The Wall of Water

by Ken W. Watson

It was April 1832 and Daniel Ansley had a problem. His sawmill, located at the outlet of Loughborough Lake, wasn’t working as it should. The fluctuating levels of water in the lake meant that, more often than not, there wasn’t a sufficient head of water to keep his water wheel turning. The mill, which Daniel and his father Amos had built here in 1816, was getting old and repairs had reduced the efficiency of the water wheel and milling machinery. During spring runoff there was lots of water and no problems, his sawmill was able to operate at full capacity. But dropping levels meant that soon there wouldn’t be enough water to turn the wheel and power the saws. He needed to impound more water. His father Amos had passed away in 1830, so Daniel was on his own to run the mill, and now, to come up with a solution to improving his water supply.

|

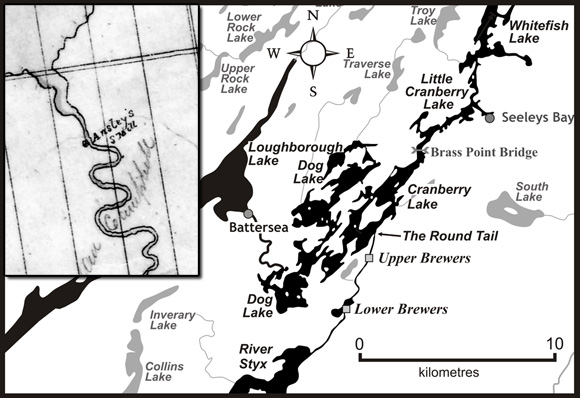

| In this map we can see the location of Battersea on the southeast side of Loughborough Lake. The inset map is from a pre-1832 map showing Ansley’s Mill at the same location. Prior to a mill dam being erected at Morton (just northeast of Whitefish Lake), Loughborough Lake and a much smaller Dog Lake were the main headwaters for the Cataraqui River, which flowed through Upper Brewers. The much larger expanses of water today (a much expanded Dog Lake, an expanded Cranberry Lake and a new Whitefish Lake) are the result of flooding by canal dams at Upper Brewers and Morton. But, even today, water that flows from Loughborough Lake through Battersea still goes to Upper Brewers. Inset map: “Plan of the Township of Pittsburgh Midland District Province of Upper Canada” by Thomas Burrowes, n.d., Library and Archives Canada, NMC 14280. Map by Ken W. Watson. |

As Daniel was pondering a solution, Lt. Colonel John By was preparing for his inaugural trip through the newly completed Rideau Canal. Finishing touches were still being done, but now, with the ice about to break, it was almost time for the first triumphant cruise. The trip was originally going to be done with Robert Drummond’s brand new 110 foot long steamship, the John By. According to the design, it was supposed to draw only 3.5 feet of water, but, when launched, it drew over 6 feet of water, too deep a draught to travel the Rideau Canal. However, Drummond was a resourceful man and he assured Colonel By that a vessel would be ready by mid-May for the big trip. Drummond’s 80 foot long vessel Pumper, which Drummond had used to pump water from behind the cofferdam at the lower lock at Kingston Mills, was in fact a steamship. Its 12 hp steam engine, powering the two side paddles, could move the boat along at a reasonable clip. Drummond quickly had it re-fitted to accommodate passengers, even temporarily renaming it Rideau, a more fitting name for this historic voyage.

Daniel stared at his timber mill dam for the umpteenth time. Two possible solutions, to re-build the mill dam higher, or to locate the mill further downstream, were huge undertakings. He needed a quick solution – the ice was about to break and spring runoff would be raising the level of the lake. Then inspiration struck. It was a technique he had heard about, the addition of flash boards. These were horizontal planks, placed upright on the top of the dam to increase the height of the dam. He could do the work on his own – it wouldn’t take long.

Robert Drummond prepared Rideau for the inaugural voyage. He filled it with supplies for the journey and outfitted the cabin for the comfort of Colonel By, his wife Esther By and their two daughters, Esther and Harriet. Drummond even managed to mount a small cannon to the front the vessel – this would be used to announce Colonel By’s arrival at each lockstation and community on the voyage to Bytown. It would be a grand trip.

