Lt. Gershom French’s 1783 Survey

We now jump to 1783, a milestone year for the Rideau Region. The Second Treaty of Paris, a peace treaty between the British government and the American revolutionary government, had just been signed. Since the treaty placed several British military bases inside the U.S., the British decided to create a new base at Cataraqui, later to be known as Kingston. In 1673 the French had established a small post in this location, later known as Fort Frontenac. It was captured by the British in 1758, but not occupied. Now, in 1783, Governor Haldimand ordered Major John Ross, the commander of Fort Oswego, to investigate the area around Cataraqui. Ross started the construction of a new base and also travelled part way up the Cataraqui River, discovering a good source of water power at Cataraqui Falls, and recommending that a sawmill be constructed in that location. It was the dam for this sawmill that was to create the first man-made alteration of the Rideau, flooding part of the Cataraqui River.

This year also marked another significant milestone, the first survey of the Rideau. This task was given to Lieutenant Gershom French, an Assistant Engineer with the Corps of Loyal Rangers (also known as “Jessup’s Corps”). Born in 1753 in Southbury, Connecticut, Gershom was a signatory to the Lansingburgh Declaration of Independence in May of 1775. He advocated peaceful change and when it became evident that the revolutionaries advocated violent means, he became a Loyalist. He served with the Prince of Wales American Volunteers in 1776 and by October 1777 had joined the Queen's York Rangers, commanded by Lieut. Col. John Peters, as Lieutenant and Adjutant. This unit was amalgamated in 1781 with the King’s Loyal Americans under Major Edward Jessup and was called the Corps of Loyal Rangers.

In 1783 French was ordered to explore the Rideau Route, known to the British as a native travel way connecting the Ottawa River with the St. Lawrence River. He organized his party in Montreal and embarked on his journey in two birch bark canoes with “seven men of the Provincials, Two Canadians and an Indian as Guide.” The Provincials were men of the Provincial Corps of the British Army and the Canadians were French Canadians. The aboriginal guide was key since they were exploring a route not previously surveyed by Europeans, but one that had been use for millennia as an aboriginal travel way.

| |

|

| |

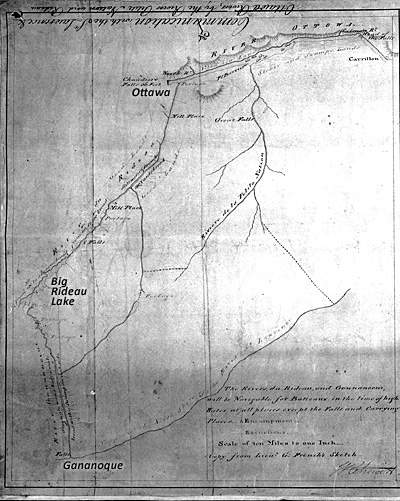

Lt. French's 1783 Survey Map

This first map of the Rideau is a very simple representation of the waterway. The left side of the map shows the Rideau River to Rideau Lake (labelled River du Rideau) and then shows an almost straight line from there south to present day Gananoque (the names Ottawa, Big Rideau Lake and Gananoque are my annotations to the map).

“Communication with the St. Lawrence & Ottawa Rivers, by the Rivers Petite Nation and Rideau” copied from sketches by Lt. Gershom French 1783, by William Chewitt, August 26, 1794, Archives of Ontario, AO1336 (left panel).

|

Lt. French prefaces his survey journal with “Proceedings in Exploring the Lands on the Ottawa River from Carillon to the Rideau, and from the mouth of the River to its Source, from thence to the River Gananoucoui and down the same to the Fall into the St. Lawrence about five Leagues North East from Cataraqui.” This succinctly describes his survey, from Carillon [east of Hawkesbury] on the Ottawa River, to the Rideau River, up that river to Rideau Lake, portaging over the Isthmus to Newboro Lake, down those lakes to Jones Falls and the White Fish River, down that river to Lower Beverley Lake and from there to the Gananoque River coming out at the St. Lawrence River at present day Gananoque. This was the route his aboriginal guide led him, the main canoe route between the St. Lawrence and Ottawa rivers.

Lt. French wasn’t looking at the waterway for navigation, he was looking at it in terms of its adjacent lands and their potential for settlement. In that regard, every few kilometres, he would send a party of men inland for a distance of about 5 km. They would blaze a line, check out the character of the land, and return to the canoes. His journal entry for their first survey above Rideau Falls states:

“The banks of the River in general raise about twelve feet above the high water from thence the land continues very Level, it is a Dark Soil from 7 to 10 Inches Deep, with a Sandy Loam below, clear of Rocks and Stones, Timbered with Maple, Beech, Birch, Elm, Butternutt &c. with an Edging of Cedar and Pine always covering the Banks of the River and wherever the water is Rapid, the Shores are Lined with Lime-Stones, in the Route there were two excursions made one each side [of] the River to the distance of a league in which myself and party found the land Everywhere good.”

In his explorations of the Rideau River he found the lands to be generally good, but this changes when he crossed over into the rocky terrain of the Frontenac Axis where he found “The Lands laying in the Route is Intirely too rocky to Cultivate, the Timber is Pine, Cedar and Mountain Oak, the whole bad of its kind. At the Carrying Places mentioned are good Mill places.”

It is interesting to note on French’s map and journal that there are very few portages (“carrying places”) noted. This is in part because surveyors and voyageurs of the day would haul or line their canoes up and down rapids where they could rather than unloading the canoes and carrying them around a navigation impediment. Only at places with rushing rapids constrained by rocky walls (i.e. Jones Falls) or actual waterfalls (i.e. Merrickville) was a portage noted.

|