Note: this page contains two articles. The first, The Military Roots of the Rideau Canal, looks at the reasons the Rideau Canal was built and its on-going military role in the 19th century. The second article, Elements of the Rideau Canal's Military Heritage, looks at military structures that can be seen today on the Rideau Canal and also military structures that have been lost over time.

The Military Roots of the Rideau Canal

by

Ken W. Watson

Note: This article first appeared in the Winter/Spring 2012 edition of Rideau Reflections, the newsletter of the Friends of the Rideau (www.rideaufriends.com).

Two hundred years ago, the United States declared war on Great Britain, starting what is today known as the War of 1812. One of the results of that war was the Rideau Canal and we can still see many elements of its military roots today.

|

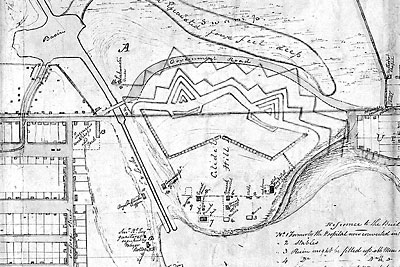

Fort Ottawa?

The angular lines on this 1838 map represent the outline of a fort on what is today, Parliament Hill. Back in 1838 it was known as Barrack Hill, but has been renamed “Citadel Hill” on this map. It was drawn by John Burrows and signed by Major Bolton, then Superintending Engineer for the Rideau Canal. Versions of this map showing the same outlines of the fort date back to one signed by Lt. Colonel John By in 1831.

Section from "Plan of By Town Shewing the Proposed Fortifications, Land taken from Mr. Sparks, Lot No. C in Conn. C., Also Crown Reserve O", by John Burrows, 1838, Library and Archives Canada, NMC 18913.

|

There were several reasons why the U.S. declared war on Britain. One of the most cited was the British tactic of “pressing” naturalized U.S. citizens into the British Navy. Napoleon was busy trying to expand the French empire and so war was raging between Britain and France. Britain placed a trade embargo on France and was checking all ships leaving from the U.S. If any former British citizens were found on-board (many of these were British Army or navy deserters), they were taken and made part of the British Navy. Britain considered them to be British citizens while the U.S. considered them to be U.S. citizens. This and other issues rose to a boiling point and on June 19, 1812, U.S. President Madison declared war on Great Britain.

The War of 1812 was a rather convoluted affair. The players in Canada included small parts of the British Army and British Navy (since most of those forces were busy in Europe fighting Napoleon), Canadian militia units and several groups of First Nations. Battles and skirmishes went back and forth, Canada winning some, the U.S. winning some. A peace treaty between the U.S. and Britain was signed on December 24, 1814. The last major battle, the Battle of New Orleans, was fought in January 1815, since news of the peace treaty had not yet arrived in North America. General Prevost (in charge of Canadian forces) was officially informed of the peace treaty on March 1, 1815.

In the end, borders remained unchanged but the war left several lasting legacies in Canada. One was a heightened sense of Canadian identity. Another was a lingering worry of American expansionism and of the loyalties of Americans living in Canada. But the one that ultimately led to the building of the Rideau Canal was the vulnerability of the naval harbour at Kingston.

Kingston was a key military and naval base for Canada. Its location at the foot of Lake Ontario and the head of the St. Lawrence River made it strategically important. But it also made it vulnerable. The U.S. equivalent to Kingston at the time was Sackets Harbor (located on Lake Ontario just west of Watertown, NY), a U.S. naval base and military staging point. Ships stationed there made several attempts on Kingston during the War of 1812. Getting supplies (material and men) to Kingston involved either traveling over very difficult land routes (very crude roads) or by boat up the St. Lawrence River, the south side of which was the United States. After several engagements on the St. Lawrence during the War of 1812, it was clear that it wasn’t a safe route.

So, immediately after the war, the British military looked at ways to fix these vulnerabilities. Key to this was developing a safe military supply route to Kingston, utilizing what was known as the Rideau Route, first surveyed in 1783. In 1816, the route was mapped from a military point of view by Lt. Joshua Jebb of the Royal Engineers. However, with war chests depleted from the protracted Napoleonic wars, the British had no immediate desire to fund a canal project on the scale of the Rideau Canal in Canada.