Back at Loughborough Lake, Daniel was busy implementing his plan. He pounded upright timbers into the top of his dam, securing them with timber back bracing. Then, taking discarded planks and slabs from his mill, he fastened these against the timber uprights. From the dam’s location (present day Battersea), Loughborough Lake stretched 5 miles (8 km) north and 11 miles (17 km) south. Every foot of water that would rise against these boards represented millions of gallons of extra water, enough to run his mill for weeks. He repositioned his flume to take full advantage of the greater head of water. The job done, Daniel sat back and waited for the water to rise.

It was May 22, and with great fanfare, Colonel By and family boarded the steamboat Rideau (aka Pumper). With a full head of steam, side paddles churning, it left Kingston Harbour and started up the Cataraqui River. The Rideau had been preceeded by the dockyard cutter Snake with two barges, including one containing the band of the 66th Regiment. After locking through Kingston Mills and Lower Brewers, the entire procession passed through the locks at Upper Brewers, through the rocky constriction at the Round Tail and into Cranberry Lake. The lake was, to coin Colonel By, a “fine sheet of still water,” at full navigation depth due to the canal dams at Upper Brewers and at White Fish Falls (Morton). A cofferdam was still present in front of the weir at Upper Brewers – the final touches were being put on the weir to make it fully operational.

As Colonel By’s flotilla passed into Cranberry Lake, some 4 miles (6 km) as the crow flies to the west Ansley’s temporary dam additions started to creak rather ominously. The dam’s location was at the eastern outlet of Loughborough Lake, a headwater of the Cataraqui River. The outflow from the dam went by a meandering creek into a much expanded Dog Lake and then into an expanded Cranberry Lake, the original channel of the Cataraqui River now drowned beneath waters raised by the canal dams at Upper Brewers and Morton. The flotilla continued north. The Snake and the barges would only go as far as Jones Falls before returning to Kingston. The Rideau would continue triumphantly to Bytown, marking the official opening of the Rideau Canal.

Daniel was getting worried, his flash boards were taking a lot of pressure since Loughborough Lake had risen an additional two feet. He could see the uprights supporting the boards starting to bend back – leaks were starting to appear. He opened the flume up to full capacity, yet still the lake continued to rise, putting more pressure on the additions to the dam. He realized the dam was in a dangerous state but he didn’t dare risk going out on top of it to try to reinforce it. He considered taking a boat to the northern outlet of the lake to remove the dam he’d erected there several years ago to block that outflow. But it was of solid construction, it would be very difficult to take apart. It didn’t matter, it was already too late, no course of action would prevent the coming event.

It was a lovely morning at Upper Brewers. The construction crews had been given the day off a couple of days before to view and cheer Colonel By and the procession of boats that passed though the locks. But now it was back to work as normal, putting the finishing touches on the site. Some of the iron work on the locks had cracked during this first passage and that had to be repaired. But more importantly, the weir had to be completed. A cofferdam in front of the weir kept it clear of water as the stop log lifting mechanisms were put into place. The work was almost done.

|

In this 1975 air photo of Upper Brewers (looking south) we can see the configuration that was present in 1832. The Cataraqui River flows from Cranberry Lake to the dam and weir that block the original channel of the river. The sections labelled Canal Cut and Basin are an artificial bypass, the cut blasted through a bedrock ridge, the basin formed by embankments on either side. Two locks lead boats down to the level of the river below. The canal dam and weir have raised the level of the river by about 18 feet in front of it. The powerhouse behind the dam is a new (1939) addition. The Lockmaster's house (built in 1842) sits on a knoll overlooking the dam and locks (just above the words "Canal Cut"). In 1832 this knoll was devoid of trees, cut down to help prevent malaria, and anyone standing on the top had a tremendous view of both the locks and the approaches to the locks.

"Upper Brewers Mills," October 1975, Parks Canada, Ontario Service Centre

|

The foreman on the job was standing on the canal dam, watching his men work on the weir. He wiped his brow and looked up channel. It was a clear, calm day – but now he heard a strange sound – like a distant rushing wind. He’d never heard anything quite like it. The sound seemed to be coming from the north, but he couldn’t place it. The view up channel didn’t seem quite right, but it took a few moments for his brain to process exactly what he was seeing. His eyes widened as he realized he was looking at a wall of rushing water.

“Run!” he cried, turning to the men working on the weir. “Get to high ground!”

The men, used to obeying the foreman’s orders, immediately ran for the hills. Their decision-making was helped by the sight of the foreman, running for all he was worth along the top of the dam towards the knoll that overlooked the locks.

