copy of the Treasury Minute thereon, House of Commons, London, June 1, 1832

By’s Accolades

While we recognize today that the building of the Rideau Canal was a feat of collective human effort, from the pick and shovel labourer to Colonel By, we also recognize that Colonel By was not just a figurehead. He was directly involved in the project, from its engineering design to the huge job of project management. He was a hands-on manager, travelling the entire length of the Rideau many times each year, viewing all the work sites. He was the lead engineer and project designer – it was his lock and dam designs that were used.

He also handled all the ancillary items related to the canal, such as the many lawsuits related to land acquisition. He had to deal with several personnel issues (such as Henry Howard Burgess - see pg. 81). He had to deal with the whole organization of this mammoth project, from the creation and management of contracts to the organization of people and supplies. And, as detailed above, he had to deal with expense management and cost estimates. While doing all this, he got sick several times, likely from malaria and possibly from other diseases of the day (he was bled twice as a “cure” for the fever).

It was By’s vision, intelligence, leadership, drive and hands-on work that took the Rideau Canal project to its successful conclusion. So he fully deserves to be singled out.

The accolades to Colonel By really didn’t start to appear until the 20th century. In fact, in 1855, an accolade of sorts, the name of the community he founded, Bytown, was changed to Ottawa. Even his house, which might have stood as a remembrance, burned down in 1848. That house sat on what used to be called Colonel’s Hill, but when a park was established many years later, it took the name Major’s Hill Park, after Major Daniel Bolton who lived in the house from 1832 to 1843.

But in the 20th century, public recognition of Colonel By finally started to happen.

|

| First Tribute to ByBlocks from the old Sappers Bridge with a plaque to By in Majors Hill Park. Photo by unknown, c.1920s, Canada Dept. of Interior / Library and Archives Canada / PA-034228 |

- When the Sappers Bridge was torn down in 1912, some of the blocks were saved. In 1915, two of these, with a plaque, formed a small tribute to By near the foundations of his burned down home in Majors Hill Park (unveiled on May 27, 1915).

- In 1925, the Rideau Canal was designated a National Historic Site of Canada (plaqued in 1926 and again in 1964). Although not a direct tribute to By, this recognized the Rideau Canal’s great role in the history of Canada.

- In 1926, a small granite base for a proposed statue of By was unveiled, however the statue was never built.

- In 1954, Lieutenant-Colonel John By was designated a person of “National Historic Significance” by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. This designation has never been plaqued, and the HSMBC currently notes “No plaquing planned”.

- In 1954, the old road from Hogs Back to Dows Lake was named “Colonel By Drive” (in a ceremony with the Queen Mother). Since that time, several buildings in the Ottawa area have taken on the name “Colonel By.”

- In 1955, a fountain memorial to Lt.-Colonel By was unveiled in Ottawa. It 1975 it was moved to Confederation Park.

- In 1971, a beautiful statue of Lt. Col. By, created by sculpture Emile Brunet, was unveiled in Majors Hill Park

- In 1971, the name “Colonel By Lake” (the lake above Kingston Mills) appeared on maps in an area formerly known simply as “drowned lands”

- In 1979 a commemorative stamp of Lt.-Colonel By was issued to celebrate the bicentenary of his birth.

- The Ontario Heritage Foundation erected a plaque to John By at Jones Falls. They also placed a plaque to John By at Lambeth Town Hall, Borough of Lambeth (By’s birthplace), London, England.

- In Big Rideau Lake, the island formerly known as Livingston Island was renamed “Colonel By Island.” It’s owned by Parks Canada.

- Entrance Valley in Ottawa (site of the Ottawa Locks) was renamed Colonel By Valley.

- In Ottawa, the Ontario Civic Holiday (first Monday in August) is known as “Colonel By Day”

- Archaeological work was done on the remains of Colonel By’s house in Majors Hill Park and an interpretive display erected near the foundations of this house.

