A Grave Revealing

by Ken W. Watson

By the mid-20th century, the hardships of building the Rideau Canal, including the locations of many of the original “burying grounds” along the canal, were long forgotten. At Jones Falls, a new gravel pit was in the process of being opened up. The crews had been working in the pit for a few days, and were now making their way towards a small knoll. The front end loader was finding it easy digging in the loosely consolidated gravel, an ideal location for a gravel pit. Over a hundred years before, this same loose gravel had been the ideal location for a cemetery. The work crew, concentrating on the job of loading trucks with gravel, were completely unaware of this bit of local history.

As the loader dug into the bank of the knoll, Joe, one of the workers, saw something that didn’t look quite right. He motioned the loader operator to stop and approached the exposed side of the bank. He stared at it, trying to figure out what exactly he was looking at. It took him a few seconds to realize that it was a skull, starting right back at him.

The loader operator later stated, “Yup, Joe must have jumped three feet straight up. Then all I could see was frantic arm-waving as he skedaddled out of there, yelling at me to back off. So that’s what I did.” When the loader backed up, the side of the hill collapsed and a skeleton, dressed in a blue uniform, tumbled from the grave it had been resting in.

“Get the police!” cried Joe and one of the men ran off, jumping into his truck and racing into Elgin to get help.

By the time he returned with the authorities, the men at the site had come to realize that this was not a recent burial. In addition, while poking around, they found that they had uncovered the skeletons of at least three bodies. It didn’t take long for the local grapevine to go into high gear and soon all sorts of people were showing up.

It was an old timer who solved the mystery. “This must be the old burying ground” he said. “I remember being told, when I was just a young lad, that when the Rideau Canal was being built, there was a burying ground near the Great Dam. This must be it.”

Exposed to sun and air, the blue uniform was starting to disintegrate. All that could be saved were the brass buttons. One of the local men, Robert McGuire, gathered up the remains of the skeletons, put them in a box and re-buried them on the site. Needless to say, the gravel pit was shut down.

It was initially thought that the uniform belonged to a soldier stationed at Jones Falls during the construction of the Rideau Canal, however the brass buttons dated to the mid-1800s. The skeleton belonged to someone who had died and been buried many years after the building of the canal. The exact identity of the man was never determined.

|

| Jones Falls CemeteryThe only clue today that this was a cemetery are some of the field stones that were used as grave markers. The original wooden markers on these graves have long since rotted away. Photo by: Ken W. Watson, 2003 |

Although the cemetery was originally started to inter the men who died during the construction of the locks and dam at Jones Falls, this cemetery, like many other canal cemeteries, saw continued use until the mid 1800s. Lockmaster Peter Sweeney, in the June 26, 1846, entry in his diary, stated that “Mrs. Sergant’s child buried at the burying ground.” It was this cemetery that Sweeney was referring to.

By the late 1800s, most of these local and family cemeteries had fallen out of use, in favour of the more formalized church cemeteries. Many of these old cemeteries, such as the one at Jones Falls, were abandoned, and, over time, forgotten. That is, until the unwary gravel pit crew rediscovered the original use of this land.

Who is Buried Here?

Many myths and misconceptions have grown over the years about death and burial during the building of the Rideau Canal. A recent example of this is a series of articles in the Ottawa Citizen, which, referencing the Sappers and Miners who died at Newboro, stated that “even the Royal Sappers, whom he [Colonel By] dispatched to the summit, died in such numbers they were buried in unmarked graves beside the labourers.” What would be your guess at a number based on that statement? Dozens? Hundreds? The total number of Sappers and Miners who died during the entire construction of the Rideau Canal was 22. If we assume that about half of them died at Newboro, then “died in such numbers” equals 11. The reporter obviously didn't do much fact checking.

|

| Margaret Davidson HeadstoneMargaret Davidson died at 2 years of age in 1829. She was the daughter of P. Davidson, a canal contractor (likely at Clowes). This headstone is located in the McGuigan Cemetery. For a larger photo, click here. Photo by: Ken W. Watson, 2007 |

Were the graves unmarked? No – the graves were marked with wooden markers which have long since rotted away. Headstones, even for locals, were rare at the time, although some do exist. What does remain in these old cemeteries are some of the fieldstones that were used in conjunction with the wooden markers.