The foreman had scrambled partway up the knoll when he turned to see the first rush of water crash into the cofferdam. For a few seconds he thought it might hold, but then with the screech of splitting timbers, the force of the water carried it away. Water mixed with cofferdam timbers crashed into the weir. Although the main force of the wave was blunted, the water continued to rise and now sloshed its way through the new side channel towards the locks.

The foreman turned and ran to the top of the hill in time to see the floodwaters hit the gates. He gave a sigh of relief as the gates held. But the worry now was the rising water, would it breach the lock itself? Water overflowing a lock would quickly erode out the sides. Although the lock had been built with almost a 4 foot flood guard (the height of the lock wall above normal water level), it wasn’t designed for this type of rapid rise.

For a few minutes it looked like the foreman’s worst fears were about the happen. The water rose to the top rail of the lock gates, about two feet below the elevation of the lock wall, and started to spill into the lock. Then, still rising, it started to flow over the berm beside the basin. There was nothing that could be done. He looked around, everyone was now on high ground. He felt his heart pounding a mile a minute from the recent excitement and his anxiety that the lock might fail.

But now, as he watched, the water level stopped rising. In fact it looked like it was slowly starting to go down. The water flowing over the lock gates slowed to a trickle and then the level dropped below the height of the gates. He ran over to the other side of the knoll and looked down. The open weir, now with cofferdam logs jammed in it, was doing what it was designed to do – carrying away surplus water. Water was roaring through the weir, but the weir structure itself was holding up just fine. It had been designed to accommodate floodwaters and now it was doing just that.

The foreman started a count of his men. In the end no one was hurt, not even a scratch. They had been lucky.

There were only two possible sources for the floodwaters – a canal dam breach at Jones Falls, unlikely since that solidly constructed stone dam had been completed the previous fall, or a mill dam breach at Ansley’s Mills. By noon the water levels had stabilized enough that he could send men in canoes to investigate both possibilities. A few hours later he got word back that it was the Ansley mill dam that had failed. He wrote up a report of the incident and sent it by canoe directly to Bytown. His boss, Robert Drummond and the supervising Royal Engineer, Lieutenant Briscoe, were both with Colonel By on the inaugural voyage aboard the Rideau. At the time of this incident, the Rideau was still steaming towards Bytown, it arrived there on May 29, about the same time as the report of the incident at Upper Brewers caught up with it.

Daniel stared at his ruined dam. When the first of the flash boards failed all hell broke loose. The force of the rushing water ripped out the remaining flash boards and opened up a considerable breach in the dam. For a while it looked like all of Loughborough Lake was going to drain to the Cataraqui River. Preoccupied with the ruins of his dam and significant damage to his mill, he didn’t give much thought to the effect all his lost water was having on the brand new Rideau Canal lockstation downstream from his dam.

When Colonel By received word of this incident, he sat down and penned the following letter, dated May 30, 1832, to his commanding officer, Colonel Nicolls:

I have the honor to report for the information of the Master General and Right Hon'ble & Hon'ble Board, that a few days since, a temporary dam broke away which was improperly erected by a private Individual at Ansley's Mills on the South East outlet from Lough'borough Lake, and was formed of rough boards and Slabs, intended to Keep a head of Water on the Lake about two feet higher than the original Saw Mill Dam - this Lake contains from 16 to 18 Square Miles, and is about 19 feet above the level of the Rideau Lake - consequently, when this temporary Dam gave way, the whole of the water, so raised, rushed into Cranberry Marsh, and caused a greater pressure on the embankments and Gates at Brewers Upper Mills, than could have been anticipated, but, fortunately, did little or no injury, except that of carrying away the Coffer Dam in front of the Works at Brewers Upper Mills. To prevent the damage that might arise to the Works by the recurrence of a similar accident, I have taken upon myself the responsibility of directing that a safety Gate be constructed at Brewers Upper Mills, agreeably to the Enclosed Plan, the expense of which shall, be reported as soon as ascertained, and I trust that the whole of the Canal will again be open to the public in the course of 18 or 20 days.

This delay affords me an opportunity of replacing such Iron Work as had given way on first passing a Steam Boat from Kingston to the Ottawa, and points out the necessity of vesting in the Officers Commanding on the Rideau Canal the control of all waters above the level of the Rideau Lake, whose duty it should be to inspect all Mills Dams erected by private individuals in such situations as their failure would create injury to the Works, and have authority to cause their being strengthened, if found necessary - to prevent the navigation from being at any time interrupted. (Price, pp.299-300).

