The Sluiced Superintendent

by Ken W. Watson

It was a hot day in July 1899. Long Island Lockmaster George Clark could feel the sweat dripping down his back as he waited for the Superintending Engineer of the Rideau Canal to arrive. Clark wanted to blame the sweat on the heat, but he was also quite nervous. He had a bone to pick with the Superintendent.

Clark had sent various missives into the Superintendent’s office regarding the lack of maintenance funding, but the dollars for needed repairs weren’t forthcoming. Now he had a chance to talk to the Superintendent face to face. But how to approach the subject? Perhaps if he were to point out an example of a maintenance problem. Perhaps one that was a potential danger to the public. Yes, that was it, a public danger. Now, what would be a good example?

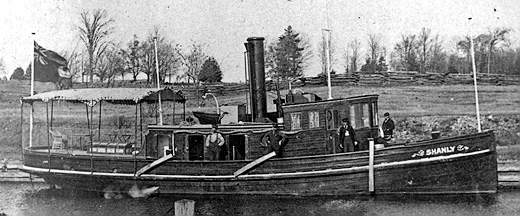

As Clark pondered that question, he heard a steam whistle blow. The Superintendent was arriving! Clark could see the tug Shanly, with Captain Nevins at the helm, heading towards the lower lock. He checked to see that all his men were at their stations and did a last visual check of the lockstation. Superintendent Phillips didn’t tolerate slovenliness, either with his men, or in the appearance of the lockstations. Clark was glad to see that his men were all in proper position, ready to lock the Shanly through. He hastened to greet the Superintendent who was now stepping onto the wharf.

|

| Steam Tug "Shanly"The Superintendent's "comfy chair" sits on the rear deck of the tug Shanly, owned by the Department of Railways and Canals, and used as a patrol boat. It operated from 1890 to 1907. When the Superintendent was on board everything had to be absolutely spotless. Photo: n.d., Parks Canada, Rideau Canal Office, No.340 |

“I’ve been reading your memos Clark and I simply don’t agree that the situation is as dire as you make it out to be. Money is tight, we have to make the best use of our limited funding, we just can’t throw it away on frivolous items.”

“But Sir,” replied Clark, “it’s a matter of public safety.”

“Come now Clark. The public is perfectly safe, we’ve got a fine maintenance system in place, our locks and dams are perfectly sound.”

“It’s not just the locks Sir,” said Clark, looking around, still searching for a good example to bolster his argument. There it was, the perfect example!

“See here Sir,” Clark said, pointing to the wooden grating covering the top of the manhole that led down to the tunnel sluice. “These are a danger to the public, they are badly in need of replacement. Someone is going to fall through and sue us.” There, the argument was made. Clark felt good about adding the “sue us” part. He had heard that Phillips vehemently hated dealing with the various lawsuits brought against the Rideau Canal.

“Nonsense man – wood is as strong as iron in the right application,” replied Phillips, walking over to the grate.

The lock staff, having closed the lower gates, were now at the top of the lock, opening up the tunnel sluices to raise the water in the lower lock. Clark could hear the rush of water going through the sluice as the Superintendent walked over to stand on the wooden grating.

“See,” said the Superintendent, “strong as iron,” and to make his point, the Superintendent jumped up and down on the grating. The partially rotted wood gave way with a loud crack and Clark watched in horror as the Superintendent disappeared from sight down the manhole.

Clark and his men rushed to the side of the lock just in time to see the Superintendent flushed into the lock by the force of water going through the sluice. Clark threw a rope to the sputtering Superintendent as one of the younger lads rushed down the ladder to help him out of the lock.

As Clark helped the shaken, but uninjured, Phillips to the lockmaster’s house to get out of his wet clothes, he heard him mutter “your point is taken Clark – you’ll get your needed repairs.”

|

| Iron Grating Covering ManholeThe iron grating, in use over the manholes since 1900. The Rideau hasn't lost a single Superintendent since that time. Photo by Ken Watson, 2007 |

This is a true (if somewhat embellished) story. The official records simply state that Superintendent Phillips was standing on the wooden grating when it gave way, dropping him into the tunnel sluice, the rushing water in the sluice shooting him out into the lock chamber. Phillips himself wrote in his journal “Long Island - Dropped through lower manhole of upper lock & came out in lower lock at 5 PM. Most miraculous escape.”

On his next (August 1899) inspection tour, he made a point of noting the condition of the manhole covers at the lockstations, finding many in poor condition. Phillips subsequently ordered that all the wooden gratings be replaced with iron gratings.