In assessing how many were buried in these old cemeteries, we are faced with the problem that there are no firm numbers for how many died during the building of the Rideau Canal. And, even if we could count the graves in these cemeteries, the numbers would be meaningless in terms of canal era deaths, since many of these cemeteries saw continued use for upwards of 50 years after the building of the Rideau Canal. There is no way to distinguish an 1830 grave from an 1840 grave (unless you can find some brass buttons).

Today’s tendency to “pump the numbers,” such as our reporter did with the exaggeration of the deaths at Newboro, is not a new phenomenon. In a book written in 1833, a traveller who visited the Rideau (likely in 1829), stated “Then comes the dreadful swamp called Cranberry Marsh, 18 miles long and two broad, where some thousand stout labourers have met their death of regular yellow fever.” Should we take that statement as factual truth? No – outside of the fact that there was no yellow fever on the Rideau, the number is simply a large made-up rounded number indicating lots of deaths. By the 20th century that particular number had grown: the August 4, 1948 edition of the Ottawa Citizen reported that “Cranberry Marsh extracted a toll of many thousands of lives.”

Today we use the round number of 1,000 as an estimate of the total number of men and family members who died during the construction of the Rideau Canal. This 1,000 number is just a very rough guess. The single largest cause of death was malaria (and the complications from it in combination with other diseases and health issues of the day, see “Malaria: The Secret Immigrant”). The best estimate for deaths from this is about 400 to 600 people. Many others died from other diseases of the day.

Then there were the accidents. For instance, we know that during the construction period, 5 Sappers and Miners died from blasting related accidents and one died by drowning (the remaining 16 died of sickness or had no cause given). However, there were few reports of accidents in the papers of the day. In fact, the Montreal Herald reported in its December 15, 1827 edition “The last advices from the Rideau Canal, we regret to state, mention the occurrence of a number of distressing accidents. Two labourers have been smothered by a bank of clay falling on them at Hog’s Back. … Considering, however, the extent of the works, and the dangerous nature of many of them, there have been fewer accidents since the commencement, than could have been supposed. Two have been before this killed by blasts … and one killed by a tree falling on him.”

We also know that women and children died from disease at the canal construction sites. Deaths from malaria were in almost equal number to the men. For instance, in 1830, 27 (of 1,327) men were recorded as having died of malaria at the southern lockstations (Kingston Mills to Newboro). Those same records show that 28 women and children also died.

Alexander J. Christie (hired by Colonel By to look after the medical needs of the workers in 1827) reported that, between May and December 1827, 10 men died of disease (this was before malaria struck in 1828) and 7 from accidents. In that same time period, 6 women and 38 children also died. He treated 1,278 men for various ailments, mostly stomach and/or bowel issues. On a more positive note, he recorded 54 births that year along the canal.

|

| Canal Era CemeteriesFrom top to bottom: Chaffey's cemetery, McGuigan Cemetery and Newboro cemetery. These cemeteries are open to the public. Photos by: Ken W. Watson |

Those who died were all buried in cemeteries located relatively close to the works. There may have been upwards of twenty cemeteries in use during the canal construction period. Three of these have been restored and are open to the public; the cemetery at Chaffeys Lock, the Old Presbyterian Cemetery at Newboro, and McGuigan Cemetery near Merrickville. Other cemeteries have been lost forever to urban sprawl, such as the old Ward Burial Ground in Smiths Falls and the old Barrack Hill Burial Ground in Ottawa. Still others, such as the long abandoned “burying grounds” at Jones Falls, Upper Brewers and Lower Brewers, are presently located on private land.

Who and how many were buried at Jones Falls? During canal construction, the crews at Jones Falls were comprised mainly of Scots and French-Canadians working for contractor John Redpath. We know that in 1828, during the first outbreak of malaria, of 246 men at Jones Falls, 146 were recorded as taking sick and 2 died. No women or children are recorded as dying in that year. In 1830, we know that at least 55 men, women and children died between Kingston Mills and Newboro, presumably including some at Jones Falls.

So, for the canal construction period, we might account for a few dozen burials at Jones Falls. However, the cemetery saw continued use after the canal was opened. This wouldn’t have been just for locals, there were also deaths among the thousands of immigrants who passed through the Rideau Canal in the 1830s, 40s and 50s. Any who died on the trip would have been buried in a local cemetery, such as the one at Jones Falls. Diseases such as cholera and typhoid were prevalent in the various waves of immigration and immigrants did die en-route. Kingston banned the arrival of boats with dead on board, further necessitating the use of local Rideau cemeteries. So, in the post-canal era, several dozen, perhaps more than from the canal construction era itself, would have been buried here.