Presumably By had already given some thought to the idea of a safety gate, his enclosed diagram was designed for emplacement in the rocky constriction just upstream of the basin at Upper Brewers. This gate would lie flat on the bottom of the channel and then either be raised manually or swing up with high water flow such as a flood. Once upright it would block the channel. It was one of only two installed on the Rideau Canal, the other being at Newboro, placed there for a slightly different reason, to prevent Upper Rideau Lake from draining through the canal cut should the Newboro Lock fail.

|

Lt. Colonel John By's design for a safety gate at Upper Brewers.In his notes on the diagram By states "The gate will have 7 feet of water laying over it when laying in a horizontal position, and will be kept at rest by being loaded with Chains fastened to the head of the heel post and laid in the corners of the gate marked A until the said chains are lifted up when the buoyancy of the gate with a trifling assistance will raise it into its place between the Piers and prevent any rush of water."

"Plan of the Safety Gate building at Brewer's Upper Mills" by John By, May 30, 1832 - National Archives of Canada, NMC 3218 |

As for poor Daniel and his dam, it is unknown if it was reconstructed. A few years later, in about 1840, Henry Van Luven registered a deed on the land occupied by Ansley’s mill. By about 1848 he had laid out lots as the foundation for a town which he planned to call Rockville. When Crown mill sites became available for purchase in 1857, Van Luven bought the rights. The name Rockville was turned down by the postal inspector and a new name, Battersea, was chosen for the community. Van Luven erected a new mill on the site at that time.

The Rideau Canal works were never flooded again, although battles between the Rideau Canal and millers continued for decades, mostly on topics such as the availability of water for milling (often in competition for water needed for navigation) and the discharge of debris, notably sawdust, by the mills into the Rideau Canal.

The safety gate at Upper Brewers never saw use and it was removed in late 1847 with the supporting piers removed the following year.

Behind the story

This story is based mostly on the facts stated in Colonel By’s letter of May 30, 1832. The use of flash boards on the dam is an assumption based on By’s statement that the temporary dam was built of “rough boards and Slabs” intended to keep the water about 2 feet higher than the original mill dam. The most common mill dam of the period was the simple log dam, built by putting long logs at an angle into the upstream flow (see diagram below and on next page). The force of water against the angled front actually helps to lock the dam in place. A problem with this type of dam is that, to be structurally strong, the angle has to be kept low and therefore the maximum height of the dam is determined by this angle and the length of the logs available for use.

|

Log Mill Dam and Canal Dam at Davis Lock.

The log dam on the left is the actual mill dam used by Walter Davis Jr. for his sawmill. Built in about 1820, it was about 150 feet long and 10 feet high and during the lock construction, it served as a coffer dam for the erection of the  canal dam (which exists today at Davis Lock), shown on the right. The flat top on the log dam was a temporary bridge of planks added by the contractor, Robert Drummond. canal dam (which exists today at Davis Lock), shown on the right. The flat top on the log dam was a temporary bridge of planks added by the contractor, Robert Drummond.

The diagram on the right shows another log mill dam. In both cases, the sloping side faced upstream.

Top = “Rough Plan of the Lock, Dam &c. at Davis' Mill” by Thomas Burrowes, n.d. (c.1830), National Archives of Canada, NMC 130287

Bottom = Illustration from "Rideau Dams", by Lieutenant W. Denison, in "Papers on Subjects Connected with the Duties of the Corps of Royal Engineers", London, vol. 2, 1838. |

|

Two Types of Mill Dams

These two diagrams show different types of mill dams, the top being a log dam as described above, the lower being a plank and timber dam. The lower image does convey what flash boards at the top of a log dam might have looked like (a plank dam erected on top of a log dam).

From "The Construction of Mill Dams" by James Leffel & Co, Springfield, Ohio, 1874 (top = p.23, bottom = p.54) |

Flash boards, still in use today, are a simple measure to impound a bit of extra water. They are erected on top of the dam. Since they are at the top, they aren’t subject to the same amount of hydraulic pressure as the lower parts of the dam. But the weight of water is no trivial matter, and to be successful, proper bracing and strong material must be used. Colonel By’s comments about rough boards and slabs indicate that Ansley was using sawmill scraps and clearly, however he constructed a temporary dam to hold back extra water, it wasn’t of sufficient strength and it broke under the weight of the water.