- In 2007, the Rideau Canal was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. One of the UNESCO criteria chosen for the Rideau was that it represented a masterpiece of human creative genius. Much of that genius is due to Lt.-Colonel John By – we have him to thank for today’s international recognition of the Rideau Canal.

|

| Statue of Colonel By in Majors Hill Park, Ottawa. Photo by: Ken W. Watson |

The Henry Howard Burgess Affair

An issue that helped to cloud Colonel By’s reputation was the Henry Howard Burgess affair. Burgess was a young man hired as a clerk in the Engineering Office of the Rideau Canal in 1826. He was hired based on references from his godfather, Colonel Howard of the 23rd Lancers and also from the Anglican Bishop of Québec. He seems to have been a good and diligent worker up until about November of 1829. At that time he asked for a letter of recommendation, which Colonel By quickly provided. His work habits deteriorated from that point on, he became prone to public drunkenness and violent outbursts. He submitted a letter of resignation to Colonel By on January 2, 1830, which Colonel By did not accept. Burgess’ erratic behaviour intensified, By’s staff reported many incidents of insubordination and missed duty. His behaviour caused Burgess to be thrown out of several lodging houses in Bytown. On March 31, 1830, Colonel By dismissed Burgess on the basis of “neglect of duty.”

Burgess protested his dismissal and demanded that he be paid up to the end of his contract period, August 1831. His demand was turned down and nothing more was heard of Burgess until November 1830. He again demanded payment, but this time added the threat that he would inform Colonel By’s superiors that Colonel By was misusing public funds. Payment was again refused and so in April 1831 he made good on his threat, writing to the Board of Ordnance, accusing Colonel By of inappropriate use of public funds.

He lobbied the Board of Ordnance to go to London to present his case. He finally got that trip in early summer 1831. He managed to convince a member of Parliament, William Ewart, to take up his case, and Ewart pressed the Board of Ordnance to take action. Burgess also got his charges aired in public; the Liverpool Chronicle published all of Burgess’ allegations in September 1831. The mood of the people in England was not in favour of spending their tax dollars in the colonies on large projects such as the Rideau Canal. This put pressure on Ordnance to do something about Burgess’ charges.

The Board of Ordnance took action, convening a Court of Inquiry in Bytown, under Colonel Gustavus Nicolls, R.E., in November 1831. The first part of the session examined Burgess’ claim for more pay. They found his claims to be unwarranted, he had been paid up until his dismissal. The second part was in regard to Burgess’ claim of accounting irregularities. They examined copies of vouchers for work between the Ottawa Locks and the Hogs Back Locks, which Burgess had provided to prove his case. On detailed examination, the court concluded that the accounting was proper, that it was Burgess who didn’t understand the accounting system. On another charge, that of using civil and military tradesmen to do private work, and of those tradesmen being paid by the Crown, it was found that although this was common practice, in all cases the amount of that work was deducted from the pay of those officers. In addition, the court also found that Colonel By had personally paid for his house, government funds had not been used.

The first court was held before Burgess got back to Bytown, so the court re-convened on January 20, 1832, to allow Burgess to make his case in person. But after only one day before the court, Burgess refused to have anything more to do with it. The court continued to examine the “evidence” and adjourned on February 27, 1832.

In the end, Colonel By was fully exonerated by the Court of Inquiry. One of their recommendations was that the Board of Ordnance should essentially ignore any further charges brought by Burgess. It was good advice since Burgess continued to write to the Board, with various threats, charges and innuendo, up until 1849. A Board of Ordnance memo attached to Burgess’ final December 14, 1849, letter stated that Burgess was “labouring under a mental delusion.”

Although Colonel By was cleared of all the charges, the fact that these were brought up in the first place, and made public, contributed to the public “taint” that Colonel By acquired and, together with the Parliamentary inquiry, contributed to the lack of any honours bestowed on Colonel By when he returned to England.

The following is the text from the actual treasury minute of May 25, 1832. It was never officially communicated to By, he was to first see this in the papers after he returned to England.

TREASURY MINUTE

25 May 1832

MY LORDS have under their serious consideration the Letter from the Secretary of the Ordnance of the 21st instant, transmitting to this Board a Letter from Colonel By, of 27th February 1832, accompanied by various explanatory Documents and Accounts, upon the subject of the Expenditure on the Works at the Rideau Canal to the close of 1831, and of that required to complete the Canal, the opening of which was expected to take place in the course of the present month.

My Lords will take into their future consideration these voluminous Accounts and Papers; but they cannot delay expressing their opinion to the Master General and Board of Ordnance on the conduct of Colonel By in carrying on this Work.