The interesting question regarding this incident is how is it possible for a man to fall ten or so feet (3 m) into the sluice and survive, apparently with no serious injury?

|

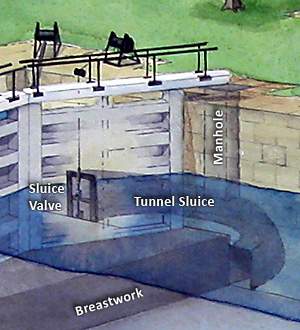

Diagram showing a typical tunnel sluice.

Diagram by Parks Canada, annotated by Ken Watson |

One of the design features of a Rideau lock is the tunnel sluice (or sluice culvert), a method of getting water from the upper navigation level into the lock without creating a huge amount of turbulence in the lock. This is done by means of a tunnel through the breastwork of the lock. The breastwork is the foundation on which the upper lock gates sit. It’s a big lump of masonry (stonework), that extends down to the base of the lock.

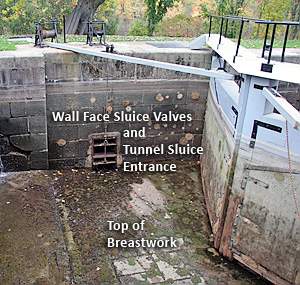

To get the water into the lock from the upper navigation level, tunnels, one on each side of the lock, were constructed through the sides of the breastwork. These are both curved and sloped, about 3 feet wide by 5 feet high. There is a rectangular entrance to the sluice at the upper level, covered by a gate valve. It is the opening of this valve that lets water into the sluice and into the lock. The bottom of the sluice is simply a rectangular opening into the lock.

|

| Tunnel Sluice EntranceThis photo, taken in the fall with the top of the lock dry, shows the on-wall valves at the entrance to the tunnel sluice. Photo by Ken Watson, 2007 |

|

Tunnel Sluice ExitThis photo, taken with the lock empty in the fall, shows the open hole of the tunnel sluice exit. The light colour at the bottom of the lock wall shows the normal depth of water in lock at the level of lower navigation. Phillips would have been flushed out of a hole similar to this one, underwater into the lock. Photo by Ken Watson, 2007

|

|

| Bottom of ManholeThis is essentially what Phillips fell into, a rush of water going through the sluice (much more water than this photo shows). Photo by Ken Watson, 2009 |

The original valves for most of the sluices were actually located inside the sluice. The square manhole allowed the lifting rods for the sluice valves to pass from the valves (in the tunnel sluice) up to the rack and pinion valve opening/closing mechanism. It also provided venting in order to prevent an air lock in the sluice and gave access to the valves for repairs. Only at Kingston Mill and Jones Falls were wall-face valves originally used, and in these locations a much smaller air vent was substituted for the larger manhole. The in-sluice valves caused many problems, and in 1839 all the locks were converted to wall-face valves, but the large manholes (which were built in solid stone) remained.

The reasons that Phillips survived relatively unscathed is due both to the design of the sluice as just an open hole with no projections or obstructions, and to the fact that it was in use at the time, at the start of the lockage cycle, so there was a cushioning rush of water. If he had fallen through when the sluice wasn’t open, he would have landed hard on bare rock, and bones would likely have been broken. Or if he had fallen through when the lower lock was at full lift, he would have fallen into standing water and possibly drowned before he could have been rescued.

Had Clark really complained about lack of maintenance funding? It’s very conceivable that he had since the Rideau, particularly in the mid-late 1800s, was woefully undercapitalized. Only dire repairs were made. Replacements, except where there was a clear public danger (i.e. the weirs) were rare. This is fortunate for us, since much of the original heritage fabric of the Rideau still exists because structures were repaired rather than replaced. Today the heritage values of the canal are factored into any engineering repair/re-construction, but back at the turn of the last century, if there had been an unlimited capital budget, all the locks would have likely been redone in concrete.

The next time you visit a Rideau lock, stand on the iron grating covering a manhole. Listen to the sound of rushing water when the lock staff open up the sluice valves and think about poor Superintendent Phillips getting flushed into the lock.

Sources:

Bebee, Edward, per. comm., 2008. Sourced from Library and Archives Canada, RG43. C1.1.(b) Reports of Official Inspections 1898-99 and 1900.

Passfield, Robert W., Canal Lock Design and Construction: The Rideau Canal Experience, 1826-1982, Microfiche Report Series 57, Parks Canada, Ottawa, 1983.

|

Lower Locks at Long Island Lockstation

This is the spot where the sluicing of the Superintendent took place. Photo by Ken Watson, 2007 |

|