With the establishment of formal church and civil cemeteries, these local “burying grounds” stopped being used. Over time they became overgrown, the memory of their very existence eventually forgotten. The digging of a gravel pit into a long forgotten, abandoned cemetery is one of the more extreme examples of being lost to time.

We have no reliable detailed accounts of death, sickness and burial during the building of the Rideau Canal. A cautionary tale in accepting local anecdotal history as the truth is seen with storyteller, G. Clare Churchill. He records that the sick from Jones Falls were taken to a temporary “hospital,” a log cabin located on Sand Lake Road near Bush Road, and that several of the local women looked after the sick men. Churchill states that one of the ladies, a Mrs. Baker, died of malaria. He also notes that a Mrs. John Gilpin was responsible for preparing the bodies for burial.

That story is correct in as much as Sand Lake Road was part of the road used to transport the stones from the quarry to Jones Falls and so it did exist in the canal construction period. But local historian Sue Warren points out several discrepancies with Churchill’s story, including the facts that the log cabin he refers to wasn’t built until the 1840s, and that Mrs. Baker was alive and kicking at the time of canal construction (she passed away in the late 1840s). Churchill’s tale is referring to a later, post-canal epidemic, and, similar to many other local “histories” and anecdotal tales, got the time periods mixed up.

So, what do we really know about how people lived and died during the building of the Rideau Canal?

Life and Death during the Construction of the Rideau Canal

From 2,000 to 3,000 men worked portions of each year building the Rideau Canal. They comprised various groups: there were the Royal Sappers and Miners (162 men from the British Isles); the contractors (mostly from Canada, some U.S.); the various skilled tradesmen (carpenters, masons, smiths, coopers, etc.), comprised mostly of men from the British Isles and from Upper (Ontario) and Lower (Québec) Canada; and the labourers, who were about 60% immigrant Irish and 40% French-Canadian.

|

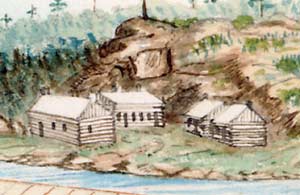

The Lock Construction Camp at Jones Falls

Located at the spot now occupied by the Blacksmith’s shop at Jones Falls, these buildings didn’t prevent malaria carrying mosquitoes from entering at night. Section from “Basin and upper lock at Jones' Falls, from the East Upper end of 3rd lock, works nearly completed” by Thomas Burrowes, October 1831, Archives of Ontario, C 1-0-0-0-55.

|

|

Log Houses at Long Island

Workers with families built log cabins for themselves at the work sites. “Settlement on Long Island on the Rideau River, Upper Canada.” by James Pattison Cockburn, August 17, 1830, Library and Archives Canada, C-040048.

|

They lived in construction camps which generally consisted of log buildings. The diet would have been rather monotonous; pork and bread were the main staples. Rum and whiskey also show up with regularity in the records. The British Ordnance department provided some of the contractors with supplies at cost. For instance in March 1827, some 2,774 lbs of flour, 6,600 lbs of salt pork and 47 barrels of rum were shipped to the department for distribution to the contractors.

Local farmers also took advantage of the project, with produce and meat from as far away as Brockville and Prescott shipped to Rideau construction camps. Workers with families on site built their own cabins and many grew their own staples such as potatoes. The records for Philemon Wright show that shipments to his construction camps included flour, biscuits, potatoes, oats, fish, pork, bread, corn, bran, pease [sic], and grain.

Living quarters at the work sites were most commonly log cabins. Some of the construction sites became small villages. For instance, at Kingston Mills, a census done in November 1830 showed 101 buildings located on the site, including three licensed public houses (O’Reilly’s, Franklin’s, and Mahoney’s), a Catholic chapel, a store, and a schoolhouse.

Most of the work sites, such as Jones Falls, were well managed, but disease remained a big problem. Poorly understood, illness cut across all social classes. Malaria was the biggest problem and it didn’t discriminate. From the lowliest labourer to Colonel By, many contracted the disease. But there were other problems, and the apparent mortality rate from malaria is likely a result of complications from malaria and other ailments of the day.