It appears from that Officer's Letter, and from the Report of the Inspector General of Fortifications thereon, that Colonel By had actually expended to the close of the year 1831, £.715,408. 15. 6., being £.22,742. 15. 6. more than had been granted for this Work by Parliament; and that without waiting for any authority from this country, he has gone on during the present year with a further Expenditure, entirely unsanctioned, and which it is stated will probably amount to £. 60,615. 10., making an excess of £.83,358. 5. 6. beyond the amount, granted by Parliament. The Expenditure which was contemplated for this Canal, when the subject was immediately under the consideration of the Select Committee of the House of Commons in 1831, and the whole Expenditure for which any order has at any time been given by any competent authority, is £.693,448., exclusive of £.69,230. for Blockhouses and Works of Defence not sanctioned. In order therefore to complete the Work, Colonel By has, upon his own responsibility, thought proper to expend no less than £.82,576. My Lords assuming from these Papers that the Work has actually been carried on to its completion, since the date of Colonel By's Letter of February last, and that the expense has not been less than the sum at which he then calculated it.

It is impossible for My Lords to permit such conduct to be pursued by any public functionary. If My Lords were to allow any person whatever to expend with impunity, and particularly after repeated increases of the original Estimate, upon any work under his superintendance, a larger amount than that sanctioned by Parliament and by this Board, there would be an end of all control, and My Lords would feel themselves deeply responsible to Parliament. They desire, therefore, that the Master General and Board will take immediate steps for removing Colonel By from any further superintendance over any part of the Works for making Canal Communication in Canada, and for placing some competent, person in charge of those Works, upon whose knowledge and discretion due reliance can be placed ; to whom must be furnished a Statement of the Estimates and Grants, and who must be strictly charged upon no account whatever to exceed the amount of the Grants.

My Lords further desire that Colonel By may be forthwith ordered to return to this country, that he may be called upon to afford such explanation as My Lords may consider necessary upon this important subject.

Let Copies of these Papers and of this Minute be forthwith prepared, with a view to their being laid before The House of Commons.

Lt. Col. By's February 23, 1832 Estimates

Part of the Treasury Minute included By's 25 item, 11 column detailed estimate of February 23, 1832. Of interest is By’s lock by lock breakdown. Although not the final cost, it’s close enough to provide a lock by lock comparison of the cost of building the Rideau Canal (most of the extra costs to reach the final £822,804 figure were land acquisition/compensation costs). Comparison to today's dollars is difficult. It would cost well over 500 million dollars to build the Rideau today, so that would require a multiplication factor of at least 600 to the numbers below.

Spelling has been left as in the original document. Figures have been rounded.

| Location |

Amount

Expended

+ Estimate

(pounds) |

| Entrance Valley & first 8 Locks |

70,448 |

| From Eight Locks to Hogs Back [includes Hartwells] |

63,612 |

| Hogs Back |

35,472 |

| Black Rapids |

14,170 |

| Long Island |

44,292 |

| Burrets [sic] Rapids |

14,004 |

| Nicholson's Rapids |

16,414 |

| Clowe's Quarry |

12,016 |

| Merrick's Mills |

22,362 |

| Maitland's Rapids [Kilmarnock] |

12,394 |

| Edmond's Rapids & Phillip's Bay |

11,263 |

| Old Sly's Rapids |

20,409 |

| Smith's Falls |

28,856 |

| First Rapids [Poonamalie] |

26,633 |

| Oliver's Ferry |

-- |

| Narrow's Rideau Lake |

7,563 |

| Isthmus [Newboro] |

31,578 |

| Chaffy's Mills & Small Isthmus, Indian Lake |

12,880 |

| Davies' Rapids |

8,834 |

| Jones' Falls, Cranberry Marsh & White Fish |

80,357 |

| Brewer's Upper Mill & Round Tail |

20,841 |

| Brewer's Lower Mill |

10,843 |

| Kingston Mills, Jacks & Billidore Rifts & Cataroque |

60,292 |

| Civil & Military Establishment. Barracks & General Contingencies |

110,279 |

| Locks, Gates, Cills, &c. |

23,141 |

| Purchase of Land & Compensation for Damages |

44,807 |

| TOTAL |

803,774 |

|