The person who got the Rideau Canal project off the ground was Arthur Wellesley, better known as the Duke of Wellington (aka the “Iron Duke”). He featured prominently as a general in the Napoleonic wars, rising to the rank of Field Marshall in 1813 and becoming a duke in 1814. In 1819 he was appointed Master General of Ordnance, a post he held until 1827 (shortly after, in 1828, he became Prime Minister of Britain). Ordnance was in charge of things such as fortifications, transport routes, supplies and engineering. By the time of his appointment as Master General of Ordnance, a military canal project to make the Ottawa River navigable was already underway, initiated by Charles Lennox, the 4th Duke of Richmond. But to complete the safe military supply route to Kingston, the Rideau Canal was needed, and the Duke of Wellington started to lobby to have it built.

There was still no immediate desire to have British coffers fund such a project, the British would have preferred to see Upper Canada finance the canal. In the early 1820s, the Macauley Commission was set up by the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada to investigate inland navigation routes. They looked at the area of today’s Welland Canal, the St. Lawrence River and, in 1823 and 1824, they had surveyor Samuel Clowes do a detailed survey and cost estimate for the Rideau Canal.

Upper Canada legislature’s main concern was commercial trade and they didn’t see any significant commercial potential with a Rideau Canal. A British military commission, set up to look into the details of the Rideau Route, reported back in 1825 that there was no chance that Upper Canada would participate in the Rideau project. The military importance of the Rideau Canal to the defence of Canada remained undiminished and now the decision was made to have it built, funded by the British Treasury.

|

“Yankee” symbols

It is somewhat ironic that due to a shortage of hard currency in Canada, the workers on the Rideau Canal, a canal being built to help defend Canada against the U.S., were paid in American Half-Dollar coins. [image from Wikipedia]

John Mactaggart, Clerk of the Works for the Rideau Canal, noted that “the emblems [liberty and an eagle] on the current coins of Canada [American half-dollar coins] help to make Yankees of the Colonists.” Three Years in Canada, John Mactaggart, 1829.

|

Lt. Colonel John By of the Royal Engineers was appointed Superintending Engineer for the Rideau Canal project in 1826. During the construction of the Rideau Canal, Colonel By never lost sight of the fact that he was building a military canal. He lobbied to have the locks made larger with a specific military purpose in mind - to accommodate the new steam powered gunboats. He originally asked for locks 150 feet long and in June 1828 he got some of what he wanted, with a decision to extend the length of the locks from 108 feet to 134 feet.

As the construction of the locks and dams came to a close in early 1832, Colonel By moved on to his next military need for the Rideau, defensive structures. With a long range goal of having blockhouses at all the lockstations, he initiated construction on five of them. Four and half were completed before orders came down to stop construction - cost overruns had hit the fan of the British Parliament.

The defensive structures that By wanted were outside the original mandate to create a navigable waterway. The four completed blockhouses are those at Kingston Mills, Newboro, Narrows and Merrickville. The half blockhouse was at Burritts Rapids where only the stone first storey was completed before construction was halted.

But this wasn’t to be the end of the Rideau’s military heritage. The next potential threat to the Rideau was the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837-38 which led to a military invasion of Canada by Americans. The rebellion itself was fairly quickly quashed in Canada, but in the U.S. a group known as the Patriot Hunters, whose aim was to “liberate” Canada from the tyranny of British rule, took advantage of the rebellion (and of the rebels who had fled to the U.S.). These were essentially militia units and were not officially sanctioned by the American government. The Hunters felt that if they marched into Canada, the local populace would support them as liberators.

A bit of a fiasco ensued. Some 1,500 Hunters started out in the fall of 1838 with the intent of invading Canada. Numbers dwindled until only about 300 ended up trying to capture Prescott, Ontario. The presence of a British gunboat kept them from their intended target and instead they holed up in a very large stone windmill located on the shore of the St. Lawrence River, just north of Prescott.

The Battle of the Windmill, which lasted from November 12 to 16, 1838, allows for a point of fact to be made about the Rideau Canal and its role in the military defence of Canada. It has been, and still is, said that the Rideau Canal never served its original military purpose. That is incorrect, it did in fact serve a military role.