These ailments included consumption (tuberculosis), dysentery, gonorrhea, syphilis, hepatitis, opthalmia (pink eye), and phlegm (one of the four “humours” – associated with sluggishness or apathy). Bowel and stomach disorders such as constipation, diarrhea, and indigestion were common. Although “fever” is generally attributed to malaria, there were other fevers present, some from virus, some from infection. But in the southern Rideau, it was a temperate form of malaria, complicated by other ailments, that appears to have been the main killer. The “plague” illnesses of the era, such as cholera and typhoid, were to come later, after the completion of the canal. Only a few cases of cholera were recorded by the doctors during construction. The first major outbreak of that killer disease came in June 1832, after the canal was completed (that outbreak originated in Québec City).

Another problem was alcoholism; there may well have been deaths from alcohol poisoning and cirrhosis of the liver, given the amount of alcohol that was consumed on some of the sites. At Burritts Rapids for instance, several of the workmen were drinking over a gallon of whiskey a week. At Jones Falls, the workers had a choice of rum, whiskey, brandy or beer. John Mactaggart warned about the dangers of locally distilled potato whiskey – “the laudanum that sends thousands of settlers to their eternal rest every season” – an exaggeration to be sure, yet indicative of a problem.

Alcohol was a contributing factor in some accidents. The jury at the inquest into the death of John Rusenstrom, killed in a fall from the Hogs Back dam, found that his death was the “consequence of intoxication by Ardent Spirits.” Another incident involved Patrick Sweeney, a construction labourer at Old Slys. He drowned while trying to swim across the Rideau River to obtain another bottle of whiskey. He was inebriated when he made the attempt. In the August 1831 inquest into his death, the coroner stated: “When last seen alive, he was going down with a bottle or flask in his mouth.” But the story doesn’t end there. His grave was dug by William Ferguson, a fellow labourer. Ferguson, “after returning from the funeral, expired in the open streets at Smiths’ Falls, in the arms of his fellow workmen.” The jury in the inquest into his death concluded that it “was caused by intemperance.”

Tobacco use was also very common and likely didn’t help anyone with lung issues such as tuberculosis.

On top of all of this were issues with the medical care of the day. Firstly, little medical care was available, with only a few doctors looking after the needs of the workers. And secondly, the medical “care” at the time was somewhat problematic, in many cases hindering rather than helping the patient’s health. Bleeding and purgatives were commonly used by doctors to “cleanse the system.” Colonel By himself was bled twice as a “cure” for fever.

Although, compared to today, death was an all too common occurrence back in that era, not only in the construction camps, but in the villages, towns and cities, it was not taken lightly. When a death by accident occurred at a Rideau construction site, an inquest into that death was held. That was the law.

A funeral, giving proper respect to the deceased, was also held. We have the previous mention of the funeral of Patrick Sweeney (presumably followed by the funeral of William Ferguson). Another is described by Captain J.E. Alexander during a visit to Kingston Mills in 1829. “Whilst viewing the extensive works at the entrance valley, enclosed with lofty granite cliffs, covered with birch and pine, a funeral passed us, consisting of several light two-wheeled waggons, each drawn by a span of horses. Women and men sat in three rows in these primitive conveyances, and the coffin, covered with a white sheet, lay among the straw of the leading one.”

Coming back to the cemetery at Jones Falls – the majority of canal workers interred here would likely have died of disease, mostly from complications of the previously listed variety of health issues. Malaria hit hard at this location. John Redpath, the contractor at Jones Falls, in a letter written from Jones Falls in December 1831, said “the exceeding unhealthiness of the place from which cause all engaged in it suffered much from lake fever and fever & ague, and it has also retarded the work for about three months each year. I caught the disease both the first [1828] and second year missed the third but this year had a severe attack of Lake Fever – which kept me to bed for two months and nearly two months more before I was fit for active service as nothing can compensate for the worse of health so no inducement whatever would stimulate one to a similar undertaking.”

Ironically, in 1834, Redpath brought his family to his sister’s house at Jones Falls, to escape the deadly cholera epidemic (which had killed his wife), that was raging at that time in Montreal.