A fear of any canal builder is that a lock will be overflowed. On the Rideau it wasn’t so much the possibility of dam failure as it was spring flooding that was the main excess water worry. The problem with flooding is that a lock is in essence a dam. In a Rideau lock, a layer of clay behind the stonework (in some cases today replaced by concrete or reinforced with grout) forms the impermeable barrier. If a lock gets overflowed, the turbulence of the water can quickly start to erode this impermeable material behind the stonework and eventually wash away the entire lock. There are several design features used in the building of the Rideau Canal to prevent this from ever happening.

One key flood protection feature is the flood guard, which is the height of the stonework, on the upstream side, above the normal water level. Go to any Rideau lock today and you can see this for yourself. The “head lock” (upstream lock) at most lockstations (all stations that are in an uncontrolled environment such as a river or lake) will have the stonework a few feet above the normal water level. With other locks, such as the internal locks in a flight of locks, the stonework is just a few inches above the normal water level since the water level can be well controlled. The extra elevation of the stonework on the head lock is designed to accommodate the rise of water during normal spring flood.

The second flood protection feature is the design of the lock gate. If you look at a Rideau lock gate, you’ll notice that the top rail of the solid section of the gate is actually a couple of feet below the height of the stonework. This means that as water rises against the lock, the first thing that will happen is that it will flow into (rather than over) the lock and out the other end. The lock will start acting as a by-wash and in cases of minor flooding, this will allow the lock to pass sufficient water to prevent overflowing, without doing any damage to the lock.

Another flood protection feature is found at some locations, such as Upper Brewers, where the man-made berm (embankment) that helps to impound the water above the lock is slightly lower than the stonework of the lock. So, like the gate, water will start to flow over the berm, rather than over the lock. You might lose that section of the canal, but it is much easier to reconstruct a berm than it is a lock.

Of course the main flood control feature is the weir. Originally all of the dams on the Rideau were designed as overflow dams, but once Colonel By saw the Rideau and Cataraqui rivers in full spring flood, he quickly re-evaluated his plans and added a weir at each lockstation. The heights of most of the dams (with a few exceptions such as Clowes, Nicholsons and Black Rapids) were raised to turn them into non-overflow dams. The weir serves as a water level manager, stop logs are either added or removed from the weir to increase or decrease flow. The weir is used in late winter to draw down the bodies of water ahead of the locks. This provides reservoir capacity for the spring melt, meaning that all that excess water doesn’t have to be passed through the system all at once (which would cause a flood and potentially overflow a lock).

In terms of the title of this story, could there really have been a “wall of water?” Possibly, depending on how fast the water rushed out of Loughborough Lake. As Cranberry Lake started to fill up with this outflow, the constriction at the Round Tail, the narrow entrance to the Cataraqui River above Upper Brewers, would have forced the floodwater higher and faster, similar to a tidal bore. We know that the flood washed away a cofferdam. This would have required a lot of force.

This is one of the few places on the Rideau where such an event could have happened. Once the canal was built, millers on the Rideau Canal itself used water that was controlled by canal staff. For instance, at Merrickville the canal dam and weir were upstream of William Mirick’s mill dam, so even if his mill dam broke, the canal dam and weir would prevent any flooding. Of course if the canal weir broke (and some did) then flooding could happen.

There were only a few other dams placed in the upstream reaches of the Rideau. For instance, there was Drummond’s dam at the outlet of Hart Lake, Stoddard’s and Manhard’s dam at the outlet of Westport Sand Lake, Clothier’s dam on Kemptville Creek, and by the mid-1800s, Tett’s and Chaffey’s dam at the outlet of Devil Lake. But none of these impounded the amount of water that Ansley’s dam at the southeast outlet of Loughborough Lake did and thus never posed the same level of risk.

Sources:

Battersea Women’s Institute, Tweedsmuir History, n.d.

Leffel, James & Co., “The Construction of Mill Dams,” James Leffel & Co, Springfield, Ohio, 1874.

Moore, Jonathan, “Rideau Canal National Historic Site of Canada: Submerged Cultural Resource Inventory,” Underwater Archaeological Services, Parks Canada, Ottawa, April 2005.

Rayburn, Alan, Place Names of Ontario, University of Toronto Press, 1997.

Patterson, William J., Lilacs and Limestone, An Illustrated History of Pittsburgh Township, 1787-1987, Pittsburgh Historical Society, 1989.

|