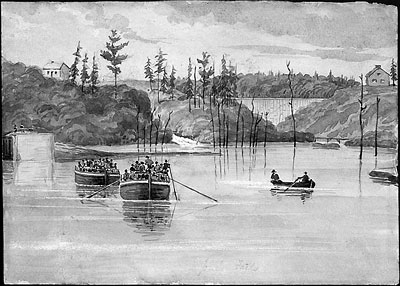

In the Fall 2008 issue of Rideau Reflections, Bob Sneyd provided an excellent article outlining the military deterrence role of the Rideau Canal (see Rideau Canal: Endurance Of Its Military Rationale, 1812-1871). But perhaps more tangible is the fact that the Rideau did serve as a military travel way for troops who battled invading Americans. Those troops were Royal Marines who used the Rideau Canal to get to Kingston in June of 1838. They took part in the Battle of the Windmill, with one being killed and several injured. That’s a well documented example, but other troops and supplies used in the battle also travelled via the Rideau Canal. So it was in fact used as a military travel way.

|

Royal Marines at Jones Falls in 1838

A company of Royal Marines on their way to Kingston pass through Jones Falls on June 28, 1838.

“Jones Falls, Rideau Canal, Upper Canada” by Philip John Bainbrigge, 1838, Library and Archives Canada, C-011835.

|

The Upper Canada rebellion sparked renewed worry about the vulnerability of lockstations and orders immediately came down in 1838 to built wooden guardhouses in two critical spots - at Jones Falls and at the Whitefish [Morton] dam. Over time, more substantial stone defensible lockmaster houses were erected at most of the lockstations [see the Elements of the Rideau Canal’s Military Heritage article in this newsletter].

The rebellion also sparked the bit of military doodling shown at the beginning of this article, the outline of a fort parked on top of Parliament Hill. The outlines of that fort are shown on maps dating back to at least 1831. We see similar outlines of a fort on an 1829 map of Kingston Mills. That map has a note on it written by Col. Durnford (Commander of the Royal Engineers in Canada) saying “Kingston Mills showing Works projected for the defence of the Entrance to the Rideau Canal.” It’s unknown if the plan for that fort was dusted off in 1838.

Tensions between Canada and the U.S. rose again during the Oregon Crisis of 1844 when the new Democrat President of the U.S., James Polk, asserted that most of the area that is now southern British Columbia belonged to the U.S. Boundary negotiations between the U.S. and Britain broke down and American expansionist voices grew louder. Canadian military leaders once again voiced the wisdom of building the Rideau Canal, providing them with a safe military supply route to Kingston. Military plans for Upper Canada had the St. Lawrence as the first line of defence, with sections of the Rideau Canal as the second line. Military command of the Rideau would be established in the Merrickville Blockhouse.

By 1856, we were on reasonably good terms with the U.S. and most military worries had ceased. The Rideau Canal was handed over from military control to civilian control that year with the transfer of ownership of the canal from Britain to Upper Canada.

The U.S. Civil War saw U.S./Canada relations deteriorate again, coming to a head in 1862 when the Union seized the British ship Trent which was carrying Confederate envoys to Europe. In Merrickville, Lockmaster John Johnson started preparations to vacate the Merrickville Blockhouse thinking it was going to be needed by the military.

That seems to be the last time the Rideau Canal and its fortifications were factored into military planning. The canal had been serving Canada well as a commercial route since it opened in 1832 and it maintained that role going into the 20th century. By the late 1800s it was also starting to transform into a recreational waterway. Today, in addition to its role as a recreational waterway, it serves as a tangible heritage reminder of our past, of Canada’s early nationhood.

The military roots of the canal are still physically evident in the blockhouses and defensible lockmaster’s houses whose roles today are either accommodation and/or interpretation of the Rideau’s rich heritage.

The most recent echo of the War of 1812 on the Rideau Canal was the awarding of World Heritage Status in 2007. One of the criteria used for World Heritage Status was that “the Rideau Canal is an extensive, well preserved and significant example of a canal which was used for a military purpose linked to a significant stage in human history - that of the fight to control the north of the American continent.”

- Ken Watson

|

Fort Kingston Mills?

The angular outlines of a fort appear on this 1829 map of Kingston Mills.