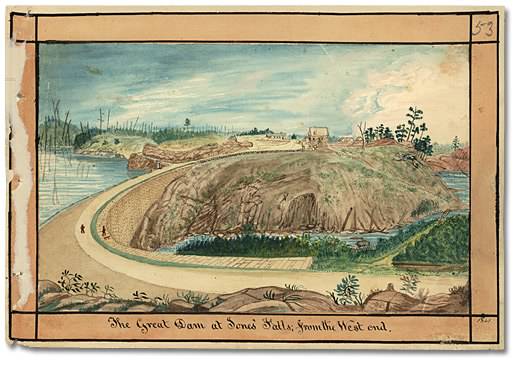

|

Jones Falls 1841

During the building of the locks and dam, the houses shown in this image, on the top of the hill, were part of the construction camp for the dam. It was known at the time as "Esthertown" (after Colonel By's wife Esther). After completion of the dam, these buildings became the nucleus for the small community of Jones Falls. “The Great dam at Jones’ Falls; from the West end, 1841” by Thomas Burrowes, 1841, Archives of Ontario, C 1-0-0-0-53.

|

The cemetery saw continued use over the years. This wouldn't only have been for locals, there were deaths among the thousands of immigrants that passed through the Rideau Canal in the 1830s, 40s and 50s. Any dying on the trip would have been buried in a local cemetery, such as the one at Jones Falls. Diseases such as cholera and typhoid were prevalent in the various waves of immigration and immigrants did die en-route. Some places such as Kingston banned the arrival of boats with dead on board, further necessitating the use of local Rideau cemeteries. So, in the post-canal era, several more dozens, perhaps more than from the canal construction era itself, would have been buried here.

The numbers though aren’t really the story. The number of deaths was typical of such projects of the day, and the Rideau was not out of the ordinary in this regard. These old cemeteries provide a tangible link to the incredible human effort and sacrifice that went into the building of the Rideau Canal.

Public Canal Era Cemeteries

The following three cemeteries, which contain canal era burials, are open to the general public. All three span a much greater time period that just the canal construction years, and therefore also contain many non-canal related burials. The first burial in Chaffey’s Cemetery was in about 1825 and the cemetery saw regular use to the late 1800s. The last burials in that cemetery took place in 1930. The Old Presbyterian Cemetery started during the canal construction period and remained in use to the 1940s. That cemetery also contains the graves of the Royal Sappers and Miners who died at Newboro. Burials in McGuigan Cemetery span almost a hundred years, from the early 1800s to the late 1890s.

Chaffey’s Cemetery (and Memory Wall) is located beside Brown’s Marina in Chaffeys Lock (44° 34.890’ N - 76° 19.020’ W).

The Old Presbyterian Cemetery is located just outside of Newboro, on County Road 42, on the west side of the Rideau Canal, on the north side of the road (44° 38.940’ N - 76° 19.625’ W).

McGuigan Cemetery is located at 448 Country Rd. 23, directly across the river from Clowes Lock, about 0.8 km south on River Road from Upper Nicholsons Lockstation. From Merrickville, follow Cty Rd. 43 east towards Kemptville and take the first turn off for Burritts Rapids, this is Cty. Rd. 23 (44° 56.680’ N - 76° 49.238’ W).

For more information and pictures about the various cemeteries and memorials on the Rideau, see my Memorials and Markers Page.

For more information on malaria, see: Malaria Mythconceptions and Malaria on the Rideau

Sources:

Bush, Edward F., The Builders of the Rideau Canal, 1826-32, Manuscript Report 185, Parks Canada, Ottawa, 1976.

Churchill, G. Clare, Rideau Reflections, 1000 Island Publisher, abt. 1992.

Corbett, Ron, “A River Created: The Story of the Rideau Canal, Part IV”, Ottawa Citizen, August 5, 2006.

MacTaggart, John, Three Years In Canada, two volumes, London, 1829.

Lockwood, Glenn J,

Smiths Falls, A Social History of the Men and Women in a Rideau Canal

Community, 1794-1994, Town of Smiths Falls, Smiths Falls, 1994.

McCord Museum, Montreal - Redpath papers, P085 and Garneau Papers, 20145-20175.

Moon, Robert (Editor), Colonel By’s Friends Stood Up, Crocus House, Ottawa, 1979

Patterson, William J., Lilacs and Limestone, An Illustrated History of Pittsburgh Township, 1787-1987, Pittsburgh Historical Society, 1989

Price, Karen, "Construction History of the Rideau Canal," Manuscript Report 193, Parks Canada, Ottawa, 1976.

Stanzell, John “Royal Sappers and Miners: Builders of the Rideau Canal 1826-1831” Ontario Genealogical Society, Ottawa Branch News, V.40, No.4, pp 199-200, August-October 2007

Valentine, Jaime, Supplying the Rideau: Workers, Provisions and Health Care During the Construction of the Rideau Canal, 1826-1832, Microfiche Report Series 249, Parks Canada, 1985

Warren, Sue, per comm, 2008

|