“Plan of the Ground in the vicinity of Kingston - Mills; with sections of the High Lands near the Locks now constructing for the Rideau” by Thomas Burrowes, 1829, Library and Archives Canada, NMC 11389.

|

Elements of the Rideau Canal's Military Heritage

Heritage Preserved

There are many military features along the Rideau Canal today that have been well preserved. This summer, during the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812, will be a good opportunity to get out and visit some of these. They are reminders of the fragility of our early nation.

The most obvious are the four blockhouses: Kingston Mills, Newboro, Narrows and Merrickville. At Kingston Mills the blockhouse is set up as it was in its military heyday. You can see how soldiers/militia lived in this building and all the design features of a blockhouse. The blockhouse at Newboro is mothballed at the moment and the one at Narrows is being used as a lockstation house (but you can still see all the exterior blockhouse features of both).

|

Merrickville Blockhouse

The Merrickville Blockhouse is the largest blockhouse on the Rideau Canal. It sits in a dry moat adjacent to the upper lock.

Photo: Ken W. Watson.

|

The Merrickville Blockhouse, the largest on the Rideau, is located where, back in 1832, a good quality road from the St. Lawrence River met the Rideau Canal. This was the most likely route for invading American armies to travel, so Colonel By wanted a larger blockhouse (although, in the end, not as large as he would have liked). The blockhouse is open during the summer months as a museum operated by the Merrickville and District Historical Society. For more information see www.merrickvillehistory.org

The other visible military features are the defensible lockmaster’s houses with their stone walls and gun slits clearly indicating their purpose for lockstation defence. These were built in response to the Upper Canada rebellion. A key feature of these houses is their location on the landscape. When originally constructed (with the lockstations mostly treeless), most of these houses provide a view to both approaches of the lock. The military advantage of this is obvious, to clearly see the enemy, but it also served the locksmasters extremely well, providing a clear view of approaching vessels.

Look for these houses at the lockstations this summer. See how some, such as Sweeney House at Jones Falls and the defensible lockmaster’s house at Davis Lock, have been restored to their original appearance. Others show some of the alterations done by their occupants, added extensions and in several cases a second storey, all to make them more liveable. The Lockmaster’s House Museum at Chaffeys Lock is in such a 2-storey building.

Have fun this summer exploring these physical reminders of the Rideau’s military heritage.

Heritage Lost

|

Whitefish Dam Guardhouse

This c.1895 photo shows the guardhouse sitting high on top of the cliff overlooking the dam.

Photo: Parks Canada, Harold Nichol collection.

|

Not all the military structures on the Rideau Canal have stood the test of time. Two that go back to the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837-38 are the wooden guardhouses that were built at Jones Falls and at the Whitefish [Morton] Dam.

In July 1838, militia units were stationed at several spots on the Rideau Canal, including at Jones Falls and the Whitefish Dam. A problem at both places, particularly Whitefish, was accommodation.

In the fall of 1838, construction started on two wooden guardhouses, 20.5 feet by 22.5 feet in size, built using large cedar timbers. They were designed to accommodate 14 men (13 privates and 1 sergeant).

The guardhouse at Jones Falls was ready for occupation in January 1839, the one at Whitefish a bit later. Militia occupied these two buildings until 1843 after which a single guard occupied the Whitefish Guardhouse until 1856.

With the transfer of the Rideau to civilian control, military use of the guardhouses ceased. The one at Whitefish was rented out from time to time. In 1871, at Jones Falls, incoming Lockmaster Henry Layng lived for 10 months in the guardhouse while waiting for outgoing lockmaster, Peter Sweeney (who was living in the stone defensible lockmaster’s house), to find a place to live.

The Whitefish guardhouse didn’t receive any maintenance. By 1900 it was only being used as a picnic spot by passing tourists and was starting to fall apart. In 1929 it was deemed a public hazard and torn down.

The guardhouse at Jones Fall initially fared a bit better, receiving some maintenance since it was a useful building at the lockstation. By the early 1930s there was some recognition of the historic importance of the building and more maintenance was performed. However, in 1939 it was determined by the government that it did not meet the criteria for a national historic resource and the building was torn down.

- Ken Watson

|